One man’s mission to uncover a WWII decryption machine

Randell’s book, The Origins of Digital Computers, Selected Papers, was published in 1973. The book included a two-page summary by Michie of Randell’s findings about Turing.

At this point, Randell felt this was as far as he could go in telling the world about Colossus and he stopped searching until 1975. A number of books were published in 1975, but Randell said the true relevance of Colossus remained a secret. “This emboldened me to raise the issue of clearance again,” said Randell. He then approached Leonard Hooper, ex-director of GCHQ, who was at that point working in the Cabinet Office.

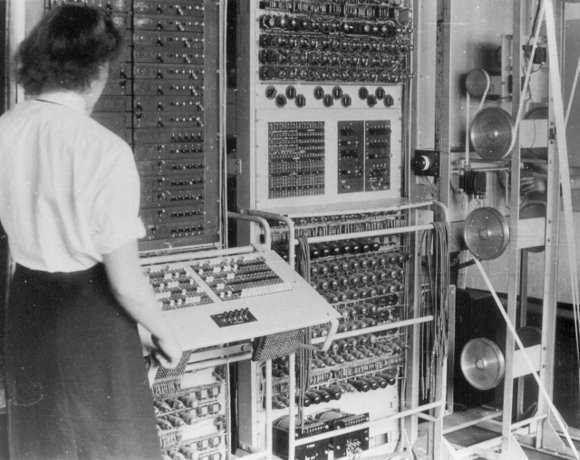

“I was invited to a discussion in July 1975 in the Cabinet Office with Sir Leonard,” he said. “I was ushered into a room to meet him and Dr Ralph Benjamin, GCHQ chief scientist. “They showed me photographs of Colossus [see above] and I was told they were to be released to the Public Record Office. I was also shown a caption to the set of photographs and asked for my advice.”

This was the point when Randell first saw the machine he had been chasing for so long. Randell was then authorised to interview the Colossus team and to publish papers, once the drafts had been cleared by the government. He started interviewing ex-Bletchley workers. This was a challenge, as Bletchley was so fragmented and the workers were bound by tight secrecy and security. “They never discussed work in the cafeteria. Few knew what happened outside their own small group,” he said.

There were no diaries or paperwork and, it now being 30 years after the war, the interviewees found it difficult to recall all the events. “Even establishing a chronology was very difficult,” said Randell.

He taped and transcribed interviews with Tommy Flowers, Bill Chandler, Sidney Broadhurst, ‘Doc’ Coombs, Max Newman, Donald Michie, Jack Good and David Kahn.

After much to-ing and fro-ing with the Cabinet Office, Randell finally got clearance for his paper on Colossus to be released in time for the 1976 Los Alamos Conference. “I was asked not to imply that Colossus was built for code breaking,” he said. So the paper, entitled Computing and Laboratory, did not state the main purpose of the Colossus machine. A year later in 1977, the BBC’s Secret War TV series identified Colossus as a code breaker. Randell replied to the prime minister’s letter pleading that a report about the Colossus should be made in living memory, even if it had to be classified indefinitely. Colossus was eventually declassified in 2003.