What is government as a platform and how do we achieve it?

There are lots of discussion going on at the moment about digital “platforms”, and the impact they might have on UK public services

There are lots of discussion going on at the moment about digital “platforms”, and the impact they might have on UK public services. A rough and ready calculation suggests such an approach could save the UK £35bn each year – but the jury is still out on how best to go about making it happen.

An important question to consider is how the UK IT community can enlist digital technologies to bring about a public service model for the 21st, not the 19th century. The danger is that if we get the thinking wrong, we could waste a lot of public money before it starts to become horribly apparent. Let’s examine the principles of what and how to achieve government as a platform (GaaP).

What is digital transformation?

In an environment increasingly filled with buzzwords, it is essential to maintain clarity of thinking about the purpose of “digital”. For me, digital transformation does not mean better online services per se - although these are of course vital, they have a product-centric focus and do not disrupt the business model of the silo in which they reside.

Instead, digital transformation means gradual transition to an underlying business model that exploits ubiquitous web-based infrastructure to enable commonly shared capabilities. This definition would surprise most within government. When the business model of government is progressively based on shared capabilities, enabled by utility technology and web-based infrastructure, we can expect radical disruption of the market, opening up opportunities for innovation and investment by citizens, public, private, and third sectors alike - unleashing unprecedented innovation, efficiency, and savings.

A shared platform for NHS Jobs

NHS Jobs is the NHS online recruitment service: the first and longest-established example of a public digital platform in the UK, which has already generated savings of over £1bn since its launch in 2003.

The secret of NHS Jobs’ success is that it is a platform. Rather than build its own e-recruitment system, the Department of Health (DoH) recognised that it could instead procure a single, nationally-available commodity that would be consumed on a transactional basis by NHS employers throughout the UK. Working with DoH, Methods Consulting persuaded over 500 NHS employers to forego their specific services to make use of this common capability. NHS Jobs is now one of the top four busiest recruitment portals in the UK and the biggest single employer recruitment site in Europe, with at least one unique visit every two seconds, 24 hours a day, and processing over 275,000 job applications per month.

Best of all, because of the power of NHS Jobs as a platform, the site has now become a valuable commodity. When DoH re-tendered NHS Jobs in 2012, potential suppliers were asked to provide the basic platform to the department at near to cost; instead, they competed on the quality of the additional, innovative services they would be able to offer NHS employers and applicants. NHS Jobs is a poster-child for the opportunity government has to use its scale to trigger the development of commodity platforms around common capabilities. These platforms can be so valuable to suppliers that they are happy to provide the essential public service at close to cost – and will compete to find new, innovative ways of serving the public that utterly transform the traditional ways of performing a particular function.

Although utility and legacy technology, and shared web-based infrastructure may be the CTO’s remit – in the UK government’s case, chief technology officer Liam Maxwell - evolving the shared capabilities is the responsibility of the CEO, and the business. This is why locking down the legacy systems by renewing multi-year outsourcing deals is in almost every case a conspicuous failure of public leadership.

The inescapable DNA of a digitally-enabled public service model is a set of clean, agreed, and common capabilities, distilled and evolved from the currently duplicated and siloed functions, processes, roles and even organisations that exist across government.

For central government, the logical steward for these shared capabilities is the Government Digital Service (GDS), which can help to migrate progressive departments/agencies onto common platforms. For example, assessments and calculations for tax and welfare, payments (in and out), case management, and HR are currently replicated in multiple places in the same way that online publishing was conducted prior to the single Gov.uk website. There are enormous opportunities for rationalisation and simplification across government, as the example of NHS Jobs demonstrates (see box, right).

Achieving more of this sort of service model will require a rigorous distinction between “product” – essentially, bespoke services - and shared capabilities, which are far more important for achieving digitally-enabled public service redesign.

Organising principles

Achievement of government as a platform (GaaP) rests on three organising principles:

- Digital business change will be achieved to the extent that, stewarded and supported by GDS, everyone can gradually maximise shared capability (platforms), and minimise departmental “product” (bespoke services). This represents a radical shift in approach.

- The gradual maximisation and consumption of shared capability must therefore be the primary concern and stream of work for all transformation activities across the public sector. Although very important, improving “product” (bespoke services) is a secondary concern – and only when no shared capability is available.

- In addition to persuading people to share capability – a major challenge in itself – the other significant challenge is to optimise the relationship between shared capability and bespoke services within any one existing silo so that things work together. In order to deliver against their operational remit, digitally transformed public organisations will need to draw on a mix of centrally stewarded shared capability and local product or bespoke services.

What these organising principles mean for government

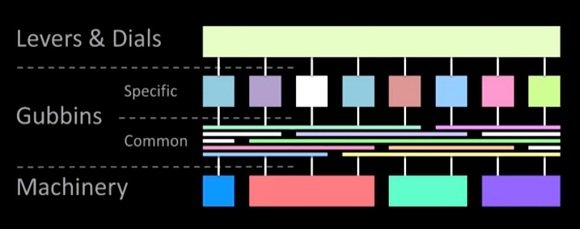

These organising principles are essential to the way in which we need to operate to transition from analogue to digital DNA within government. GDS has already achieved much in driving digital change in government – particularly in securing some quick transformational wins via the25 targeted service exemplars. This is concentrated in the “specific gubbins” area discussed by consultant Mark Foden in Figure 1 – and the video (below) from which it is taken:

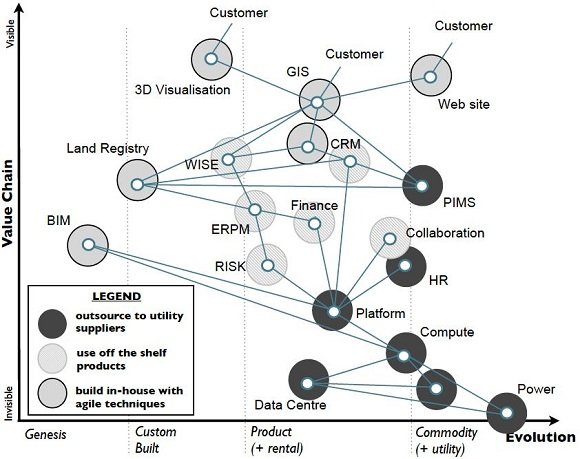

Figure 1: Platform-based view of government (Mark Foden) - see video below:

However, achievement of digital business model change in government requires practical implementation of this GaaP model. Ultimately, this means broadening the focus to establishing “common gubbins”, across not only the digital aspects, but across government organisations too. This requires not only mapping functions and processes across departments and agencies, but identifying where these exist in common across government – as the Gov.uk publishing platform and the Identity Assurance Programme – now known as Verify - have done.

To achieve clarity of purpose, we all therefore need to think very differently about optimising product/bespoke services from how we think about those areas with the potential for shared capability, reflecting Foden’s “gubbins” model. This will enable everybody to apply the correct selection priorities.

Figure 2: Crucial differences between specific vs common digital opportunities

| Product or Capability? | Prioritisation criteria |

|

Bespoke Services

Common Capabilities

|

Quick win, transaction volume, complexity, business impact, automation/savings, contractual constraints

Market maturity, Cross-govt duplication, value chain position, security/DPA, automation/savings |

Pulling principles into a consistent approach and clear methodology

Developing a laser focus on “minimum viable capabilities” (MVC) over and above minimum viable product (MVP) - as shown in Figure 2, above - will require a lot of dialogue within and between public organisations. In particular, we will need to apply consistent clarity of thinking, by rigorously applying the above strong principles to everything we do, if we are to succeed in starting a progressive shift towards enabling cross-government business model change. We will need to communicate the right messages to different stakeholders as we start to build understanding and consensus about shared capabilities, returning to first principles of desired outcomes - asking: “how could this best be done?”, rather than “how is it being done today?”

To ensure clarity, consistency, and defensibility, it’s essential to explain the why as well as the how:

- Explaining the “why” - Building understanding and agreement around a clear definition of digital business; and explaining the importance of identifying shared capabilities to evolve platforms (as above).

- Showing the “how” - Addressing the concerns of stakeholders as the radical implications of consuming shared capabilities becomes more apparent; showing groups of stakeholders how to use a consistent mapping methodology to convert existing siloed businesses into “digital profiles”, showing bespoke, shared, and commodity capabilities in the same way, thus revealing hidden commonality.

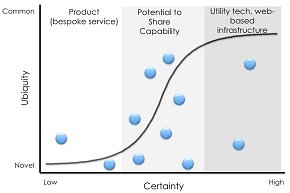

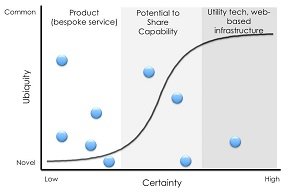

Developing digital profiles

We need to ensure maximum re-use of common platform components by mapping needs consistently against whether they are innovative and unique to government and therefore likely to be bespoke (MVP), candidates for shared capability within government (MVC), or commodities (products or services that can be procured or consumed straight from the open market). This will encourage the evolution of a service architecture that is based on a service-oriented view, supports an ecosystem of providers around a core set of capabilities, and opens up access to a broad community through standard interfaces.

This approach is based on Simon Wardley’s work, extended to enable a clear distinction between “product” and “capability” from which we then derive a simple methodology for achieving government as a platform.

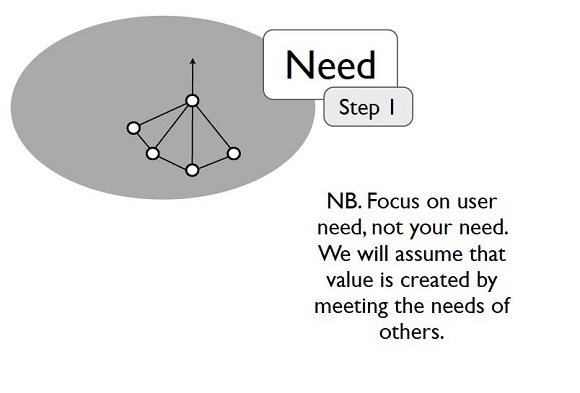

Step one: User need

We need to identify the end requirement:

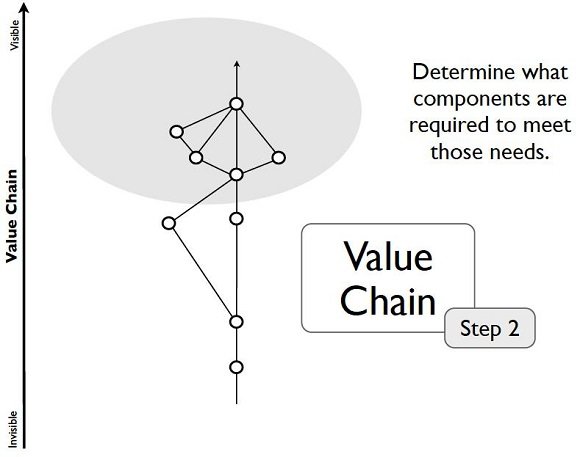

Step two: Value chain

We need to look at the capabilities needed to support these requirements:

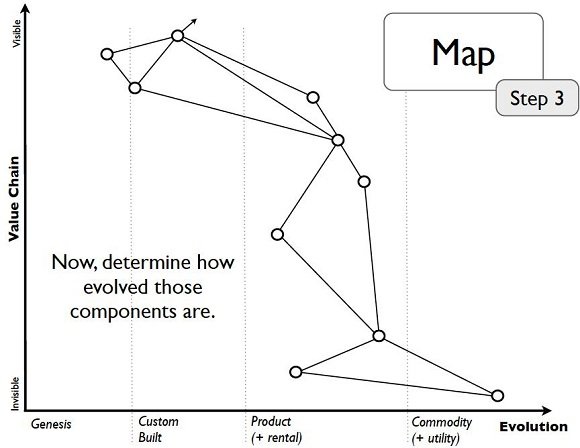

Step three: Map capabilities’ evolution and commonality in the value chain

We need to assess the relative evolution of each of these capabilities against what is available elsewhere in the market, and against similar capabilities that can be identified elsewhere within government:

Step four: Identify specific services or common capabilities for sharing across government

We then need to apply this consistent logic to identifying whether we should be developing specific services or common capabilities, as in this simplified example of technology developed by James Findlay, CIO for HS2:

Simon Wardley’s “capability mapping” reveals the hidden commonality of basic capabilities that underly many government services, towards the right of the map in step four above. Those capabilities towards the left of the map are candidates for MVP (bespoke services); those to the right of the map are candidates for MVC (shared capabilities) - or even consumption as utilities.

Clear methodology

Developing this definition of digital, organising principles and consistent approach into practice, we now require a clear operating model and enabling methodology to support what will be an ongoing, iterative activity, where, in each iteration, we:

- Identify & agree existing, vertically siloed business models for each public organisation

- Convert these into digital profiles, and;

- Add the segmented profiles into separately-run backlogs, as follows:

- Functions to be migrated to the growing set of shared capabilities (stewarded centrally in GDS): this will be a minimum viable capability (MVC) set for government

- Any additional MVCs to be built & added to the existing MVC set (above)

- Any minimum viable products (MVPs) to be built and maintained locally by the public organisation.

So how can government – central or local - get started and manage the ongoing digitisation process?

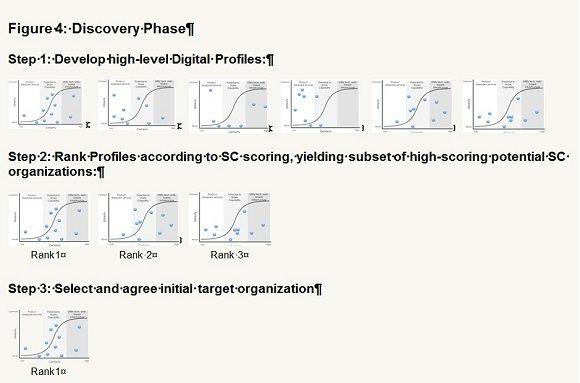

Getting started: Discovery phase

To get this ongoing Identify-Convert-Add “digitisation engine” up and running, government needs to first conduct a discovery phase, to prime the pump of the engine by identifying a subset of public organisations with the highest clusters of potential shared capabilities (SC). This initial exercise will yield a ranked subset of perhaps four or five organisations showing promising clusters.

For example, the digital profile on the left in Figure 3 will attract a higher SC ranking than the digital profile on the right:

| High-scoring profile |

Low-scoring profile |

| Figure 3a: High clustering of potentially shareable capabilities in middle column | Figure 3b: Less clustering of potentially shareable capabilities in middle column |

The output from this digital profiling and ranking exercise will be a set of ranked digital profiles from which a subset of candidate organisations can be selected that will feed the first three or four iterations of the digitisation process.

Next, an initial target organisation is chosen from this subset with which to create the foundational MVC set (including data), create an associated MVP set, and identify the required utility/infrastructure technology. This will prime the pump for the ongoing digitisation process as we move through further iterations.

The operating model for the discovery phase would look as follows:

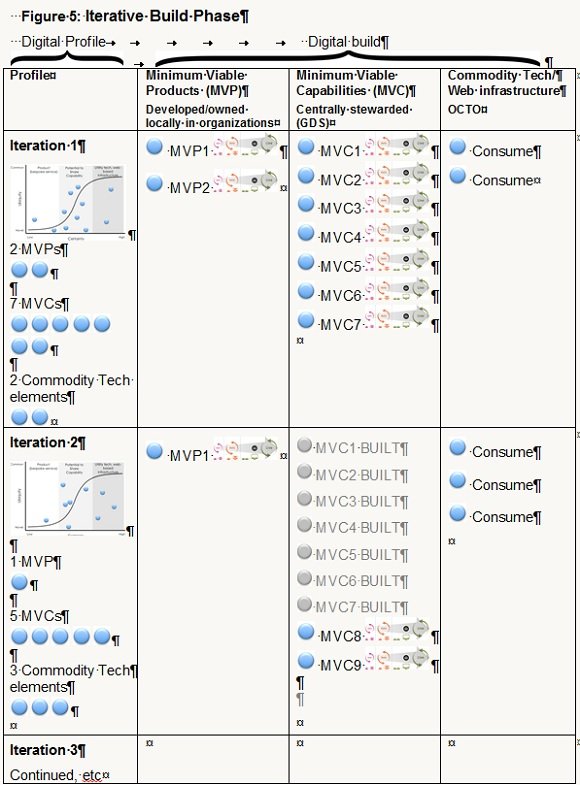

Ongoing, iterative “build” phase

On completion of the discovery phase, we will have both an initial target public organisation, as well as a digitally-related group of similarly-clustered organisations that score highly on potential SC. It is obviously important that the first organisation has a high SC score, to ensure that you prime the pump with a critical mass of capabilities in the MVC set.

We can then begin the first build iteration with the identified organisation, building the MVCs as identified in the digital profile, as well as the bare minimum of MVPs required for the digitised organisation to work, and lining up the utility technology/web-based infrastructure upon which it will sit.

This vertical and horizontal approach has the clear benefit of supporting a clear focus and priority on building a common capability set – while also rendering visible the other architectural components (MVPs, utility tech) needed to enable each digitised organisation to function against its remit. Everyone will be able to see where they are at all times.

In the operating model above, we can clearly see that the first iteration primes the pump by creating a minimum viable set of shared capabilities (MVCs). The digital profile also enables us to identify the MVPs that will be needed for a particular service to operate, as well as the underlying utility technology.

We can also see how subsequent iterations will migrate additional organisations to share or re-use existing shared capabilities – see the greyed-out ones in the MVC column - as well as identifying one or two additional MVCs - in this case, MVC8 and MVC9. In this way, we will gradually build up the MVC set common across government - and these shared MVCs will literally constitute the government as a platfom.

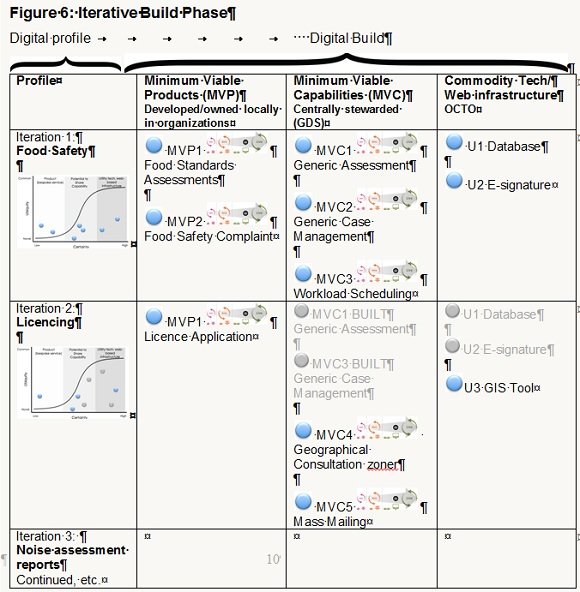

We can then migrate progressive public organisations onto the set – while ensuring architectural co-ordination with the minimum required MVPs and underlying technology for the newly-digitised organisations to operate and fulfill their remits. To make it a bit more real, here’s the same methodology applied to some of the great many case assessments undertaken across government:

Next steps

Achieving the sort of wholesale transition to digitally-enabled government envisaged in the above is likely to be a generational shift. Crucially, as well as the convenient, more navigable digital interfaces on offer, the public need to be made much more aware of the massive savings, and increases in face-to-face public services, that digital actually involves.

With the big numbers will come greater interest – and digital literacy -from our politicians. In turn, faced with a digital political mandate, HM Treasury will be forced to update its outdated approach to business cases, whose logic operates at departmental silo level, and is thus unfit for purpose for building cross-government commitment to the sort of undertaking outlined here.

Meanwhile, the “more taxes or fewer services” electioneering we hear every day sounds more and more old-fashioned - like politics from another era.

The author would like to acknowledge the input, support and encouragement of the many people who have helped evolve the thinking in this article – particularly the folks at Methods Digital (who are currently pioneering MVC in several places), as well as Rob Lawrence, Simon Wardley, Mark Foden, Jerry Fishenden, and Alan Brown.

Mark Thompson (pictured above) is a senior lecturer in information systems at Cambridge Judge Business School, a key architect of the government’s open IT strategy and strategy director at Methods Group. He is co-author of the book, Digitizing Government.