sdecoret - stock.adobe.com

The greatest contest ever – privacy versus security

Examining the technical, legal and ethical challenges around the privacy versus security debate

No organisation today can avoid the technical, legal and ethical challenges of the privacy versus security debate. In the blue corner, we have privacy – a true contender for the people’s champion. It has held the ring over the past 12 months, with the arrival of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) swiftly followed by privacy regulation across the globe.

Politicians and regulators alike have listened to the people demanding greater protection of their personal data when it is held by large corporations and government departments. They have responded with some of the biggest fines in the history of data protection, making privacy a board-level issue that has to be taken seriously.

As a result, organisations can no longer simply assume that any personal information given to them can be exploited in any way they see fit – a point illustrated very clearly by high-profile cases such as Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s grilling from the US Congress in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

And in the red corner, we have security, largely in the form of the new Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) in the UK – a “journeyman pro” that has had a fair share of defeats and setbacks in recent times. The IPA gives law enforcement greater and wide-reaching powers to capture personal information in the pursuit of criminals and terrorists who seek to do us harm.

This has been seen by some as the government becoming Big Brother through its monitoring of citizens. The initial version of this legislation was dubbed the “Snooper’s Charter”, but many failed to recognise that it was a response to bad actors getting away with crimes undetected, whether stealing money online or carrying out terrorist attacks.

It took time to realise that the previous legislation was only fit for purpose against fixed-line telecommunications, at a time when the bad actors were exploiting mobile phones, social media and even gaming platforms.

Ironically, organisations such as Facebook ended up being criticised for respecting privacy and not revealing information to law enforcement, but also being accused of harbouring illegal content and communications.

“Organisations can no longer assume that any personal information given to them can be exploited in any way they see fit”

Elliot Rose, PA Consulting

These developments underline that the contest between privacy and security has been long and difficult. Even three years after the IPA became law, it is still being challenged in the courts. In July 2019, a High Court challenge to the IPA by civil liberties charity Liberty was dismissed by Lord Justice Singh and Mr Justice Holgate, who concluded that the law was compatible with the Human Rights Act 1998.

The court also dismissed the argument that the law “does not contain sufficient safeguards against the risk of abuse of power”, but Liberty is continuing to challenge this latest ruling. Earlier in 2019, Privacy International won a case at the UK Supreme Court, which ruled that decisions made by the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) – the court that hears cases on surveillance and the actions of the intelligence agencies – are subject to judicial review in the High Court.

Privacy regulation has also been challenged, with some arguing that the new data protection laws promise to deliver more than is practical. By taking responsibility away from individuals and placing a legal responsibility on organisations, they may create unreasonable expectations for privacy and a false sense of security online.

This can be seen in the right to be forgotten. In many cases, this is difficult to implement in a digital world where information is cached, archived, reposted and replicated across global organisations. This is also creating a potential opportunity for bad actors to exploit.

Read more about privacy

- Cisco’s 2020 data privacy study shows organisations can generate substantial returns on their data privacy and protection spending.

- The Information Commissioner’s Office has published its Age Appropriate Design Code, a set of 15 standards that online platforms must meet to protect the privacy of younger users.

- IoT devices flood the market with promises to make daily life more convenient. Learn how to embrace user consent to benefit your organisation and enhance user data privacy.

For example, many financial institutions use risk-profiling from personal details to identify fraudsters who often repeatedly try to obtain money using false information. However, these fraudsters may use the right to be forgotten as a way to cover their tracks.

So, how should organisations respond? First and foremost, as technology advances and especially with increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI), much more attention needs to be paid to striking an ethical balance between the two sides.

Yes, organisations need to continue to ensure they meet all their obligations, be they statutory, legal or regulatory, but it is no longer as simple as that. They need to be aware that there will always be (arguably necessary) tensions and “grey areas” between privacy and security, where boards need to take an ethical view and have the evidence to back this up if they are challenged, recognising that, ultimately, they will be held to account.

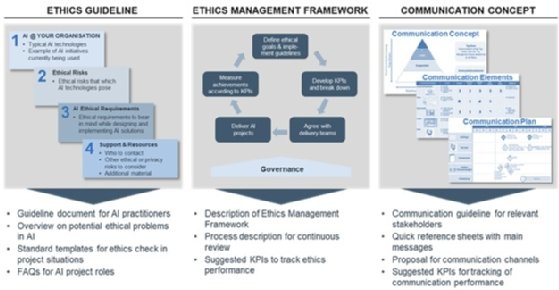

To make these ethical considerations business as usual for organisations, they should follow the three steps set out in the diagram below. The first is to draw up ethical guidelines for developing, procuring and applying technology, and these should be based on the organisation’s strategy, culture and values. Then they should create an ethics framework to apply the guidelines throughout the organisation and finally ensure that this is reinforced through communications and ongoing monitoring of compliance.

The fight between privacy and security may never be over and the ground on which it is fought will be ever-changing. So, organisations need to equip themselves to respond to the different needs, threats and evolving public opinion and make a virtue of how they approach this debate and the decisions they take.

Read more on Privacy and data protection

-

![]()

WhatsApp and Signal messages at risk of surveillance following EncroChat ruling, court hears

-

![]()

Counter-eavesdropping agency unlawfully used surveillance powers to identify journalist’s source

-

![]()

Government agrees law to protect confidential journalistic material from state hacking

-

![]()

Journalists’ confidential communications subject to unlawful spying, court hears