The Great Deverticalisation - part 3: New skills and structures in the public sector

Why do we persist in running vertically integrated organisations when standardising many of these processes would free us up to do things so much better, and more cheaply?

Why do we persist in running vertically integrated organisations when standardising many of these processes would free us up to do things so much better, and more cheaply? Mark Thompson with Jerry Fishenden, based on work being undertaken with Cambridge University’s Open Platforms and Innovation Group, continue to address this question in this third instalment of their series of articles for the private and public sectors alike. Read the first instalment here, and the second here.

Previously in The Great Deverticalisation…

The shopkeepers in the Street began to realise that maintaining their bespoke appliances had become so burdensome and expensive that they had no time left over to serve their customers. When they visited Market City, they discovered the world outside was doing things very differently – with a relentless focus on user needs. The Market City shopkeepers had created a common platform built on open standards that allowed them to have their cake and eat it – with cheap, locally-tailored appliances, each easy to assemble and run, and a crowd of suppliers vying with one another to think of ever cleverer, more innovative ideas to make them even better.

And so our story continues

The shopkeepers in the Street weren’t sure what to do next. Market City had shown them there was a much smarter way of doing things – one that would let them spend far more time meeting their customers’ needs, and spend far less time (and money) maintaining their expensive and somewhat cranky appliances. But they had so much time and expertise and money (especially money) tied up in their current way of doing things that the thought of changing everything made some of them feel very nervous.

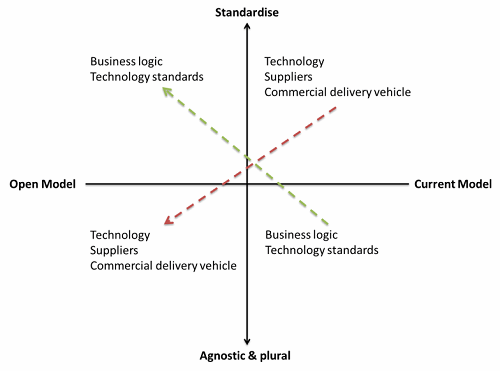

It was a complete reversal of everything they had known. In the past, they had specified suppliers, technologies and the way that things had to be bought. In future, they would not care about such things and would let the market compete to show it could meet their needs: but they would care about enforcing open standards and common business processes, something that in the past had never really happened.

Basically, they’d be moving from the right-hand side of the picture below to the left-hand side:

Some of the shopkeepers spoke to their traditional advisors, who were delighted to turn up in their colourful vans and soothe the shopkeepers’ worries with talk of their “special” and “unique” requirements that only they could provide. “We can build open things,” they said, coughing, while behind them their interns read quickly through Wikipedia to see what “open standards” meant.

The van-people nodded sagely: “Old black box proprietary silos bad, shiny new towers good”, they intoned. And when the shopkeepers scratched their heads and asked how a tower was actually any different to a silo, the van-people touched their noses wisely, winked and said “That’s for us to know, and you to pay for,” before they disappeared for lunch at the Siam Club.

Deverticalisation

Some of the other shopkeepers turned instead to ask for help from the Market City experts and some different (often smaller) suppliers they had not dealt with before, but who knew how to make such changes.

The shopkeepers started to design how the services could be run to meet the users’ needs – as simply and cheaply as possible, using open standards and re-using many commodity elements that already existed

The traditional van-people did not like this. They parked their vans in all sorts of awkward places to make life difficult and started to flap their fine vellum contracts about, which billowed and caught in the wind like huge kites since they were so big and long and riddled with endless clauses that only the van-people and their invoicing squads really understood.

The shopkeepers found the independent experts very refreshing. Instead of charging £1m an inch for bloated paperwork that proposed complex technical solutions for ill-specified problems, they instead started by asking who the users were and what it was they needed.

This was a revolution. In the past, the van-people had always started with a big technical solution and simply told users (if they spoke to them at all that is) to “get a life” when the final system didn’t work, and cost at least three times as much as they had originally estimated.

User needs

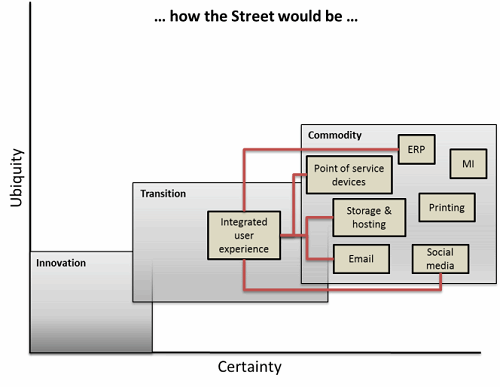

Once the experts had identified the users (shopkeepers, their staff and customers) and their needs, they then showed the Street’s shopkeepers that much of what they needed was not “special” or “unique” at all, and certainly not expensive. The shopkeepers started to design how the services could be run to meet the users’ needs – as simply and cheaply as possible, using open standards and re-using many commodity elements that already existed.

In the past, the van-people had bundled everything into big and expensive silos that the shopkeepers weren’t even sure the van-people understood themselves. But the shopkeepers acquired new skills from the Market City experts, learning how to deverticalise and disaggregate their requirements based on users’ needs.

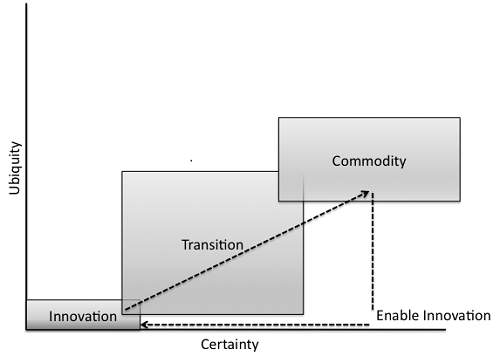

They did this by mapping user needs into one of several categories: “completely innovative and new” -where needs had never been met anywhere before; “in transition from being innovative” - with more commodity suppliers beginning to provide for them; or finally “complete commodities” - where a whole host of competing providers in the marketplace could meet their needs.

The shopkeepers started to break down their users’ needs and map them depending on whether they were at the Innovation, Transition or Commodity stages of maturity.

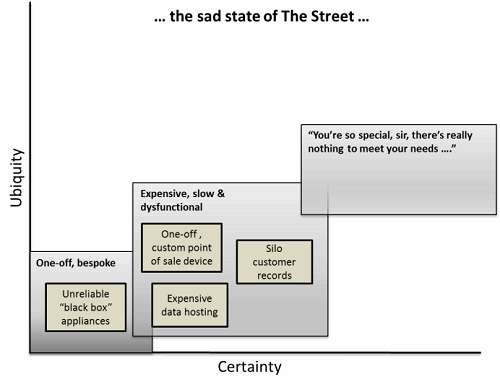

As they started to do this, they began to realise just why their current services were so poor and so expensive – the van-people had customised almost everything themselves. Even when they had used existing components and services, they had surrounded them with blobs of sticky and expensive code that only they understood.

Of course, the Street provided very different services to their users from Market City. Market City was about the cut and thrust of retail and consumer services, whereas the Street provided community services that improved the quality of life for its users.

But the more they worked at really understanding the user need and mapping it to their knowledge of what was actually available, the more they realised most of their users’ needs would be met by commodity services using open standards – the same basic stuff that Market City and everyone else used. For the first time, some of the shopkeepers began to see how the Street could be both much more effective at serving their users, as well as being much less expensive to run.

The shopkeepers decided to apply what they had learned to their most pressing services, which time after time had consumed vast amounts of money and yet delivered clunky old systems that never actually did what anyone wanted – to everyone’s Universal Discredit.

The Great Deverticalisation - read all the articles

Part 3: New skills and structures in the public sector

Worse, each time a supplier built something for one of them, they never re-used existing components, but built (and invoiced) for them all over again. This also meant that different users who needed to access important information failed to do so – because it was locked inside another tower (sorry, silo) that had been built for a different system.

But if all of this was going to work – not just technically, but to deliver major cultural and behavioural change too – and deliver better services for less, then it was not only the shopkeepers in the Street who needed to learn and change, but also their suppliers.

Next – part 4: the role of the private sector

Mark Thompson is a senior lecturer in information systems at Cambridge Judge Business School, a key architect of the government’s open ICT strategy and strategy director at consultancy Methods.

Jerry Fishenden is the former specialist adviser to Parliament for its inquiry into public sector IT and technology director at consultancy VoeTek.

Jerry Fishenden is the former specialist adviser to Parliament for its inquiry into public sector IT and technology director at consultancy VoeTek.