Minerva Studio - Fotolia

Should tech companies capitalise R&D spending?

Technology companies frequently ask whether they should capitalise their research and development costs. There are clear benefits, increasing reported profit and hence potential valuations, but what are the risks?

By far one of the most frequent questions we are asked by technology companies is: should we capitalise our research and development (R&D) costs? For many, it looks like a no-brainer – increasing reported profit, and hence potential valuations.

But is there really such a thing as a free lunch? Here we explore some of the pros and cons, look at which companies are choosing to take this route, and examine what it is giving them in return.

Most tech company valuations are based on revenues – including annual recurring or monthly recurring revenues, or profits, normally Ebitda (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) – which are regarded as a decent proxy for the profit the operating business generates before factors such as financing and tax, which could change when the company is acquired.

Capitalising R&D means moving some or all of the cost of your development team from above the Ebitda line to below the Ebitda line – effectively increasing the profit on which an acquirer might value the company – and taking costs that would normally be recognised on the profit and loss (P&L) statement and turning them into an asset on the balance sheet.

The logic for doing so is that the cost of that development does not match the revenues made in the current period but is being made to support future revenues – and so should be matched against those future revenues. In practice, this is done by amortising the capitalised balance over a period of time or, in other words, depreciating the expenditure on the balance sheet, rather than the P&L statement.

Conceptually, this is quite valid – provided the development cost genuinely relates to future revenues. And that’s where it becomes contentious.

Do the larger players do it?

They do, but much less than you think.

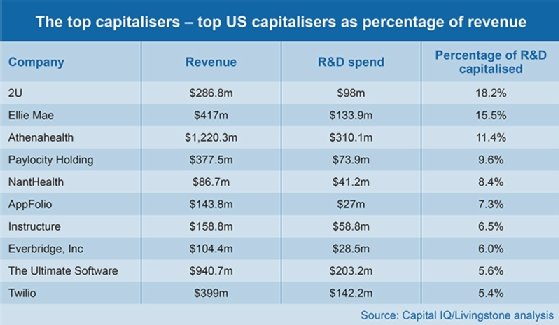

We looked at a sample of 74 US-listed software suppliers, spending over US$9bn a year on R&D between them, spanning enterprise resource planning (ERP) and supply chain, human capital management, communications, security, various specific verticals, and other software-as-a-service (SaaS) providers.

Of these 74 US-listed software suppliers, 44 (57%) capitalise some proportion of their R&D. The sample overall spends an average of 23% of revenue on R&D, and overall only 9% of the total R&D spend ($735m out of $8.3bn) is capitalised.

Of those that do capitalise, about one-sixth of their total R&D cost, or ~4% of revenue, is capitalised, with five-sixths (~19% revenue) expensed.

The decision to capitalise is not just based on scale – the largest in the sample, Salesforce.com (revenues $10.5bn) capitalises 0.8% of revenue; the smallest, Medical Transcription, capitalises 0.5% of its $32m revenue. Six of the top 10 by revenue capitalise, at an average of 4.2% of revenue; six of the smallest 10 by revenue do the same, at an average of 2.9% of revenue.

Nor is there any link to the absolute level of R&D spend, even at the smaller end – those that capitalise spend between $1m and $1.6bn on R&D – and again, both the smallest and the largest spender capitalise some proportion. Those that capitalise spend an average of $84m on R&D; those that expense it all spend an average of $83m on R&D. (For this stat, and this one only, we have excluded Salesforce.com (R&D spend $1.5bn, 0.8% of revenue capitalised) and Workday (R&D spend $900m, no capitalisation). The next-largest spender on R&D in the sample, Atlassian, spends less than half of this ($418m) on R&D, and doesn’t capitalise any of it.)

It does vary by subsector. More than 80% of vertically focused providers and communications software suppliers capitalise, whereas only one-third of other SaaS vendors do. About 40% of ERP/supply chain companies and security software businesses capitalise, as do more than two-thirds of human capital management suppliers capitalise. And in each of these subsectors, there are companies that do not capitalise.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the impact of capitalisation is to increase reported profit. The average Ebitda margin for the sample is -6%, and if all R&D were expensed rather than capitalised, it would fall to -8.5%.

Out of Facebook ($8bn R&D spend), Amazon ($23bn), Netflix ($1bn) and Google (Alphabet) ($17bn), only Amazon capitalises any R&D – $395m, which is 1.7% of its R&D spend, and 0.2% of its turnover. All the rest is expensed.

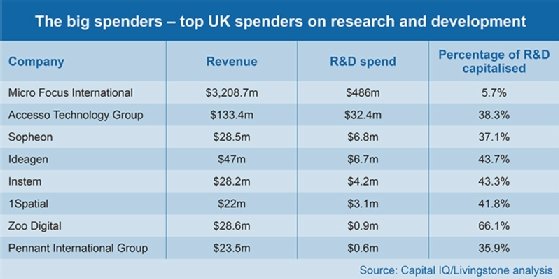

The picture is similar in the UK. While 57% of listed US companies capitalise some R&D, about 60% of UK software providers (11 of a sample of 18) capitalise some proportion of R&D, ranging from 1% of revenue to 9% of revenue. Again, there is no clear pattern based on subsector or scale – both the smallest (Osirium Technologies, £0.6m revenue) and the largest (MicroFocus, $3.2bn revenue) capitalise some R&D, and the same holds true for levels of R&D spend.

However, UK-listed companies are far more aggressive users of the practice. Those that use the policy capitalise about 40% of R&D spend, compared with 17% in the US sample, and an average of 21% of overall R&D spend.

The effect on reported profit is more dramatic, halving reported losses from an average of -28% if all R&D were expensed, to -14% after capitalising some of that expense.

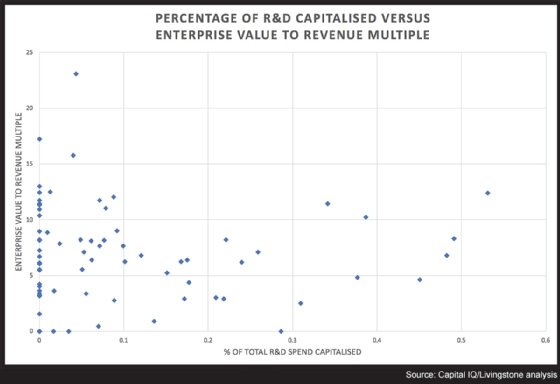

Does it support increased valuations?

No. A quick glance at the data (see chart) makes it clear that there is no close relationship. Regression analysis shows that increasing levels of R&D capitalisation (as a percentage of overall R&D spend) have very little impact on valuations overall. Across the whole US sample, for example, the r square is low at 0.008, and even looking only at those that do capitalise some proportion of R&D, it is only 0.002.

So you can do it – but should you?

For a start, if you are arguing that your business should be valued on a revenue multiple, then capitalising R&D cost to inflate Ebitda is a bit of a red herring. More seriously, it is clearly a well-established norm in the industry and a perfectly legitimate thing to do, permitted under US GAAP (Generally-Accepted Accounting Principles) and the IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards), which actually mandates it in many cases.

How much is too much?

In our experience, private and independent companies seek to capitalise significantly more than their listed peers – far more than the 17% of total R&D spend, or 3.7% of revenue, that our US sample capitalises. In the UK, this is in part because the norms set by listed peers are more aggressive, and because R&D tax credits provide an external – but very accommodating - standard, adjudicated by HM Revenue & Customs, of what counts as R&D investment rather than ongoing operating expenses.

But be warned: injudicious use will call into question the validity of your capitalisation policy, and the subjectivity of it will invite both scepticism and negotiation. Unless you have very clear, well-documented and demonstrably observed guidelines for working out what is capitalised and what is not, you risk looking like you are trying to inflate Ebitda, even if that isn’t the intention.

If you are considering a private equity transaction, you might also be storing up some structural problems. Even generalist (non-tech) private equity investors are increasingly accommodating of it, and in the current market will accept a level of capitalisation, but savvy debt providers are still focused on cash generation, and will look at your operational cashflow alongside your adjusted Ebitda.

If the incoming investor is valuing the business based on revenue multiples or Ebitda that reflects capitalisation, and your debt provider is lending on operating cashflow or Ebitda ignoring capitalisation, you are opening up a structural disconnect, and are likely to end up with an equity-heavy structure that might make it difficult for the investor to make the returns they need.

On balance, our advice would be to be cautious and judicious in your capitalisation. Make sure the arguments are rock-solid, the policy unambiguous, that the spend is demonstrably investment for the future and separate from any ongoing running costs. Be clear and transparent about it, early – don’t mislead and imply that the business is more profitable than it is.

And, particularly for tech-focused investors and strategic buyers, remember that their emphasis is likely to be on your revenue growth trajectory, or on the strategic gap you fill for them. Over-zealous capitalisation to flatter your accounting statements is likely to be a distraction at best, and at worst can undermine trust quite significantly.