Open standards are about the business model, not the technology

Software companies, abuzz with lobbyists and patent lawyers over government open standards, are similar to the record industry 10 years ago.

The activities of some of the large software companies, abuzz with lobbyists and patent lawyers over the ongoing UK government open standards consultation run by the Cabinet Office, are strikingly similar to the record industry 10 years ago as it thrashed about during the death throes of a similarly old-fashioned business model.

Desperate to turn the clock back, the record companies realised their intellectual property rights (IPR) were fused with an architecture - physical media - that no-one wanted anymore. Rather than separate the two and move on, they fought an ultimately unwinnable battle to persuade us that to access their IPR, we had to continue buying CDs. The very idea already now seems arcane.

And so it is with the current open standards consultation. Looking around some of the strands of this debate, you would really think that this was about this standard or that standard, this agreement or that law. But this is entirely to miss the bigger point. As with the record industry, development and consumption of software is undergoing a historically irreversible shift to a new business and commercial model that is enabled by technology – but where technology per se is increasingly unimportant.

The open model is starting to grow out of its traditional roots in hi-tech - think Amazon’s EC2, Google’s Android - and R&D innovation - think crowdsourced success stories from YouTube - and is now knocking at the door of almost everyone. As the open model grows it is beginning to challenge the commercial viability of traditionally organised corporate functions such as finance and HR, which, whether outsourced or insourced, will appear increasingly expensive if they ignore the emerging economics of doing things using common standards.

And this is why we’re having this discussion in the first place. Open standards increasingly allow a dis-integration of traditionally integrated business functions and technologies into discrete components - think automotive industry. In turn, this allows you to buy the more standard of these components more cheaply as commodities - high volume, low margin.

If government is able to move away from its traditional, department-based, siloed design and cluster similar components together, it will be able to take massive commercial advantage of its unique scale as a volume purchaser to create platforms around which suppliers of many different kinds will innovate, much more cheaply.

In an open marketplace, those who are prepared to componentise and standardise their businesses win in a number of ways over those who insist on maintaining an integrated, "bespoke" way of doing things.

First, they free themselves from long-term, monolithic outsourcing/licensing contracts involving entire functions such as finance or HR, in which innovative activity usually remains frozen within contractual service levels for the lifetime of the contract: in other words, they become more nimble and flexible.

Second, by separating out those components that are standard and low-risk, and which should thus be purchased as a utility or even consumed for free, there are major savings to be realised across the organisation. For example, although you might previously have thought of "finance" as a division to be outsourced, several components, such as "payments", "print services", and "accounts receivable" are increasingly available as utility commodities that can be consumed like water, or electricity, via the cloud. Others – such as the desktop - will surely follow.

Third, and perhaps best of all, an open, component-based view of government offers unprecedented opportunities to build and deliver new services to customers, by literally reassembling or swapping out components like interoperable cassettes. For example, I can set up a fully functional outlet for, say, delivery of social services in a morning – and run this out of a library building, or a school after hours, by assembling a combination of standard components that include case management, HR, and mobile IT. Such agility would have been unthinkable even five years ago.

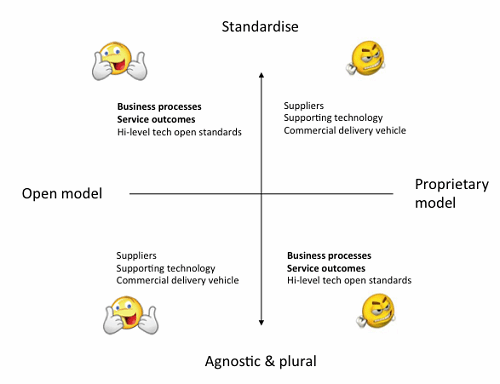

Look at this:

The left side of this picture shows that by standardising, or mandating, business logic and enabling technical standards, government can create a platform that enables it to be agnostic and plural in its approach to technology, suppliers, and commercial arrangements. This is like saying, “We want a service that achieves certain outputs, and complies with certain open standards so we can switch easily. Providing you achieve these, we don’t care how you do it, or what sort of supplier you are”. Such an approach places government in a position of commercial strength, exercising choice regarding technology, suppliers, and the most appropriate - preferably utility - commercial vehicle for services.

Compare this open architecture scenario with the right side of the quadrant – the "proprietary model" - which shows instead that government has for too long maintained exactly the opposite arrangement: it continues to standardise on technology, suppliers, and commercial vehicles – for example, restrictive frameworks, constrained outsourcing contracts. This is like saying, “We have standardised on company X’s products and standards; we therefore purchase from company X; and we have a long term licensing agreement with company X – and will adapt our own business logic and standards to fit their application”.

Within such arrangements, government is purchasing (technology) inputs rather than (service) outputs, and it becomes locked in to proprietary standards and processes controlled by the supplier, with whom it occupies a correspondingly weak commercial position.

It is for this reason that the government’s open standards policy is about much more than technology arguments, or the rights, legal or otherwise, of technology suppliers with outdated business models to "sweat their assets" on the government for as long as they legally can.

What is at stake is nothing less than the continuing viability of public services in a future era of unprecedented financial constraints; of digital-era, rather than physical-era, models of public service delivery. The Cabinet Office has embarked on an attempt to prepare this country for such a future – a fundamental transition in business model against which the current debate will one day be seen as a bad-tempered skirmish in the foothills.

It is very clear indeed that the current open standards consultation is an attempt, driven by nakedly commercial interests, to force government back into the right-hand side of the quadrant, where it can be locked down again into arcane debates about standards, version upgrades, compatibility, and so on – in other words, a focus on technology, rather than outcomes.

We are being told that we should continue to care about – obsess about – and, importantly, pay for this stuff. As the free, always-latest-version software on my MP3 player indicates (I’ve no idea who made it, and don’t care), history is likely to prove otherwise.

Dr Mark Thompson (Cambridge University, Methods Innovation and Delivery) authored an initial paper for chancellor of the exchequer George Osborne in 2008 setting out the case for the creation of a level playing field for technology founded on progressive adoption of open standards. His ideas have subsequently appeared in several white papers and Cabinet Office policy documents exploring the radical implications of open standards for public service delivery in the UK. Mark (pictured above) has authored, with Jerry Fishenden, the only top-tier peer-reviewed journal article on open standards and public services: "Digital government, open architecture, and innovation: Why public sector IT will never be the same again", forthcoming in the Journal of Public Administration, Research, and Theory.