Jerry Fishenden

Implementing a 21st century approach to digital identity

The government’s attempts at digital identity have failed – it is time for a new, modern approach

The UK is fortunate. Unlike many other countries, we don’t have the baggage of state-issued ID cards rooted in the intrusive mindset of “papers please” officials and central surveillance registers. This leaves the UK well-placed to take the lead on implementing a 21st century approach to identity. One that places the individual at the centre, meeting citizens’ needs in an increasingly digital, internet of things (IoT) world. An approach that sends a confident message about an outward-looking, innovative, post-Brexit modern democracy that embraces identity as a means of personal empowerment rather than state or corporate control.

Proof of identity

Let’s face it. For all the endless debates, articles and international events about identity, we don’t need to prove our identity very often. On the rare occasions when we do – to open a bank account or apply for a job, for example – we rely on trusted documents such as passports and driving licences issued by the government.

It’s this government-assured information about us – such as our name, date of birth and photo – that underpins most proof of identity, from the finance sector’s Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations to employers’ checks when offering a job.

These paper-based approaches don’t work so well when we want to prove who we are online. It would be more convenient if we had a secure digital way to prove something about ourselves, mirroring what we achieve face-to-face with bits of paper. A digital way of providing appropriate proof – such as our age, name, address, right to reside, work or study in the UK – without having to scan and upload our documents.

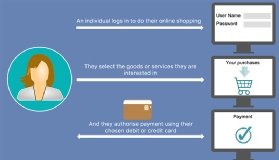

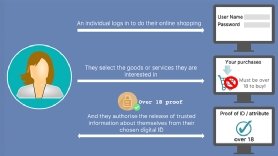

We need a better, more convenient and effective solution to identity. One that lets us manage our own identity-related data and choose where, when and with whom we share it. Think of the way, for example, that we’re all familiar with using credit and debit cards to authorise payment both online and offline.

A well-designed secure ID could work much like this familiar payment authorisation process, providing an easier-to-use and more secure way of proving something about ourselves.

We keep our credit and debit cards secure and only use them when we need to authorise payment. In the same way, we would only use our secure ID on the rare occasions when we need to prove something about ourselves – such as being over 18 when buying alcohol or knives from an online retailer.

Characteristics of good identity

If we are going to trust digital identity, it should work in much the same way as a passport. When we use a passport to prove our identity (rather than to travel across a national border), no one other than the passport holder and the organisation or person we share it with knows we have used it for this purpose. The Passport Office does not require us to notify where, when and with whom we have used it.

Good digital ID should work in the same way, letting us decide when, whether and with whom we share information about ourselves. The characteristics of a good approach to identity include:

- We can choose whether to use it or not – we should not be forced to use it.

- It must provide support for those who do not currently have “standard” identity documentation, such as passports or driving licences.

- There must be no monitoring by government or other organisations of where, when and with whom it is used. Identity should be about precisely that – proof of identity or something about ourselves – not surveillance by companies or governments.

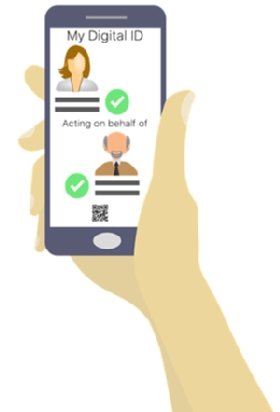

- Individuals should have control of their data and be assured of strong security and privacy. This should include the ability for us to delegate authority to others to act on our behalf (such as a relative with Power of Attorney).

- It should not share information with another person or organisation unless they can also prove they are who they claim to be – proof of identity should be reciprocal. This will help reduce scams where we get fooled by fraudsters impersonating somebody else, such as our bank.

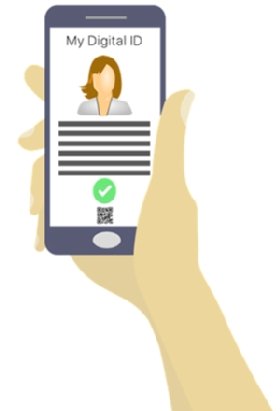

- It will provide the ability to work both online and offline. A smartphone digital ID app is one obvious way of doing this, although non-digital alternatives should also be available for those who want them.

- Only the minimum amount of information will be released. Rather than revealing our full name, date of birth, place of birth and so on, if we only need to prove we are over 18 to buy a knife from a kitchen shop or order a pint in the pub, it should simply show “Over 18” alongside our photo. This will help reduce the amount of personal data taken and potentially lost or misused by organisations when we interact with them. Dave Birch’s 2009 paper Psychic ID: A blueprint for a modern national identity scheme remains an entertaining introduction to the way well-designed ID minimises the amount of personal information we disclose.

Not only would a good digital ID therefore let us do everything we can currently do with a passport, but it would be an improvement, better protecting our privacy and personal data. It would also be more convenient. If, for example, we can store our identity-related information on a smartphone, we could use it both online and offline when we need to prove something about ourselves.

Learning and moving on

Before we can start implementing a more secure and better way of managing identity, we need to reflect honestly on the failed attempts to crack the problem over several decades of hype and disappointment.

Back in the last century, the UK government hoped that trusted third parties would provide a “marketplace” able to provide citizens with their digital identities. Since banks were responsible for Know Your Customer and anti-money-laundering checks, the theory was that they would be natural outsourced providers of digital ID. After some promising early work in the 1990s, including with Barclays, NatWest, the Post Office and the British Chambers of Commerce, the outsourcing of identity to trusted third parties failed in the early 2000s.

The next notable attempt to tackle identity was the brief flirtation with national identity cards and the national identity register from around 2004 to 2010. When these were scrapped by the coalition government in 2010, the Identity Assurance Programme revived the idea of outsourcing identity to a marketplace of trusted third parties. It later became Gov.uk Verify. The Verify service has a well-documented troubled history and government spending on it is scheduled to end this March. There is no real evidence of any marketplace – if there were, we would expect the market to have provided solutions and services long ago.

The Verify programme’s efforts to glue together two separate services – trusted digital identity and how we authenticate to online services – created several undesirable and unintended outcomes. Citizens who were unable to successfully sign up for a Gov.uk Verify digital ID with one of the programme’s contracted businesses found themselves denied access to government digital services. Since less than 50% of citizens were successful in obtaining a digital ID from a Verify identity provider, this approach left the majority of citizens unable to use a Verify ID to access online public services. The commercial identity providers effectively became exclusive gatekeepers determining who could access online public services and who could not.

Even those citizens who were successful in creating a commercial Verify account could later lose access to their public services if an identity provider withdrew from the Verify scheme. This is a significant issue given that most of the Gov.uk Verify providers have now withdrawn. Many individuals will lose access to their digital public services as well as their Verify digital ID over the next year.

The Verify model was based on a doubtful assumption: that a commercial company needed to be inserted between citizens and their public services. However, citizens generally don’t expect or want commercial parties sitting between themselves and their public services, including their online tax or medical records. This was been repeatedly confirmed by user research, from the early days of the Gov.uk Verify programme to more recently by the Scottish Government and the NHS.

The user research and various difficulties encountered by the Verify programme illustrate the need to tease apart the way we prove something about ourselves from the way we authenticate to online public services. The government needs to ensure that citizens are able to access digital public services in the same way that we’re all able to access face-to-face services. And we should be able to do so without being forced to sign up with a commercial intermediary which has no justifiable place in that relationship.

Public sector organisations should be free to manage their own solutions for authenticated access to their online services. Government is well-placed to identify the users of digital public services using information it already holds – and was already successfully doing so across government before the Verify programme came along and revived the 1990s model. At its peak, for example, HM Revenue & Customs’ (HMRC) service for authenticating to digital services across the public sector was reported to be supporting over 120 live digital services, more than 400 million identity authentications a year, and over 50 million active accounts.

The good news is that the UK government still has its own authentication services for citizens and businesses to access online public services, as the NHS, HMRC, and Scottish Government’s myaccount, among others, demonstrate. With the imminent demise of Verify, the public sector can continue providing and improving its trusted ways for us to directly access our digital public services.

The government’s focus can now turn instead to the original issue: how do we cultivate a secure, trusted approach to identity that works online and meets our needs in an increasingly digital economy?

Provide digitally what we currently get on paper

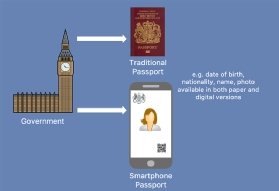

There is a relatively small set of our personal data involved in establishing basic proof of identity – essentially the government-assured information contained in our passports, such as our name, date of birth, nationality, place of birth and photo. To move us into the digital era, the government could provide us with smartphone versions of our passports and driving licences.

This is not a new idea. Three years ago, DVLA announced it was working on a smartphone version of the UK driving licence.

Smartphone versions of passports and driving licences could include privacy-enhancing security features such as minimal disclosure. For example, a smartphone passport would be able to confirm the status of the holder (British national, over 21, or whatever, together with a facial image to confirm the data relates to the person presenting it) but without releasing the entire set of personal data. The Scottish and Canadian governments, among others, are already exploring such attribute-based approaches.

Identity apps need to be designed and engineered in a secure and privacy-friendly way to build trust. They should avoid the downsides of identity cards, which often snoop on where, when and with whom a card is used. 21st century digital identity needs to be about precisely that – identity – and not polluted by state or private sector tracking, surveillance and control. The Apple Card illustrates some of what’s already possible with secure, privacy-aware technology – ensuring that even Apple doesn’t know what someone bought, or where, or how much they paid.

Digital versions of our passports and driving licences would meet the needs of many people and organisations and be a useful and practical first step. Alongside this, it would also be useful for government to release the same assured data in a format we could take and use in our own choice of digital apps or services.

There are a variety of options for where we might choose to store and manage our government-assured data – from mobile apps, to online service providers, to letting us store and manage it ourselves on a server running at home if we are so inclined.

Innovative UK companies such as Yoti are already providing user-controlled apps that let people build up and manage their own digital identity profile.

We need agreement on the technical standards and processes required to start issuing our trusted data to us in a secure format for use in our choice of digital identity products and services. In the meantime, the chips embedded in most UK passports contain the same data that’s printed inside (such as our name, date of birth, place of birth, and photo). This data can be accessed, retrieved and used in smartphone digital ID apps, as the Yoti app and the Home Office EU Exit: ID Document Check app demonstrate.

Used alongside assurance processes to check the individual is the live and legitimate owner of the passport and its related data, ePassport chip access provides a relatively quick way of getting digital ID started. As an important additional security check, the pilot to open up the government’s document checking service will enable trusted identity app and service providers to validate that a passport has not been reported lost or stolen.

It’s also important for us to know which digital identity apps and services can be trusted and which cannot. Some form of listing or accreditation of trusted digital ID app and service providers will be required, similar to the way that Open Banking service providers are regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Start making other data available

Our identity is, of course, about more than government-held data such as legal confirmation of our name and date of birth. Our identity is a unique biological and biographical blend of a wide-ranging mix of attributes, including those drawn from many different relationships and pieces of personal information held by many different organisations and people.

Once a baseline of identity-related data is available in a secure digital format, other government-held data could start to be made available in a digital format if citizens and organisations find it useful.

Alongside this trusted, government-assured data, we could also start to add data from other sources if we find it useful and choose to do so. For example, we might want to obtain proof of exam results, or professional accreditation, to store and use in our digital identity apps.

One potential option is to use our existing online accounts with banks, HMRC, the NHS and others to authorise the release of data to our chosen apps and services. Open banking already shows how this can be done. It lets us use our bank credentials to authorise the release of our financial data to an accredited app or service provider, while remaining in control of our data at all times. This opt-in, secure approach could be extended to other trusted services outside of banking, enabling us to authorise the release of data into our chosen identity application or service.

The benefits of secure 21st century identity

An ecosystem of trusted apps, services and data, all under direct citizen control, would let the UK implement an improved approach to identity and related data management fit for the 21st century. It would help individuals prove something about themselves when they need to, such as when opening a bank account, applying for a job or buying restricted goods online.

The government would know nothing about these interactions, in the same way it doesn’t know when someone uses their passport to open a bank account or provide proof of age in a shop. Digital ID would be as private as our use of current paper passports but have the added advantage of working securely online, disclosing and sharing less of our personal data. It would let us keep a secure audit record of where, when and with whom we have disclosed our data or attributes – a record that is ours, that we control and manage. It would help improve our security, and help reduce fraud, forgery and misuse.

For a system of citizen-controlled digital ID to be widely accepted and relied upon, it needs to be:

- Trustworthy – it must come from an authoritative source and be clearly associated with the individual presenting the digital ID. The use of a strong authentication credential and a facial photo, to bind the individual back to their data as with passports, remains the obvious way to do this.

- Secure – it’s essential we can demonstrate that trusted personal data have not been tampered with or altered in any way since being issued.

- Private – the individual must be in control of the management and use of their own data. When they prove something about themselves, there must be no tracking of the interaction by anyone other than the user and the person or organisation they interact with.

- Attribute-based – digital identity apps should only release relevant attributes (over 18, has the right to work, and so on) rather than raw data, such as date of birth, wherever possible.

- Verifiable – for some purposes, it will be important to ensure that relevant data is still current. This must be achieved without revealing where, when or with whom an individual is using their digital ID. An individual should be able to update the information in their app or service directly with the authoritative original source before they share it with a third party, preventing the original source from knowing where an individual is using their ID.

Making it happen

We need a standard way of acquiring, securing and sharing our personal identity-related data and of being able to prove it came from a trusted source. We also need a standard and consistent way of using our digital ID when we need to – as we already have standard ways to make credit or debit card payments both online and in person.

We already have a very well-proven basis of trust around identity rooted in government-assured processes and the UK passport and driving licence that we can mirror in the digital world. We also have the interoperable trust frameworks, such as the European Union’s Electronic Identification, Authentication and Trust Services (eIDAS), and technical standards, such as W3C Verified Credentials and Decentralized Identifiers, required to deliver trusted digital identity. By re-using existing frameworks and standards, the UK’s digital ID could work well beyond the UK’s borders too (as our paper passports already do), which would be useful for businesses and citizens alike.

Legislation and regulation will doubtless need updating to recognise the legal equivalence of digital ID to paper proof such as passports or driving licences – for example, as part of the KYC checks in banking.

It’s also important that we avoid the undesirable growth of a “papers please” culture. As it becomes easier for us to prove something about ourselves, we should not let organisations arbitrarily begin asking us to prove our ID just because they can.

For those who cannot or will not use technology, we also need a complementary approach, something like the CitizenCard perhaps, to be made more widely available. This would provide citizens with a choice of how and where to obtain a non-digital equivalent, particularly those who struggle to prove something about themselves because they don’t have either a passport or driving licence.

Next steps

None of what’s set out here is technically complex, politically radical or challenging. It follows the KISS principle: keep it simple, stupid. It proposes extending the same trusted and familiar approach to identity that has worked well in the paper world into the digital one, while adding improvements in terms of usability, security and privacy. It can be delivered in practical, incremental steps for those who would find it useful.

There is a great prize to be seized in the post-Gov.uk Verify, post-Brexit world. The biggest mistake the UK could make is to remain hostage to the sunk costs and failed approaches of the last century.

The details outlined here complement and support work already happening, including that of government departments, the Scottish government and the private sector. The UK government has the opportunity to be the catalyst for a viable, practical, accessible and inclusive approach to identity.

The UK has a wealth of talent, across government, academia, civil society and industry, that can position us as a world leader in secure, privacy-enhancing and trusted technology. Imagine a system that not only provides trusted digital identity and related data management for UK citizens and businesses, but which also enables the UK to champion and export a secure, trusted, privacy-enhancing approach. An approach that helps displace the outdated, invasive and often dehumanising mindset around identity still prevalent in much of the world. An approach that’s fit for the digital age and the increasing prevalence of the internet of things.

At a time when democracy and freedom face increasing threats, the UK can play a leading role in their renewal and protection. We can seize the opportunity to send an inspirational message to the world – that technology can be designed and used for good, to enhance and promote the values of democracy, freedom, and privacy rather than to undermine them.

It’s time to drop the worthy but discredited conference-slide theories of the last century and instead adopt a practical, secure and trustworthy approach to identity. Whether the government seizes the opportunity to do so during 2020 will be an important early test of the political appetite to create a confident, innovative and digitally savvy post-Brexit UK.

Read more about digital identity

- Identity custodians needed in digital era.

- Government launches digital identity consultation and new pilot scheme.

- What the UK can learn from the Nordics when it comes to digital ID.