NicoElNino - stock.adobe.com

Harnessing the promise of data from space services for a better Earth

Mark Chang, an aerospace, defence and security expert at PA Consulting, looks at the actions that organisations need to take to harness the potential of space services data

Space – the final frontier. Today, it is the frontier of economic activity driving all types of daily activity. The user base is growing, stumbling into a future where space data moves at higher velocity, with bigger volumes, more volatility and is increasingly necessary to everyone’s lives.

Raw space data is estimated to have a direct impact on 120 million users. By comparison, social media giant Facebook has about 183 million users. Projections suggest space data volumes will increase by two orders of magnitude by 2030, making it critical to think about a data management strategy. Without that mature strategy to harness these changes, we will miss opportunities to exploit data-fuelled insights to benefit our economy and environment.

Space services for Earth applications provide data from three broad categories: communications, position, navigation and timing (PNT), and Earth observation and Earth science.

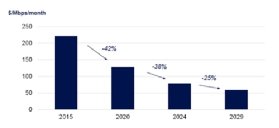

We expect data volume and quality in these areas to be a mix of big step-changes and organic growth. Driven by falling costs of both technology and access to space, satellites are already delivering data to improve life on Earth, helping to predict natural disasters or enabling us to use resources more wisely.

If the world’s population reaches 9.8 billion by 2050, as forecast, more sustainable ways to manage both food and water will be needed. Global insights must underpin decisions in these areas. One way to secure the global near-real-time resource distribution data required to support these insights is to use the new industries (terrestrial and cis-lunar natural resource mapping from space, consumer tourism in space), new infrastructures as well as the commercial activities in space that were once the focus of governments.

The cost to build and launch a small satellite has become comparable to the cost of developing a software app, so even university student groups can do it. About 40% of the satellites in orbit are there for commercial purposes, many funded by venture capital.

A lot of startups are providing low-Earth-orbit satellites for a range of different, innovative uses. Take transport infrastructure – satellite imaging technology can provide vehicle traffic monitoring with improved reliability and context compared to GNSS and opens up opportunities for innovation. When both infrastructure and vehicles exchange telemetries to respond to real-time environmental conditions, as smart cities aim to do, space data will be part of smart logistics decision-making.

Without a coherent approach to data exploitation, and few market regulations, the conditions for harnessing these developments to create sustainable and fair big-data marketplaces will not be right. This will make it harder to access useful data and reduce the opportunities to obtain insights through digital business functions. What we are currently seeing is that corporations have stepped in and tried to control access, with little oversight of their activity, and we risk the emergence of unconstrained data monopolies that disadvantage everyone else.

As new user groups are established, the different types of data combinations will require different handling to meet business needs. Data use must be regulated, but not constricted, to allow for ingenious new uses while preventing harm and permitting shared benefits. This could be an international regime, enacted by treaty or soft-law mechanisms, ensuring compliance with international legal principles.

As architect and orchestrator, government should take an adaptive governance approach, involving all actors, to be most effective. What does that imply? At its core, adaptive governance is collaborative “learning by doing”, where the process of resolving uncertainty in governance is active management through monitoring, to enable better implementation or operational decisions.

One of the particular challenges to manage is that data has a lifecycle and big space data has a very complex one. Efforts to extract insights from unmanaged data is, at best, inaccurate or pointless, and at worst, misleading. Should Earth observation image data, say, be offered at the right resolution and quality with reasonable prices, interests ranging from agriculture to construction would drive the demand. Without curated datasets, these audiences will end up with a fractured data landscape and opaque insights.

All this means we must understand the state and the health of data available, now and into the future, to provide the right oversight of how it is provided. The state (at rest, in transit, in use) can be obtained from technological systems or analysis. The health must be determined from a combination of analysis, calibration and testing.

Only then will we be able to design a coherent space domain industrial-economic strategy, where the data is allowed to “flow” to businesses through equitable marketplaces.

To meet these challenges, all stakeholders with interests in space data need to:

- Visualise and know their data supply chain and what it means for them.

- Be clear about what services they want to develop and know the strengths and weaknesses of new space services.

- Understand how the value of the big data will change over time and have a strategy to respond.

- Actively manage data security at the most vulnerable points in the global infrastructure.

As space data grows, those enterprises with a mature, relevant strategy that tackles these questions will be able to harness the changes and benefits, leaving those without far behind.

Mark Chang is an aerospace, defence and security expert at PA Consulting

Read more about space data

Space junk revealed by University of Texas graph database.

Amazon sets about speeding up space data processing in the cloud with AWS Ground Station.

UK satellite data to spearhead fight against climate change.