Inside Israel’s cyber security operations

An emergency phone line allows cyber security analysts at the Israel Computer Emergency Response Team to map threats against national infrastructure

Israel’s cyber security operations are being conducted in Be’er Sheva, the country’s largest city in southern Israel’s Negev desert.

Israel’s Cyber Emergency Response Team (Il-CERT) provides a first-line response to companies and citizens affected by cyber attacks.

The CERT is part of a cyber security hub of startup companies, supported by the Ben Gurion University of the Negev, high-tech innovation labs and the Israel Defence Forces’ cyber and technology campus.

Some seven Security Operation Centres (SOCs) operate alongside the CERT, monitoring, detecting and analysing cyber threats across different sectors of the economy, including water and energy, public services, and police and emergency services. Work is underway on another six SOCs.

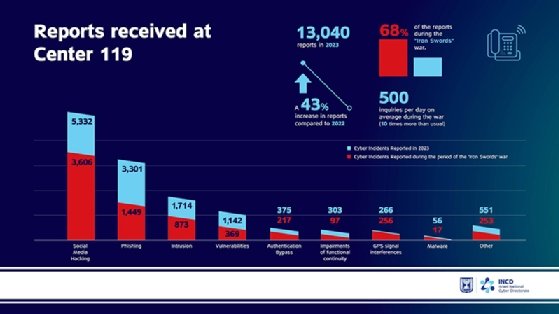

At the heart of the operation is an emergency 119 telephone hotline available for anyone to phone in reports of anything that could be linked to a cyber attack. That could be a suspicious email, a suspicious URL or malware.

The hotline is widely used by everyone from young people who have been sent a suspicious link on social media to company executives who believe they have been hacked.

By mapping the incidents, the CERT’s cyber security experts are able to see national trends and identify the most critical hacking attempts for the CERT’s response teams.

Executive director

Dana Toren is the executive director of the CERT. A former intelligence analyst and data analyst at the Prime Minister’s office, she is responsible for overseeing the CERT’s operations.

“We need to understand whether incidents are of national importance,” she told Computer Weekly.

An attack against a small company, for example, could impact many other companies that rely on its services.

Last year, the CERT received 13,000 incident reports, an increase of 43% over the previous year.

In the 270 days since Israel declared war on Gaza, the CERT has identified 1,900 significant cyber attacks against Israeli companies, and the nature of the attacks has changed.

Now they are designed to cause damage to Israeli infrastructure, and the number of ransomware attacks has increased. Iranian-backed groups seek to publish hacked data on the dark web or leak it to the media.

Biggest threats

Gaby Portnoy, director general of the Israel National Cyber Directorate (INCD), identifies Iran, Hezbollah and Iranian-linked hacking groups as the biggest cyber threat against Israel, and their attacks have become more severe since the war. “Until 7 October, they didn’t attack hospitals,” he said. “From 7 October, all the Israeli hospitals were attacked by Iran.”

Toren said that although Iran plays a big role in attacks against Israel, the emergency response team is more concerned with reacting to cyber incursions than identifying who was behind them. “It is difficult to attribute attacks to specific players,” she said. “Everyone uses the same tools. [We are] a defensive organisation. We do not deal with attackers. We only protect industries.”

The CERT’s control room contains work stations for a dozen people and 10 large wall-mounted displays. One display is a map showing real-time cyber attacks collated using intelligence supplied by US-Israeli cyber security company Check Point.

Another screen displays the websites of companies defaced by hackers. Analysts check them twice a day and alert the organisations impacted.

Since the war started, Toren has increased the number of people working full time at the CERT from 90 to 120 employees.

Organisations that make up Israel’s critical national infrastructure, such as water, electricity and hospitals, are legally required to report cyber breaches. But for the others, the 119 phone line is voluntary.

In return for phoning in reports, companies and individuals receive a confidential advice service. For example, the CERT will not report cyber attacks to regulators, or publicly identify which organisations have been hacked.

The CERT provides advice and recommendations to people who call the helpline with cyber security issues.

Its resources are limited, however. It has four teams of incident response investigators making up a response team of only 16 people.

“We need to think carefully before we provide this service,” said Toren, given the CERT’s limited resources.

Teams are only deployed in cases of national importance and where an attack on one company could pose a threat to a wider industry.

Hack affected 80 companies

In one such case, CERT investigators discovered that an Iranian-linked hacking group had infiltrated a small supply chain company, and had used that company as a stepping stone to infect a further 80 organisations.

The attack, which took place in 2020, had the potential to disrupt oil imports and exports to Israel, Toren told Computer Weekly.

“We had three or four calls on 119 who reported they had been attacked,” she said. “At first, we could not find a connection.”

Then a private cyber security response company called to report that an inventory system company had been hacked.

“We immediately contacted them and told them we believe there is a hack in your network,” said Toren. “It was a Friday and we sent an incident response team.”

The investigators were able to identify the signature – or indicators of compromise – of the hacking operation in time to alert the 80 organisations at risk.

The malware was identified as Pay2Key ransomware software associated with the Iranian-linked Fox Kitten hacking group.

Vulnerability scanning

Another role of the CERT is to warn organisations about security weaknesses in their computer systems. The INCD stepped up its vulnerability scanning programme following 7 October, said Portnoy.

Hospitals and other critical services have received at least six “attack surface” checks of their networks to identify weaknesses that could be exploited by hackers.

INCD also scans the dark web to identify passwords or other critical information that could expose company networks.

The operation covers 5,000 organisations and some 33,000 IP addresses. “They deep scan the infrastructure to find systems open to vulnerabilities, and we contact them to provide guidance on how to fix them,” said Toren.

Other alerts come from End Point Detection and Response probes placed on organisations’ networks to provide an internal view of their cyber security.

Once the CERT has identified the signature of an attack, known as “indicators of compromise”, they are shared with other organisations on an application programming interface, which can automatically update cyber defences.

But there is a recognition that more needs to be done. Israel began a project to improve its cyber defences in 2021.

Known as Cyber Dome, alluding to Israel’s anti-missile Cyber Dome system, it aims to use AI and big data to detect and mitigate attacks as they happen.

At the same time, Israel is stepping up co-operation with other countries on developing cyber defences.

Lessons from the Stuxnet attack against Iran’s nuclear facilities

The cyber operations centre for Israel’s energy industry is a short walk down the corridor from Israel’s main Cyber Emergency Response Team.

This unit is part of the Ministry of Energy rather than the National Cyber Security Directorate, but it shares expertise with tech companies, the university and government organisations around Be’er Sheva.

A bank of screens on the wall show cyber security events in energy companies, and also monitors factors such as temperature, voltages and turbine speed.

“Cyber security is a learning experience,” said Assaf Turner, head of the Sectoral Cybersecurity Unit for Energy. The unit, he said, is collaborating with the US and Europe to share information on security vulnerabilities in control equipment used to control power plants.

One lesson Israel learned 15 years ago is that cyber attacks on critical infrastructure are not always visible from a power plant control room.

In 2010, an attack using the Stuxnet worm disabled 1,000 centrifuges that the Iranians were using to enrich uranium. The worm, which has been attributed to Israel and the US, later escaped to infect other computer systems around the world.

Iran’s control rooms showed that enrichment plants were behaving normally when the centrifuges were spinning out of control.

Israel’s Ministry of Energy is working with universities in Israel and Germany on a project to detect similar attacks in future by monitoring vibrations, temperatures and other variables.

“We are trying to see what happens so that if a device starts spinning, we will know before a cyber event is detected,” he said.