Romolo Tavani - Fotolia

Met Office bids to make climate data more accessible with Esri

The Met Office is offering a new data portal, built on Esri’s geographic information systems technology, to enable users to understand local and national impacts of climate change

The Met Office has made available a climate data portal aimed at helping organisations better understand and respond to climate change.

It is part of a long-standing partnership between the Met Office and Esri UK, whose geospatial technology stands behind the portal. The organisations say it will make it easier for businesses and government agencies to combine open climate data with their own data.

Jason Lowe, head of climate services at the Met Office, said in a joint statement with Esri UK: “Historically, climate science has defined the problem, now it’s moving to help with the solution, providing information at a local level which is highly relevant to UK organisations.

“By combining the Met Office’s latest projections with Esri’s geospatial tools, the reach and value of this data is greatly extended. UK stakeholders can investigate their physical climate risks over the next 50 to 100 years.

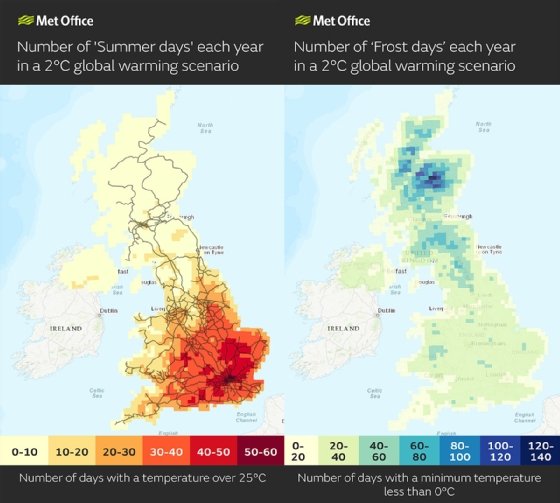

“The most detailed climate projections reveal a greater chance of warmer, wetter winters and hotter, drier summers and these help users plan and prepare for extreme weather, climate change and the reporting which new regulations, linked to climate change, will require.”

Stephen Belcher, chief of science and technology at the Met Office, added: “Human-induced climate change is having more and more impact on our lives, and it is crucial that new technologies, such as data integration tools, are harnessed to make sure the insights from science are getting into the hands of people who make decisions.”

During a pilot phase of the portal, which ran for 12 months, 4,000 users accessed the data. These included staff from the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and Forestry and Land Scotland, the organisation responsible for managing Scotland’s national forest estate, owned by the Scottish government.

Alan Gale, adaption and resilience manager for Forestry and Land Scotland, said: “Organisations like ours rely on authoritative and easy to access information for climate change decision-making, in land planning and management.

“The innovative approach being taken by the Met Office portal makes important climate data available to a broader range of users and, critically, lets us understand the local and regional climate differences at a glance.

“Predicting future climate is particularly important in forestry, given the long time scales involved – trees we plant today will still be growing in the 2050s and 2080s, for example.”

“Historically, climate science has defined the problem, now it’s moving to help with the solution”

Jason Lowe, Met Office

Emma Teuten, lead GIS analyst at RSPB Scotland, added: “The portal makes working with climate data faster and more accurate and saves months of development time when trying to understand the impact of climate change on specific sites in Scotland.

“We already use Esri’s GIS extensively and the new Met Office portal eliminates the time-consuming data conversion previously required as the data is now in ready-to-use geospatial formats.”

The Met Office expects the transport industry to be a big beneficiary of the portal, citing the fact that days above 25°C can indicate when trains could be disrupted due to overheating of railway infrastructure. Similarly, below-zero temperatures can indicate transport disruption and increased energy demand for heating.

The organisation also expects the portal to help organisations start their response to regulatory climate reporting such as TCFD (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures).

The main users of the new portal are expected to be within government, insurance, transport, energy, land use, urban planning and healthcare.

In an interview with Computer Weekly, the Met Office’s Lowe said he foresees the portal seeding a wide range of societal benefits as it – and the services around it – develop.

“One of the ways that we work increasingly in climate science is through co-development. We want the views of people who will be working with data, with our tools to help us with design,” he said.

“We have a relationship with Esri. We wanted to do something together. But then we also wanted to get user feedback. So, over the 12 months that the beta was out, we had users logging on, downloading data, combining it with their own data, and then feeding that information back to us as part of the process.”

Lowe said there had been nothing like the portal previously at the Met Office: “Part of what the Met Office does is produce a national set of climate scenarios to help people plan. UKCP18 was the most recent data set. It’s ‘18’, because that’s when we started releasing the data, but we’ve regularly added updates and extra parts. But that data was difficult to access. At the same time, we were thinking more generally about our climate services and how we could amplify reach using partners.”

Over to the users

Lowe said the Met Office’s climate models encompass a variety of future path possibilities, and that future usage is also elastic.

“We run a range of alternative futures through our climate models because we don’t know how many emissions there will be. In terms of usage, I end talks by saying to users: ‘It’s down to your imagination’,” he said.

“It could be spatial planning for cities, it could be siting of renewable power generation. It could be thinking about health care, and how where and when people might be affected by climate change. It could be about crops, and what you might be able to grow in particular parts of the country. We’re not expert in any of those sectors. But we want to bring the climate expertise in an accessible way.”

Lowe gives an example from his academic work as professor at the Priestley International Centre for Climate at the University of Leeds.

“One of the projects I work on [there] is analytics for the finance sector. We’ve learned that the finance sector is short of easy ways of visualising what’s happening spatially. And they have the problem of bringing climate data together with their own exposure data, and vulnerability curves,” he said.

“There are some tools out there, but they don’t have the breadth of data that we have. Imagine an insurance company or a pension company wanting to be able to access the spatial data for the assets in which they’re invested, or a bank thinking about where their mortgage burdens lie.

“Are they overexposed to the coast, for instance? Maybe they want to look at sea-level rise. Or the telecoms sector, with datacentres dotted around the country. We’ve all seen, I think, over the past two or three years, datacentres being affected by extreme weather.

“From my perspective, this is at a really early stage, there’s so much more climate data that we want to get out to more people. Our overall vision is to help people stay safe and thrive. This is a real practical way they can do that. I see this as the beginning of the journey of getting the [climate] data out to more people. And as we learn about what people are doing with it, I think this will help us understand what the next set of data to put out might be.

“One of the really exciting opportunities is to deliver services around the data portal. Some of those might come from the Met Office, but we also hope there’ll be an entire ecosystem. For us, it’s all about moving from defining climate change is a problem to helping with the solution. We want to help with planning for the future.”

Read more about climate change data

- UK satellite data to spearhead fight against climate change.

- Geospatial data a key means of combating climate change.

- AI and climate change: The mixed impact of machine learning.