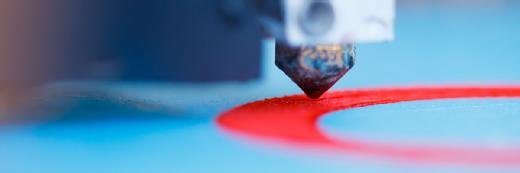

nikkytok - Fotolia

How 3D printing is growing one step at a time

We speak to a 3D printing firm that has expanded the reach of the technology by providing hardware and design software for customised insoles

MarketsandMarkets forecast recently that the global 3D printing market will grow by 22.5% a year, rising from $12.6bn in 2021 to $34.8bn by 2026. The technology’s usefulness was demonstrated during the pandemic, when 3D printing enabled companies to print parts for personal protection equipment (PPE).

According to MarketsandMarkets, the industrial manufacturing sector is moving from a prototype phase of 3D printing adoption to developing final products. For instance, 3D printers enable organisations in various industries to create custom, low-volume tooling and fixtures at a lower cost than traditional methods. MarketsandMarkets said small manufacturers get the same benefit with a 3D printer as Tier 1 global manufacturers.

Belgian 3D printing firm Materialise is one of the companies that has evolved its products and services to extend the reach of 3D printing.

Bart van der Schueren, chief technology officer (CTO) at Materialise, said: “When we started in 1990, we acquired a printer to develop services for the Belgian market but, fairly rapidly, we found there was a lack of 3D data. 3D CAD [computer-aided design] was non-existent.”

Drawings were often computerised hand drawings, he said. “What was missing was an easy way to get the data in a completely digital form – otherwise, it is impossible to print.”

Materialise began developing small tools for internal use to convert existing data for its industrial customers. It also began looking at medical imaging. “With 3D printing, we can customise a product to an individual,” said van der Schueren.

The company started producing 3D dental implants, and later expanded into knee surgery, providing a customised template using a patient’s anatomy. “Today, we provide knee implants for 56,000 patients a year,” said said van der Schueren.

In October 2020, Materialise moved into a new product category, acquiring RSscan dynamic foot measurement technology and the Phits personalised insole product line, as worn by London Marathon champion Paula Radcliffe.

According to van der Schueren, 20% of people are not wearing properly fitted footwear. This can lead to knee, hip and back problems. Applying similar techniques to personalised medical imaging 3D prints, van der Schueren said that, with adjusted footwear, it becomes possible to correct people’s gait and reduce the risk of injury.

The company has combined advanced gait analysis technology from RSscan with its 3D printing capabilities. This creates what Materialise describes as a “three-stage workflow”, enabling foot experts to design the most suitable orthotics more efficiently and accurately.

In the initial phase, Materialise Phits Suite helps foot experts scan and measure a patient’s data by using high-quality footscan pressure plates and 3D scanners. Next, the footscan software automates the insole design and provides science-based recommendations with a manual expert input option. Lastly, the foot expert sends the generated insole design through a cloud portal to the Materialise production facility. Within days, custom 3D printed orthotics are delivered to the practice and, ultimately, to the patient.

The company has worked with Gait and Motion Technology to offer 3D printed Phits insoles. Through a network of clinics, it provides the RSscan 3D foot scanner and accompanying software for podiatrists. During a consultation, a patient is asked to walk along the RSscan pressure plate a number of times. The matrix of sensors on the pressure plate takes measurements at various points on the foot.

“We developed tools to translate these pressure measurements into a gait analysis,” said van der Schueren, adding that this could then be used to 3D print a custom insole.

Looking at how the pressure plate operates, Scott Barton, director at Gait and Motion Technology, said: “There are 4,096 sensors, each measuring 5x7mm, recording at 300Hz per half-metre. This allows us to catch things fast and with more detail.”

The patient is asked to walk up and down the pressure plate six times, which provides enough data to analyse each pressure imprint. The data is then averaged and any bad data is removed, leaving a clear dataset for a podiatrist to use with the design software from RSscan to customise an insole to correct the patient’s gait.

The data is then encrypted to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation and pushed into the cloud, where it is added to a queue in the manufacturing system.

Read more about 3D printing

- Most manufacturers are still experimenting with 3D printing, but a growing number of companies have taken it a step further and are incorporating it into production processes.

- As the coronavirus outbreak disrupts supply chains, manufacturers may increasingly turn to 3D printing to move beyond prototyping and into producing quality parts.

Materialise is exploring how to use artificial intelligence (AI) to help in the development of customised insoles, said van der Schueren. “AI helps to learn from cases, but we think we have to bring in expert knowledge.”

He said AI could be used to compare different foot pressure profiles to identify patterns, adding that the corrections adopted are based on heuristics.

Ultra Trail world champion Tom Evans is one of the athletes who uses 3D printed Phits insoles fitted by Gait and Motion.

“The team from Gait and Motion Clinics have allowed me to be consistent,” he said. “I had really in-depth testing, followed by the delivery of my Phits insoles. It has been an amazing tool to keep me consistent in my big training blocks.”

Materialise’s strategy to develop a product suite to provide 3D printed orthotics and, through partnerships like the one with Gait and Motion Technology, offer a service to a wide customer base illustrates how 3D printing is becoming more mainstream.

For van der Schueren, insoles are about the right size to manufacture at scale using 3D printing.