Europol

Secrecy around EncroChat cryptophone hack breaches French constitution, court hears

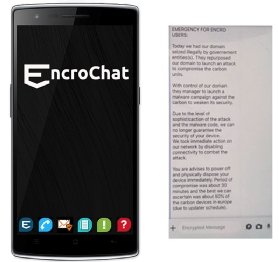

French lawyers claim that investigators are unlawfully withholding details of a cryptophone hacking operation in a case that could impact UK prosecutions

French prosecutors have unlawfully invoked “defence secrecy” to avoid disclosing information about the hacking operation into the EncroChat encrypted phone network, a court heard yesterday.

French police infiltrated the EncroChat encrypted phone network in April 2020, in an operation that has led to hundreds of arrests in the UK and Europe for offences including drugs, firearms and money laundering.

Lawyers told the Court of Appeal in Nancy that prosecutors were in breach of the French constitution and human rights law by refusing to disclose information to lawyers that they needed to defend their clients.

The legal challenge, which is expected to go to France’s Supreme Court and the European Court of Human Rights, is one of the first cases to question the lawfulness of the operation to infiltrate EncroChat in France.

If it succeeds, it is likely to raise questions about more than 250 prosecutions that are under way in the UK, which rely on text messages and photos harvested from EncroChat phones by the French gendarmerie.

Paris-based lawyers Robin Binsard and Guillame Martine, founders of French law firm Binsard Martine, argued during a two-and-a-half-hour hearing that defendants were being denied information that they needed for a fair trial.

Binsard told Computer Weekly: “We only have 1% of the documents related to EncroChat. They are keeping it secret in my opinion because they over-reached and did not respect the law.”

The lawyers told the court that French investigators had unlawfully intercepted tens of millions of “real-time” messages from tens of thousands of phones in a “massive data collection” exercise.

“We only have 1% of the documents related to EncroChat. They are keeping it secret in my opinion because they over-reached and did not respect the law”

Robin Binsard, Binsard Martine

They are also disputing the legality of orders made by the court in Lille against two internet services companies to prevent them taking any actions to disrupt the hacking operation.

Another court order that required datacentre company OVH to modify its network to enable the interception operation, was also in breach of French law, they said.

Gendarmes based at the C3N digital crime unit in Pointoise traced the servers used by the EncroChat phone network to OVH’s flagship datacentre in Roubaix following initial investigations in 2018.

They were able to covertly take copies of the servers and upload a software implant that was able to bypass encryption of the supposedly secure phones in April 2020.

A team of 60 officers captured 70 million messages from more than 32,000 phones in 121 countries within a month of the hacking, according to French legal documents (see box below).

The UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA), working with regional organised crime units and regional police forces, has made more than 1,550 arrests in the UK based on EncroChat evidence. Hundreds of people have also been arrested in the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Germany and other countries.

Forensic experts in the UK have argued that the French gendarmerie’s refusal to release information on the hacking has led to an evidential “black hole” that has broken long-established principles which ensure that evidence is properly acquired and secured before being used in legal cases.

Defence secrecy

The lawyers told Martine Escolano, president of the Chamber of Investigation, that they had received almost no information from prosecutors about the hacking operation.

“The absence of any criteria necessary for recourse to defence secrecy in matters of computer data capture seriously and manifestly infringes the rights of the defence,” they said in legal submissions.

“The status quo is unacceptable. Recourse to this secrecy affects the rights of the defence with particular gravity, without the slightest safeguards or checks and balances.”

Under French law, prosecutors are required to provide an explanatory note about the hacking technique used and the progress of the operation.

They are also required to provide a certificate of authenticity for the data used in evidence, but neither has been provided, the court heard.

French court documents reveal ‘real-time’ data capture

Extract from French court document:

“All data captured after installing the capture tool is assigned the time zone configured on the phone. These are so-called ‘real-time’ data.

“For the data presented before the installation of the capture tool, the time zone is not known. Some data are timestamped according to the parameters of the telephone and some others do not present a timestamp, this latter one not being known. This is the so-called ‘old’ data which was already recorded on the telephone.

“Note that it sometimes happens that the capture tool stops sending for a period of time. When the capture is resumed, the data sent and received by the telephone during this period then arrive on our server in the form of so-called ‘previous’ data, and therefore without a known time zone.”

“The investigators seem to have refrained from establishing any description of the technique actually used,” said the lawyers. “On the contrary, they felt they could evade this obligation by the sole mention of national defence secrecy.”

Binsard said that under Article 16 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (DDHC), every citizen has a right to a fair trial and to access the evidence used against them.

But defence lawyers and judicial investigators are unable to verify the reliability and authenticity of EncroChat messages captured by the French authorities, he said.

The live interception of EncroChat messages by gendarmes based at the C3N digital crime unit in Pointoise was in breach of article 706-102-1 of the French Code of Criminal Procedure, Binsard told the court.

“According to French law, they can only capture stored data, they cannot intercept live data,” he said. “There is not a law allowing them to do that. I think it is the reason why they kept everything under the secret of defence. The don’t want us to check live data because if there is live data, it is not legal.”

OVH ‘unlawfully’ ordered to re-route networks

Also in dispute is a court order that required the OVH datacentre in Roubaix to modify its networks to redirect data from EncroChat’s servers to a capture device set up by the French gendarmerie.

The Lille court ordered OVH not to take any action that would impact the network infrastructure, virtual machines and IP addresses associated with EncroChat, during the hacking operation.

Other court orders required domain name registrar Gandi SAS and hosting company DNS Made Easy not to take any action that could impact EncroChat’s Swiss-registered internet domains, during the hacking operation.

French investigators told the court: “It was necessary to put in place a certain number of technical measures intended to ensure that the capture operation was not neutralised by a change of configuration.”

Although French law allows the covert collection of data, it does not permit “blocking” or “modification orders”, the court heard, making the operation unlawful.

Mass and indiscriminate surveillance

Within a month of the implant going live, C3N had identified 380 EncroChat phones in French territory, of which 242 were linked to offences including drugs, money laundering and firearms.

But investigators were unable to link the remaining 138 phones in French territory to criminal activity, raising questions over whether C3N was right in law to harvest data from all EncroChat phones.

Binsard told the court that the surveillance operation went beyond the legal authority granted by the court in Lille, and amounted to “mass indiscriminate surveillance”.

Speaking after the hearing, he said: “They just catch everything without any discrimination. They catch the data from people without any link in any criminality, they catch everything. And this is not allowed by the law.”

The Irish connection

The gendermarie investigation, which was overseen by judicial police officer, adjutant Jeremy Decou, identified people at a high level in the EncroChat structure located in Canada, court documents reveal.

Customers were able to buy the phones using cryptocurrency from resellers who provided an “after-sales service” by helping customers to use their phones and passing on information from higher levels of the organisation.

EncroChat phones were distributed in France by a man of Irish descent who used the EncroChat handle “Leftbay”. The man, who is believed to have connections with Dublin, took instructions from “Shamrock”.

The documents reveal that the infiltration operation caused a network problem that affected EncroChat customers for several hours. One reseller estimated that 10% of EncroChat users were affected by the outage at OVH.

Another intercepted message showed that a reseller had warned phone users to be discreet in relation to the police. “It is therefore likely that the people at the highest level of the EncroChat organisation have knowledge of the criminal use that is made of their encrypted communication tool,” said investigators.

Breach of constitution

Speaking after the hearing, Binsard said the laws used by the French prosecutors to permit defence secrecy were in breach of the French constitution.

There are no impartial judges to control the use of defence secrecy, he said, and without that oversight, the law is not constitutional.

Binsard said French investigators had failed to certify the authenticity of the messages harvested from EncroChat, in breach of French law.

“They did not certify anything,” he added. “We cannot trust their investigation without this certification. We think the interception operation is illegal and that is why they want to hide everything.”

By carrying out massive data collection involving tens of thousands of mobile phones and tens of millions of messages, the investigators went beyond the framework set by a judge at the Lille court, he said.

“We criticise the point that they catch 100% of the users of this application,” said Binsard. “It is not allowed by French law. It is not allowed by the French constitution and it is a huge violation of the charter for human rights.”

Binsard said he was pessimistic about winning in the Appeal Court because EncroChat had become politicised with over 100 EncroChat prosecutions under way in France and more than 1,000 worldwide.

He said he would take the case to the French Supreme Court and to the European Court of Human Rights, adding: “EncroChat hacking is obviously illegal.”

The court decided that the case could go ahead yesterday despite objections from the French public prosecutor, who requested more time to prepare.

The public prosecutor told the court in a brief presentation that users of EncroChat phones were involved in illegal activities such as murder and drug dealing.

Read more about EncroChat

- Lord David Anderson QC warned prosecutors that there were formidable arguments against the lawfulness of a police operation to infiltrate the encrypted phone network, EncroChat

- French lawyers are challenging the legality of a French police operation to harvest tens of thousands of messages from the EncroChat encrypted phone network in a move that could overturn criminal prosecutions in the UK

- The Dutch Public Prosecution Service claims Britain has damaged confidence by disclosing details of an international investigation into the EncroChat encrypted phone network to the courts

- Lawyers claim that public interest immunity certificates may have been used to withhold information on UK intelligence agencies’ ability to decrypt encrypted communications

- Court hearings precipitated by police cracking the EncroChat secure mobile phone network have been delayed after defence lawyers request further disclosures on police decryption capabilities.

- Cops take out encrypted comms to disrupt organised crime: In July 2020, after French and Dutch authorities had gained access to the encrypted EncroChat network, the NCA and its counterparts worked to disrupt the serious and organised criminal networks using the platform.

- Appeal court finds ‘digital phone tapping’ admissible in criminal trials: On 6 February 2021, judges decided that, despite UK law prohibiting law enforcement agencies from using evidence obtained from interception in criminal trials, communications collected by French and Dutch police from EncroChat using software “implants” were admissible evidence in British courts.

- Belgian police raid 200 premises in drug operation linked to breach of encrypted phone network: On 9 March 2021, Belgian police raided 200 premises after another encrypted phone network with parallels to EncroChat, Sky ECC, was compromised, in what prosecutors described as one of the biggest police operations conducted in the country.

- Arrest warrants issued for Canadians behind Sky ECC cryptophone network used by organised crime: Following the international police operation to penetrate the Sky ECC network and harvest “hundreds of millions” of messages, a federal grand jury in the US indicted Sky Global’s Canadian CEO, Jean-François Eap, along with former phone distributor Thomas Herman, for racketeering and knowingly facilitating the import and distribution of illegal drugs through the sale of encrypted communications devices.

- Judges refuse EncroChat defendants’ appeal to Supreme Court: In early March, judges refused defendants leave to challenge the admissibility in UK courts of message communications collected by French cyber police from the encrypted phone network EncroChat. Computer forensic experts working on EncroChat cases said that decision should trigger a wider review of the “far-reaching effects” the legal decision by the Court of Appeal would have on the role of communications interception in future cases.

- UK courts face evidence ‘black hole’ over police EncroChat mass hacking: Forensic experts say that French investigators have refused to disclose how they downloaded millions of messages from the supposedly secure EncroChat cryptophone network used by organised criminals – leaving UK courts to grapple with a forensic ‘black hole’ of evidence.