spainter_vfx - stock.adobe.com

Lenovo, top-of-the-world Chinese supercomputer supplier, sweeps all markets

Supercomputers are not just about computing power, they are a symbol of political ambition. Chinese supercomputer supplier Lenovo is now the dominant supplier across the world

China’s main supercomputer manufacturer, Lenovo, has now also become the world’s main supplier of supercomputers. The company’s most extraordinary success is in the heartland of its keenest rivals in the US.

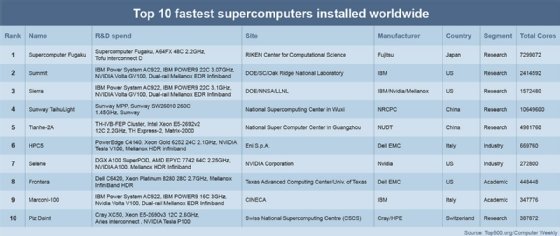

In the Top 500 list for June 2020, China is shown with a home installed base of 228 machines, whereas 20 years ago, in 2000, the country had just two of the top 500 machines installed. In comparison, the US had 258 machines in place 20 years ago, now it has just 117 supercomputers – of which 44, or 38%, are Chinese Lenovo machines.

And to further hammer home China’s success, not a single one of the country’s own huge installed base of 228 machines is an American machine – there are no Crays, no IBMs, no Dells. Plenty of American chips, but no American supplier presence.

This is the result of an embargo on the supply of supercomputers to China by the US, started in 1988/1989. It is an oft-repeated truism that all embargos do is force your adversary to innovate. There can have been few such formal or dramatic proofs of this principle in modern history as is the rise to dominance in this strategic market of China and the Lenovo company.

Huawei joins supercomputer race

And China’s success goes further, much further. Down at the bottom end of the list of China’s domestic installations are two new machines from Huawei – one at number 288 and another at 493. The entry of Huawei, primarily a telecoms supplier, into this market gives China five major mass producers of supercomputers – Lenovo, Sugon, Inspur and Think System, with Huawei bringing up the rear. With two machines now installed in Germany, Huawei has gone from home to export in one short step.

But Lenovo, apart from becoming the major single supplier of mid- and high-range supercomputers in the US, has also cleared two European markets of all other competition. Ireland, with 14 supercomputers and ranked seventh in the world league, has only Lenovo machines, all 14 of them with unnamed “software companies”. These are assumed to be the American internet giants Google, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft crowding Dublin with jobs, as the UK bales out of the European Union.

Germany, perhaps partly due to the death in 2014 of professor Hans Meyer, its leading supercomputer expert, now has a mere 16 machines installed and seems all but out of the supercomputer race.

The Netherlands, the world’s sixth ranked supercomputer power – one ahead of Ireland with 15 supercomputers – has only Lenovo machines. Again, this is an extraordinary clearing of a whole market, replacing the earlier suppliers, Cray, Dell and IBM, with just one supplier, Lenovo.

Fugaku: The fastest supercomputer on earth

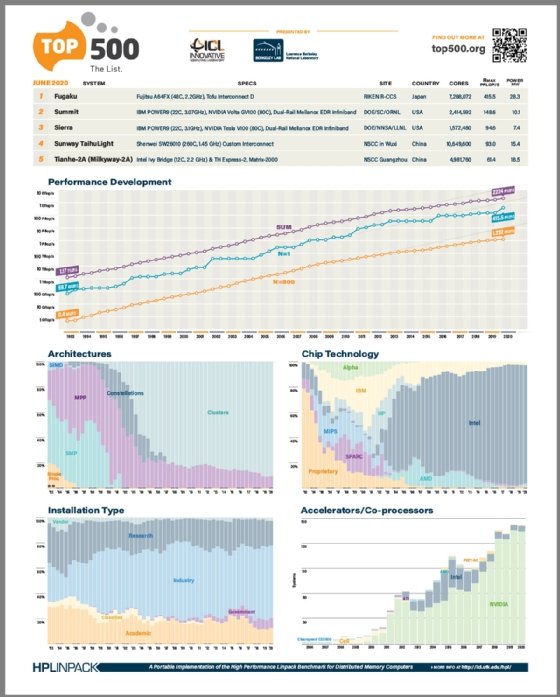

This June, the top machine in the world, churning over at 415.53 quadrillion floating points per second (FLOPS), is a Japanese machine called Fugaku.

It was built by Fujitsu and the Riken research laboratory in Kobe, Japan. It took six years to construct, at a cost of $1.2bn, but put Japan back in the top slot after an 11-year gap. That, however, is the least important part of the story. The Fugaku is more than 2.8 times faster than the number two machine in the world – the IBM Summit at the US Department of Energy’s National Laboratory in Oak Ridge in Tennessee.

Many people raved over the extreme processing power of Fugaku, but missed two critical facts. In certain situations, Fugaku hits an exaflop – a quadrillion quadrillion floating points operations per second – a goal no one was expected to hit until late 2021 or early 2022. The second is the yawning gap between the top two machines.

China tops list of supercomputers

In the top 10 of the June 2020 Top 500 list of supercomputers, China has two machines, at number four and number five, but in 2015, just five years ago, China topped the list of the fastest devices.

With the next speed goal in this field set at an exaflop – or 10 to the 18th power FLOPS – and with the Fugaku doing an exaflop in some applications, and being 2.8 times faster than the number two machine – the IBM summit at the US National Laboratory in Tennessee – the race has hotted up enormously. But what is the race? A race to build the fastest machine on Earth? Or a race to become the world’s top supplier of top-end supercomputers?

In this year’s Top 500 list, the UK, which has never featured big in supercomputing, slid a further rank in the listings of installed Top 500 machines to number nine, behind Canada at eight and Ireland at number seven. The UK’s biggest supercomputer, a £100m Cray Research machine at the Met Office in Exeter, while one of the biggest devices in weather forecasting worldwide, remains at number 33 in the long list of the world’s big machines.

UK to spend £83m a year on supercomputers

Over the next 10 years, the UK plans to spend over £830m, mainly on the Met Office machine in Exeter. That is a mere £83m a year, which may buy a mid-range Lenovo in a year or two, but not much else.

Met Office director Penny Enderby said: “This [£830m] investment will ultimately provide earlier, more accurate warning of severe weather, the information needed to build a more resilient world in a changing climate, and help support the transition to a low-carbon economy across the UK.”

As a result, detailed weather predictions for the UK now take place every hour instead of every three hours, providing crucial and timely updates when extreme weather is approaching.

It cost $1.2bn to get to the top slot in this year’s derby, according to estimates by Computer Weekly. Two years ago, the UK Met Office Cray machine cost £100m. Pricing will certainly have had a good deal to do with the 100% capture of the Irish and Dutch markets by Lenovo, but pricing remains a huge secret in this key part of the computer market. Our estimate is that a mid-range Lenovo machine, installed, will set a company back between £5m and £10m – cheap at half the price, it appears.