Warakorn - Fotolia

Freelancers hold generally positive attitudes towards gig economy

Report finds that digital labour-sharing platforms are increasingly popular among freelancers

Freelancers in the so-called gig economy are increasingly turning to digital labour-sharing platforms because of the autonomy and flexibility they allow, with 45% of gig workers saying the independence provided by these platforms is preferable to full-time salaried work.

A report produced as part of the BCG Henderson Institute’s Future of Work project, titled The new freelancers: Tapping talent in the gig economy, suggests governments and employers need to take a more nuanced view of the gig economy.

The study is based on a separate survey by the BCG Henderson Institute, the Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, carried out with support of Research Now SSI.

“There’s always this standard narrative of technological disruption – the highly qualified are able to adapt, but broad parts of the workforce might not be able to,” said Judith Wallenstein, senior partner and managing director of BCG Henderson in Europe and one of the report’s authors.

“We wanted to find out if that narrative of the business for franchise Uber drivers and people who face Victorian-era type exploitation [for example] was true, and if people really do like these kinds of jobs.”

Gig workers seek flexibility

According to the report, most freelancers did not choose gig work for lack of better options and, for many, gig platforms fulfil preferences for greater autonomy and flexibility in both their work and private lives.

“The most surprising thing was when we asked them what their ideal future was – such as, ‘Would you want to go, or go back, to full-time, salaried employment?’ – most of them responded with, ‘No’,” said Wallenstein.

Compared with 20% of those surveyed who said they would prefer full-time, salaried work, 45% said they would choose to remain independent.

“The elements of self-directed work – the ability to choose, the flexibility, the ability to combine it with other activities and commitments they might have – ranked very highly,” said Wallenstein.

However, the report also found that gig workers are not confined to the traditionally freelance-heavy sectors of IT and transportation. “Digital freelancing has emerged as a significant source of primary and secondary employment in all major industries, giving virtually all companies access to new freelancers,” it said.

Not all gig work is poorly paid

The report went on to say that the proliferation of gig work across industries challenges the perception that the gig economy is dominated by poorly paid workers.

“Low-skill, low-wage freelance tasks accounted for only about half of the freelance work sourced through platforms. Much of the remainder comprised higher-skilled, higher-paid work, such as software development and design,” it said.

It is important to note, however, that gig platforms differ wildly from one another in a number of meaningful ways. For example, a platform that acts as a middleman between an employer and a worker, where individual freelancers and employers can negotiate terms, is very different to a platform that directly contracts the worker or assigns them customers.

“I think that makes a big difference,” said Andy Chamberlain, deputy director of policy at the Association of Independent Professionals and the Self-Employed (IPSE).

“If the platform itself is engaging the person, offering some sort of terms between the platform and the individual, it changes to simply being a match-making service, so it’s all about how you negotiate with the enterprise – and if the platform is simply a facilitator to that negotiation, that’s very different.”

The devil in the detail

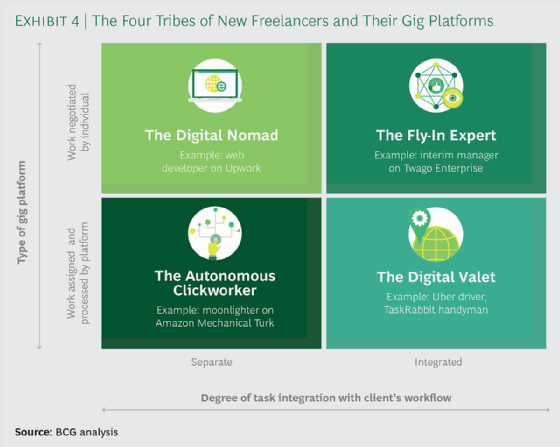

In an attempt to deal with the structural discrepancies between digital gig platforms, the report also identified four new freelancer “tribes” based on the type of platform they work on and the degree to which they are integrated into the client’s workflow.

“We realised that each of those segments works in a different way, and that people who felt they could negotiate their work, set their price and pick what they were doing – regardless of if they were doing it very remotely or if they were flying in to be integrated with a client’s teams – were obviously valuing the autonomy a lot more highly versus people who don’t have that,” said Wallenstein. “Click-workers and Uber drivers fall more into that [second] category.”

However, the BCG Henderson Institute’s segmentation came from additional interviews it held with freelancers, while the statistics in the report, including those about freelancer preferences, were based on the survey results which did not segment the freelancers in this manner. It is therefore difficult to distinguish what type of gig workers held positive or negative attitudes towards freelancing.

Despite this, the report suggested a consensus among business leaders that digital labour-sharing platforms would only become more pronounced.

Roughly 40% of respondents said they expected freelance workers to account for an increased share of their workforce in the next five years, while 50% agreed the corporate adoption of gig platforms would be a significant trend.

More freelance, more precarity?

With the number and importance of gig workers increasing, there is a risk that labour could become more precarious.

Antonio Aloisi, a teaching fellow in European Social Law at Bocconi University, has previously argued that mass take-up of labour-sharing platforms could increase productivity, but warned that employment could become fragmented into “hyper-temporary” jobs, known as micro-tasks, as a result.

“All these intermediaries recruit freelance or casual workers who are labelled as independent contractors, even though many indicators seem to reveal a disguised employment relationship. Uncertainty and insecurity are the price for extreme flexibility,” he wrote in 2016.

According to the most recent figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the current UK employment rate is at a high of 75.8%, with roughly 32 million people in work.

However, according to a 2016 analysis of official figures by labour market economist John Philpott, one in five workers – or 7.1 million – are facing precarious employment conditions that mean they could suddenly lose their work.

Further figures from the ONS show that 1.8 million (6% of the UK’s active workforce) are also on zero-hour contracts.

“I’m very worried about precarity in the workforce – I don’t deny that in any form. I just don’t believe that the gig economy will be a massive driving force behind this,” said Wallenstein.

The report found that in mature markets, such as the UK, US, Germany, Sweden and Spain, only 1% to 4% of workers cited gig platforms as their primary source of income. A further 3% to 10% reported using gig platforms as a secondary source of income.

“You see a slow and steady growth, but you don’t see a jump,” said Wallenstein. “There’s not a tonne of freedom to believe we will see exponential growth, and if you see how companies are using freelancers, I see as much reason to believe that companies will actually make bigger efforts to reach out to freelancers for expertise and talent reasons, rather than just cost arbitration reasons.”

Juliet Schor, a professor of sociology at Boston College who has been studying the sharing economy since 2010, wrote in 2014 that it was difficult to assess the impact of these new earning opportunities due to the fact that they are being introduced a time of high unemployment and rapid restructuring of the labour market.

“If the labour market continues to worsen for workers, their conditions will continue to erode, and it will not be because of sharing opportunities. Alternatively, if labour markets improve, sharers can demand more of the platforms because they have better alternatives,” said Schor.

“The two effects will work in opposite directions – with destruction of demand for legacy businesses and growth for sharing companies.”

On the issue of precarity, Chamberlain added: “That’s not to say it’s completely free of imperfections, but overall we do think it’s a positive thing for the economy and for individuals and businesses to have these tools, which are basically just platforms offering different types of work.”

Regulating precarity

According to Wallenstein, in terms of regulating to protect workers from greater precarity, the industry that they work in and the type of work they are doing, regardless of skill level, matters.

“You can argue that at the high-skill end of the spectrum, one shouldn’t worry too much because those are very similar to a lot of the liberal professions that have been around for decades,” said Wallenstein.

“Digital platforms give them further reach with what they’re doing, but it doesn’t change their way of working, their income structure or the way they purchase health insurance, and so on.

“We have to look carefully at each of the [worker] segments [when it comes to precarity and labour regulation] – where do we specifically have low-skilled freelance workers who don’t have the negotiation power on which clients they take, that are in a way fully dependent on the platform for this, and are the conditions under which they are working in line with the rest of the labour laws in their respective country?”

Read more about technology and the workforce

- Organisations will have to find new ways of reskilling their workforce as they get to grips with artificial intelligence and other digital technologies.

- Matthew Taylor’s review on the gig economy calls on government to invest in digital technology to support self-employed people.

- India maybe losing its pre-eminence as the IT outsourcing venue of choice – we look at five outsourcing venues to watch.