Big data journalism exposes offshore tax dodgers

How journalists harnessed big data to challenge offshore financial secrecy

The offshore financial world will have to transform as the result of the processing and reporting of Offshore Leaks – the largest quantity of confidential data leaked to the press to date – by an international group of journalists. [1]

Offshore Leaks, the largest ever big data project tackled by journalists, required a combination of programming and computer forensic skills, sophisticated free text retrieval software, IT security, and collaboration between more than 100 journalists worldwide.

The data trail began in 2010 in Australia. Following investigations of a decade-long international fraud involving a fake fuel booster additive product, sources gave Sydney journalist Gerard Ryle a hard drive containing 260GB of corporate files and personal information from offshore tax havens. [2]

The data on the hard drive did not just help reveal how more than $100m looted by Firepower fraudsters was recycled through tax havens, but also included the identities of many of the owners and founders of more than 100,000 companies and trusts set up in the British Virgin Islands and other secretive offshore centres in the Caribbean and Pacific.

Over half of the wealthy individuals in the data, later analyses found, were Chinese and other Asians, recycling their burgeoning wealth offshore and then back, unattributably, into their nation’s businesses and property. The next largest group was Russians or CIS nationals, who similarly started exporting capital after the dissolution of the Soviet state.

Bagged a job

The year after he was given the data, the promise of what was on the hard drive smoothed Ryle's path to a new job as director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), a Washington-based publication group run by the not-for-profit Center for Public Integrity.

Processing and publishing the leaked data brought to the US from Australia took over 18 months to bring to fruition, and is still continuing. As the largest ever big data project tackled by journalists, the investigation faced technical problems and errors from the start, took blind alleys, and encountered problems in collaboration, as well as pioneering effective new methods. Eventually, it produced major results.

The first wave of reporting of Offshore Leaks stories began in the UK's Guardian in November 2012, followed by a global relaunch in April 2013. The stories had a direct impact on preparations for this year’s G8 summit in Lough Erne, Northern Ireland, which called for offshore company records to be opened up “to fight the scourge of tax evasion”. [3] David Cameron asked for offshore company records to be published in normal registers.

The Offshore Leaks project was “the most significant trigger behind these developments", EU tax commissioner Algirdas Semeta said before the summit in June .[4]

"It … created visibility of the issue and … has triggered political recognition of the amplitude of the problem," he said. "We're not talking about €100bn or €200bn here, but about €1tn," he added – the amount of revenue EU nations are estimated to lose every year.

The analyses and reports embarrassed France’s president François Hollande, whose campaign fundraiser had not disclosed his use of offshore accounts. Another article prompted the resignation of the CEO of Austria's Raiffeisen Bank International. The same and similar stories were repeated in countries from the Philippines to South Korea. A Mongolian minister resigned after his offshore accounts were revealed. The European Union has asked ICIJ for access to the data on EU citizens.

Leaks go on getting bigger

Collections of corporate financial data have been sold in the past decade to tax authorities in the US and elsewhere. Large datasets have been passed to journalists before, the most famous being the WikiLeaks collection of military reports and US diplomatic cables published in 2010. Although it may not have as far-reaching consequences, the Offshore Leaks data cache is 160 times bigger than the 250,000 US diplomatic cables published by WikiLeaks.

The alleged WikiLeaker, US marine Bradley Manning, is currently on trial for allegedly “helping the enemy”. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange remains in his second year of effective house arrest in the Ecuadorean embassy in London. Hollywood’s feature film version of the WikiLeaks story, Fifth Estate, will launch this October.

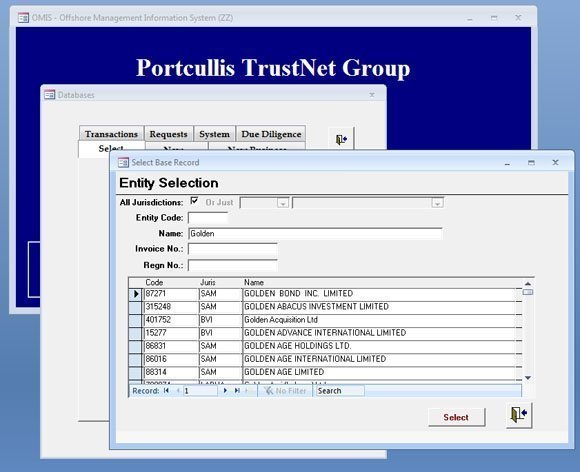

The Offshore Management Information System (OMIS) used to manage tax haven clients in the British Virgin Islands

The Offshore Leaks data was far more complex than the rigidly structured and numbered US State Department cables. The cables were identified by subject and writer, making it relatively easy for journalists and programmers to sort by country and topic. Helpfully, as the cables showed, US diplomats were taught to write clearly, spell correctly, and knew what countries they were referring to.

The Offshore Leaks data was, in contrast, a mishmash. Emails have no implicit structure, meaning that finding relevant information in huge Outlook containers of tens of thousands of stored mails was a search for needles in haystacks.

Several large, structured relational databases of offshore clients and their companies were included in the leaks, but were found on examination to be badly programmed and constructed, creating major problems using and analysing the data.

Technical challenges

ICIJ director Gerard Ryle freely admits that he knew nothing about data or programming when his project began. He was also anxious that the clients and the companies whose data had been leaked to him might learn of the data loss, and use legal tactics to halt or block the Offshore Leaks project before it got off the ground. Secrecy seemed essential.

In the first few months of examining the data, work went backwards. There was substantial structured data in the collection, including large SQL and Access databases of offshore companies and their managers. These databases were the key to who and what was in the data. Unfortunately, for the progress of the project, a data specialist “assisted” by transforming the relationship structures of the key databases into flat Microsoft Excel tables for distribution.

The effect of this was that while participating journalists then had lists of people, and separate lists of companies without having to master SQL, the information about who was linked to what was lost to view, unless knitted together by hand – an agonising and unnecessary process.

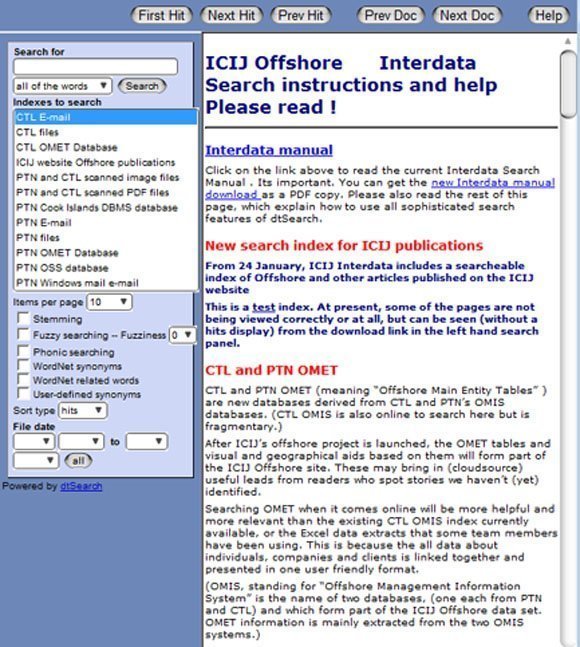

Until a specialised e-discovery software company, Australia’s Nuix pty, gifted ICIJ the use of its high-end text retrieval software, there was no way to search the unstructured data, which was not held in databases. This had to be indexed. We later added a second and less sophisticated, but generally faster text search program, dtSearch.

Although unfamiliar or unknown even to most current data journalists, tools such as Nuix and i2, as well as cheaper alternatives, are widely used by major law firms for researching in case papers, and by law enforcement and investigating agencies. A project of the nature of Offshore Leaks needed to use free text search tools to make any progress at all. Random searches could be attempted, but would inevitably miss most of what was there.

Six months passed before the structured company databases were rebuilt and made operational for team members. Much of the information from these databases has since been made public, ahead of the June G8 conference, and can now be searched by anyone. [5]

Communications difficulties and excessive security slowed down the project. At the outset, the ICIJ team was persuaded to use PGP to encrypt all communications. The complexities of using non-standard crypto tools across different platforms in different countries made large-scale data sharing impossible and limited what work could be done.

As a result, only one group, led by the Guardian's investigations editor David Leigh, published Offshore Leaks reports during 2012. Leigh and Guardian data specialist James Ball had previously pioneered the reporting of the WikiLeaks stories two years earlier.

A security reappraisal questioned the need to use high-level cryptography to hide from signals intelligence agencies such as the US National Security Agency (NSA) or Britain’s GCHQ. As national policy in each country opposed tax havens and evasion, the agencies' political masters were more likely to be in favour of the project than undermining it.

The project probably only needed protection from prying Chinese or Russian eyes, whose citizens formed the larger part of the data collection. The solution selected was to use standard bulletin board software, but to compel properly engineered SSL and forward secrecy. The bulletin board was not hosted on cloud servers but at a privately owned and secure datacentre in Germany.

| Software used for Offshore Leaks | ||

| Nuix | Nuix, Australia | Free text search and e-discovery |

| dtSearch | dtSearch, USA | Free text search and e-discovery |

| Interdata | Bespoke secure online search system for 260GB data set (Duncan Campbell and Matthew Fowler, UK) | |

| ICIJ Forum | Secure chat and file exchange (Sebastian Mondial, Germany) | |

| Public offshoreleaks database | Web platform to search and display graphical or tabular information about individuals and entities in structured data (Rigoberto Carvajal and Matthew Caruna Galizia, Costa Rica) | |

| “Carlita” | Bespoke software (written in Java and SQL) to cross-match and link names of individuals entered multiple times with multiple mis-spellings (Rigoberto Carvajal, Costa Rica) | |

| CountryScanner | Bespoke software (written in C##) to identify countries of residence (Matthew Fowler, UK) | |

| SQL and My SQL | Microsoft/open source | Relational databases |

| Talend | Open source | ETL (extract transform load) data integration tool |

| Microsoft IIS | Microsoft, USA | Internet server (Interdata) |

| Apache | Open source | Internet server (Offshoreleaks) |

Spreading the data

During 2012, a major issue was getting large selections of data securely to an ever-growing group of investigative journalists, who could then research and report the significance of their countries’ users of offshore companies.

The first approach to this, distributing and installing individual hard drives, was inevitably limited by travel costs and also entailed security risks. Large-scale expansion was not practicable in this way.

The second approach was to carry out searches and export files centrally, using the Dropbox cloud storage and sharing system. Other sharing systems would probably have worked as well. But before the end of 2012, this method was also clogged, because of the time taken to extract and load files. The only solution left was to expand the project to make the data searchable online.

We then created a search engine for the entire data in Offshore Leaks, using the web publishing version of dtSearch and a secure shell to control access to authorised users. Some of the group feared that this system would become vulnerable to attacks or attempts to break in. Other than the routine background scanning on the internet, there was no evidence that this happened.

Secure online search system, Interdata

As the project peaked this spring, more than 100 journalists were logging into a secure online search system, Interdata, to find and download relevant data in two million emails and a half a million other files.

Without this tool, and the ability it gave local journalists in more than 50 countries to get to the relevant data, the scale and impact of this big data project would not have been possible.

Less happily, the Offshore Leaks project shared with Wikileaks some controversy and difficulty, with some individuals pursuing private and divergent agendas, limiting the effect and value of collaborative work. This problem for quasi-voluntary organisations, as well as corporates, is unlikely to go away any time soon.

Looking back on a steep learning curve for many involved, it is apparent that the competent use of structured query language databases and well scoped free text searches should be mandatory for future big data journalism projects. Had they been introduced at the beginning, the project might have taken half the time, yet produced more results. The most obvious lesson learned is the need for training and experience. With dwindling resources, it may be difficult for many media organisations to rise to that challenge.

Investigative journalist Duncan Campbell was the data journalism manager for the ICIJ Offshore Leaks project.

Investigative journalist Duncan Campbell was the data journalism manager for the ICIJ Offshore Leaks project.

No easy answers from big data

By Craig Shaw

I became involved in Offshore Leaks having never previously been exposed to big data. My experience can be thought of as a young reporter’s baptism-by-fire – but then no other group of journalists has had to handle such a dirty, huge, unstructured haul of files.

The offshore networks of embezzling officials, known fraudsters, arms dealers and small-town businessmen and women looking to control how much tax they choose to pay did not jump out into neatly parceled stories. Analysing the data took much time, hard work and the right tools.

I found that with even a basic understanding of the text search tools Nuix and dtSearch, the data opened up, facilitating obsessive sessions of late-night digging.

In the beginning, everybody we brought in or helped went for “wish-listing” – inputting a list of sexy high-profile names that they hoped would score hits – and big stories. A few then became frustrated about the lack of obvious and easy targets, and walked away. Most stayed.

Wish-listing rarely works with big data leaks, we found. If the data did contain the elusive offshore companies of a Berlusconi or a Putin or an Ashcroft, simple name searches would not usually be expected to yield fruit. The accountants and agents who facilitate high-profile individuals’ use of offshore services are smart, deploying nominees and other tricks of their trades.

The offshore world thrives because its architects understand how to create layers of complexity. Employing nominee agents or nominee companies is an effective means to hide real beneficial owners. And when these nominee companies are incorporated in other far off jurisdictions behind yet more bogus agents, it creates near-impenetrable secrecy.

But it only takes a small spark to light the touch paper and find a trail to follow. One spark for us was the curious listing of two Australian Aids charities as beneficiaries of an offshore trust set up in the Cayman Islands.

The trust concerned, we learned, was not run by or known to the charities named. It was instead the offshore vehicle of a discredited US doctor, who managed investment accounts worth millions of dollars in the Cayman Islands and Swiss banks. It became a front-page newspaper report in Australia. It also led us to a well-known but unreported scam – using charities to conceal who really owns trust funds.

This revelation led enquiries to four UK charities who were the supposed beneficiaries of a £146m luxury property investment in London’s Belgravia, and for which the Royal Bank of Scotland lost millions of pounds before having to be bailed out. It became a Sunday Times front page story.

That investigation in turn led to a Marylebone-based law firm which had also utilised the good names of charities to obscure trusts on behalf of wealthy Italian families. That in turn was associated with the International Offshore Services Group, based in Ireland, whose 1,600 client companies have frequently been cited in court cases, including arms running and the disappearance of over $4bn from a Kazakh bank.

Like all big data, the offshore files provided only a window. Getting the best required accepting its limitations. The use of open sources – company registers, court records, press releases, and even social media – was as critical to unraveling the offshore world as the IT tools we deployed. That and old-fashioned hard work.

Craig Shaw is a freelance reporter working for Duncan Campbell and his company IPTV Ltd.

Craig Shaw is a freelance reporter working for Duncan Campbell and his company IPTV Ltd.

[1] https://twitter.com/#offshoreleaks, www.icij.org/offshore

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firepower_International

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/g8-lough-erne-declaration/g8-lough-erne-declaration-html-version

[4] http://euobserver.com/economic/120382

[5] offshoreleaks.icij.org

Read more on Data warehousing

-

![]()

Met Police spied on BBC journalists’ phone data for PSNI, MPs told

-

![]()

Over 40 journalists and lawyers submit evidence to PSNI surveillance inquiry

-

![]()

Detective reported journalist’s lawyers to regulator in ‘unlawful’ PSNI surveillance case

-

![]()

Police arrested journalists as part of surveillance operation to identify confidential sources