Photographee.eu - stock.adobe.co

UK sale of surveillance equipment to Macedonia raises questions over export licence policy

The UK approved an export licence for the sale of surveillance equipment to Macedonia – while the country was engaged in an illegal surveillance programme against its citizens. A senior minister was consulted on the decision

The UK government approved the export of controversial surveillance equipment to the Republic of Macedonia, despite concerns over the country’s human rights record, documents obtained by Computer Weekly show.

The Macedonian government that acquired the equipment subsequently collapsed after an outcry that followed revelations of widespread illegal surveillance of citizens.

Gamma International (UK) Limited, a company that specialises in exporting surveillance equipment, won approval to sell six surveillance devices, known as International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) catchers, in October 2012, while Macedonia was engaged in an illegal mass surveillance programme.

Macedonia’s former coalition government, led by Nikola Gruevski’s right-wing VMRO-DPMNE party, was ousted in December 2016 after leaked audio tapes showed the Macedonian secret services had illegally spied on the country’s citizens, including politicians, civil society activists and journalists, since at least 2011.

Between 2008 and early 2015, the Administration for Security and Counterintelligence illegally intercepted conversations from nearly 6,000 phone numbers affecting more than 20,000 individuals.

The public discontent that followed the revelations contributed to a change in leadership, when the VMRO-DPMNE lost public support and found itself unable to form a new government after more than a decade in power.

How the British sold surveillance equipment to Macedonia

Senior officers of the Macedonian UBK made a trip to London in 2010 and reportedly agreed the purchase of surveillance equipment from the British company Gamma International, part of the Gamma Group.

Emails from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), obtained by Computer Weekly, confirm that Macedonia bought “interception equipment from Gamma” the following year.

And in May 2012, the UK government approved an export licence to Gamma International to supply six sophisticated devices, called 3G-N 2F IMSI catchers, with a 3G Blind Call function.

David Lidington, the then minister for state for Europe and current secretary of state for justice, was consulted on the decision. He did not wish to comment when approached by Computer Weekly.

Gamma International

In 2015, the Canadian research group Citizen Lab found that another Gamma-marketed product, FinFisher, was used in Macedonia.

No export licence appears to have been issued for this specific software. One of the email conversations released by the FCO – dated 17 March 2016 – which refers to the UK's approval of an export licence for Gamma's IMSI catchers to Macedonia - states: “there were no other licences issued apart from one, which appears to be to enable export of goods under warranty/for repair”.

In 2011, The Guardian reported on Gamma offering spying equipment to Egypt’s regime. Media and privacy campaigners’ attention has been high ever since. More recently, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has found Gamma to be in breach of human rights guidelines – the first time in history this has occurred for a surveillance software company.

According to Gamma International’s UK filings, the company is currently 100% owned by Louthean John Alexander Nelson, born 1961, a British national who lives in Lebanon and works there as a security consultant. It is managed by two directors, Nelson himself and William Louthean Nelson, born 1932. The company is at present in poor financial health, having negative equity of £242,662. However, Offshore Leaks has shown Louthean John Alexander Nelson to be a shareholder in two British Virgin Islands companies.

Gamma International (UK) Limited did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

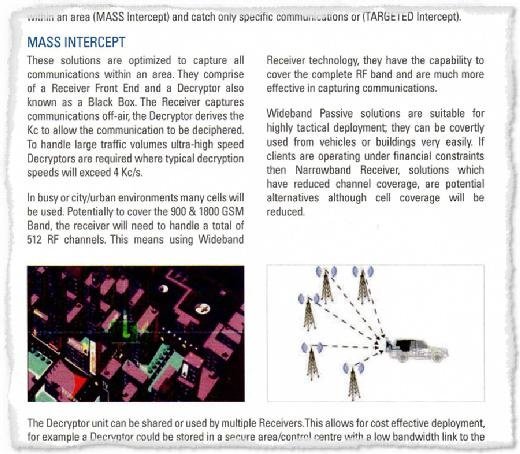

The IMSI catchers were capable of capturing and recording mobile phone voice calls, SMS messages and covertly recording details of mobile phone calls made within the range of their antennas – on a huge scale.

The customer was the Ministry of Interior (MOI) in Skopje, the government department responsible for the policing of organised crime, and the Security and Counterintelligence Administration (UBK), Macedonia’s equivalent to MI5. The UBK was later implicated in the surveillance scandal that shook the country from early 2015.

The Foreign Office’s Arms Export Policy Department (AEPD) and Human Rights and Democracy Department (HRRD), together with the British Embassy in Skopje, considered the human rights record of the Macedonia government before recommending approval for Gamma International’s export licence.

Surveillance equipment needed to tackle organised gangs

According to an internal report obtained by Computer Weekly, the Ministry of Interior intended to buy Gamma’s surveillance equipment for “geo-locating and tracking” the 3G mobile telephone traffic belonging to organised criminal gangs. “Organised crime remains a significant problem in Macedonia, and there is an operational need for the MOI to have the best equipment to combat it,” the FCO memo states.

The document shows that if the Foreign Office team did have concerns over illegal surveillance by the Macedonian government, they were allayed by the Macedonian Parliament’s introduction of legislative controls to limit telephone intercepts to organised crime cases, and discussions in the Macedonian Parliament to improve Parliamentary oversight of surveillance.

The report quoted heavily from the latest 2011 EU progress report on Macedonia, which noted that the Macedonian government had stepped up its supervision of the police, and that the Ministry of Interior had been willing “in several cases” to bring criminal cases against police officers involved in alleged criminal offences.

However, it failed to mention that the same 2011 EU progress report on Macedonia had raised doubts about the ability of the Macedonian government to carry out effective oversight of the country’s police and intelligence services.

The report states that the Macedonian Ministry of Interior unit “is yet to be transformed into an authority that is fully independent from the police with the ability to implement effective investigations”.

“Parliamentary oversight of intelligence and counter-intelligence services remains weak. In 2010, only one session of the Parliamentary Committee was convened. There is insufficient cooperation between the Parliamentary Committee and the Bureau for Security and Counterintelligence,” it said.

Covert mobile phone monitoring favoured by police forces

IMSI catchers are a favoured form of surveillance for police forces around the world because they do not require cooperation from mobile operators to monitor large numbers of mobile phones. They can be used to send automated messages to crowds during protests.

They gather data by conducting man-in-the-middle attacks against mobile phone users. The device pretends to be a cell tower and acts as a malicious relay for mobile phones in the area, which gives the IMSI operator the opportunity to eavesdrop on the network traffic.

They can be worn on the body or in a backpack to allow police to mix with crowds or protests, and can also be used in cars or mounted in fixed locations. The fixed devices have access to better power supplies, giving them greater range and capabilities.

Gamma International’s IMSI catchers are capable of capturing and recording mobile phone voice calls, SMS messages and covertly recording details of mobile phone calls made within the range of their antennas – on a huge scale

The range of IMSI catchers depends on the power available and the terrain of the area being monitored, but typically they can intercept calls anywhere from tens of metres to 1-2km. In “catch and release” mode, IMSI devices from some manufacturers can acquire metadata and location at a rate of “1,500 handsets per minute across five networks”.

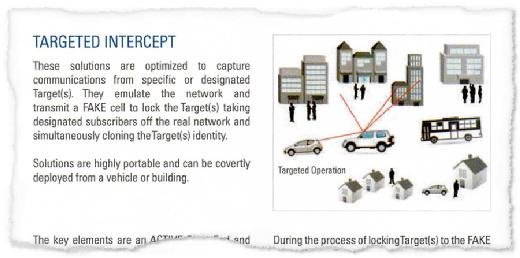

Gamma’s 3G IMSI catchers, whose specifications have been leaked online, allow the interception all voice calls and SMS messages either made or received. They can spoof the identity of a target phone to send SMS messages or make voice calls that appear to come from the person under surveillance.

They can block calls so they are not received by the target, and divert or edit SMS messages before they are received. The company’s 3G Blind Call capability ensures that the phone can transmit information to the catcher without the target being aware.

Gamma International’s catalogue shows the features of its IMSI catchers

According to its sales brochure, Gamma’s IMSI catchers are capable of hoovering up metadata, location and SMS data, and phone conversations at a rate of up to 20 simultaneous calls recorded per device.

UK government accused of short-sightedness

Privacy campaigners have accused the UK government of short-sightedness in approving the export licence.

“The UK government has consistently claimed that the current system of assessing licences is robust, but it’s clear here that it has failed to properly scrutinise the legal framework governing surveillance in Macedonia,” says Privacy International researcher Edin Omanovic.

“The use of IMSI catchers is considered so sensitive in the UK that the police refuse to comment on them. Yet the government has been licensing their export to dozens of destinations, including to countries with horrific human rights records where surveillance is routinely used to target activists, journalists and opposition members,” says Omanovic.

That the UK approved this licence to a department which appears to have been engaging in illegal wiretapping on a mass scale illustrates the huge risks involved and just how short-sighted and counter-productive this is.

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s assessment that Macedonia’s attempts to bring greater scrutiny to the UBK and stronger parliamentary scrutiny were to prove, at best, optimistic.

A legal expert told Computer Weekly: “Where there are more red flags, one would generally expect enhanced due diligence to be conducted in respect of licence applications. In the case of Gamma International, this may extend to factors such as Gamma’s track record and Macedonia’s questionable human rights record.”

Uranija Pirovska, who was the director of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights when the export licence was issued, says that in 2011 – the year before the UK government approved the export licence – there were already clear indications that Macedonians were living in a non-democratic regime.

She cites the brutal murder of a young man at the hands of former prime minister Gruevski’s bodyguards on the night of the 2011 elections, and the arrest of opposition politician Ljube Boskovski the day after. It also emerged that the Ministry of Interior had tried to cover up the involvement of Gruevski’s bodyguards in the 2011 murder.

When the leaked tapes came to surface in February 2015, Pirovska found she had been wiretapped since 2011. “We [activists and journalists] had the strong suspicion that we were being wiretapped back then, as you could hear that the phone conversation was not clean,” she says.

The tapes also exposed several high-profile corruption scandals that are being investigated by the Special Prosecution (SJO). Accusations include money laundering, irregularities in public procurement, the illegal demolition of buildings belonging to political opponents, electoral fraud and more. Five cases involve the former prime minister Gruevski himself.

Macedonia promises surveillance reforms

Macedonia’s new government, led by the Social Democrats, was formed in May 2017. A particular challenge for the new administration is to prevent illegal surveillance in the future.

The EU sponsored two investigations, led by former European Commission director Reinhard Priebe, to tackle systemic failures with the rule of law and widespread corruption in Macedonia. The two inquiries, known as the Priebe reports, were compiled in June 2015 and in September 2017 by a Senior Experts’ Group.

They place particular focus on ensuring proper oversight over the Bureau of Security and Counterintelligence (UBK) and strongly recommend that the direct access to technical equipment by UBK should be removed.

Responding to Computer Weekly, the Macedonian government affirmed its commitment to ensure this by following the recommendations set out in the Priebe reports. “Negative political influences have been removed, and the government is undertaking measures to strengthen the surveillance over the system for communication monitoring,” it says.

Pressure groups have argued that it should be a key priority for the current Macedonian government to ensure that the country’s intelligence agencies never again get direct access to telecommunications networks, to prevent such abuses from happening in the future. That work, says the Macedonian government, has yet to be completed.

Why the FCO recommended the export of phone surveillance equipment to Macedonia

Why did Macedonia need mobile phone surveillance equipment?

There was “an operational need” for the Ministry of Interior to have the best equipment to help combat organised crime, which remained a significant problem in Macedonia, according to a Foreign Office memo obtained by Computer Weekly.

“There have been recent high-profile killings in Macedonia, and an extensive effort was conducted to track perpetrators involving telephone intercepts of analysing the motives of the attack,” the memo says.

Police operations against toll booth operators and the arrests of large numbers of police officers in eastern Macedonia in early 2012 illustrate the challenges facing police in combating organised crime.

Did Macedonia have proper controls and oversight of state surveillance?

According to the UK government memo, in 2007/8 the Macedonian Parliament adopted legislative controls that would enable telephone intercepts only in cases of organised crime. Legislative proposals being discussed in Parliament aimed to remove the Minister of Interior’s role in making decisions on interception and to improve oversight.

What concerns were there about human rights in Macedonia?

The EU and the US have been placing pressure on Macedonia over human rights since the country’s independence in 1991, the Foreign Office memo reveals. The US had raised concerns in its latest human rights report about the high level of complaints over the excessive use of force by police and the potential for “police impunity”.

Non-governmental organisations and opposition parties had reported potential cases of arbitrary arrest or detention, and at least one instance of murder of a protester at the hands of the prime minister’s bodyguards. According to the EU’s annual progress report, corruption [in the police force] remained a serious problem and the oversight of the work of the police and intelligence services was too weak.

Where were the mitigating factors for the Foreign Office?

Despite complaints about excessive use of force by police in Macedonia, the FCO memo states that there had been no acts of unlawful or arbitrary killing. The Macedonian criminal code requires all warrants to be authorised by the investigative judge or a public prosecutor. “Of particular relevance to this licence request, the US report states that the government generally respects the prohibitions on arbitrary interference with privacy, family, home or correspondence.”

What about police corruption?

According to the EU’s annual progress report, cooperation between the Ministry of Justice and law enforcement needs to be strengthened, and the collection and processing of information on the extent and nature of corruption remains deficient. Corruption remains a serious problem, it says.

What were the mitigating factors for the Foreign Office?

According to the EU progress report, quoted by the FCO, the Ministry of Interior was “willing in several cases to bring criminal cases against police officers alleged to have been involved in criminal offences”. This was said to show that the Ministry of Interior had intensified its monitoring of police work.

The verdict

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s Arms Export Policy Department and the British Embassy in Skopje recommended that Gamma International (UK) Limited should receive a licence to export its “3G-N 2F IMSi catcher with 3G blind call” equipment to the Macedonian Ministry of Interior.

Sources: (i) redacted Foreign Office memo, export licence reference: SIE2012/006223, (ii) 2011 EU progress report on Macedonia, (iii) Uranija Pirovska, former director of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights