JRB - Fotolia

Interview: James Bamford on surveillance, Snowden and technology companies

Investigative journalist and documentary maker James Bamford was among the first to uncover the secrets of the US National Security Agency and its global surveillance

James Bamford has what he calls a love-hate relationship with America’s most secret intelligence agency. During more than 30 years of writing about the US National Security Agency (NSA) he has been threatened with prosecution, occasionally been praised for his work – but has mostly met with hostility. “It’s not a good relationship because they don’t like what I write,” he says.

Bamford is one of the foremost experts on the US’s electronic spying agency and its UK partner organisation, GCHQ in Cheltenham, Gloucester. His books and documentaries have shed often uncomfortable light on an increasingly powerful organisation with an estimated annual budget of over $10bn and some 40,000 employees. Despite its vast size, the organisation is so secret that even US senators were unaware of its existence. Its employees still speak of it as No Such Agency.

Bamford’s first brush with the NSA came during the Vietnam war, when he was posted in the Navy in Hawaii. There, his job was to plough through piles of top secret NSA reports and make sure they were delivered to the right people.

During law school, and running low on funds, he joined the Navy Reserves and secured a two-week posting in 1974 to one of the NSA’s key listening posts – Sabana Seca, Puerto Rico. Bamford says his main aim was to avoid doing any work during the school break.

But one day an intercept operator invited him to put on the headphones. He heard American voices – intercepted, he later realised, without judicial warrants. It was this discovery that propelled him to blow the whistle to a senate investigation and abandon a career in law to become an investigative journalist and author.

The beginnings of the NSA

The NSA was set up by president Truman in 1951 and formally established a year later, under a secret law that was kept hidden from the public and Congress. It had one aim initially, says Bamford, and that was to monitor the growing threat from the Soviet Union.

“The whole idea was never to allow another Pearl Harbor; to get an early warning if the Russians were about to launch a nuclear missile. So you’re listening to their air communications, their naval communications, all their communications, to develop intelligence,” he says.

However, the secrecy surrounding the NSA gave it substantial freedom – and potential for abuse. One of its founding principles was that the organisation does not have to follow government edicts unless they specifically mention the NSA.

About James Bamford

James Bamford is an author, journalist and documentary maker.

His books include: The Shadow Factory, Body of Secrets, A Pretext for War and The Puzzle Palace.

He writes for Rolling Stone, Wired and The New York Times.

“So if a president came out and said, ‘I am ordering all the federal government agencies not to do domestic eavesdropping,’ that is a get-out-of-jail-free card because, if he did not mention the NSA, the NSA did not have to follow that,” Bamford explained at a conference in 2014.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1990s, the agency was temporarily thrown into a crisis of identity. Its budget and workforce were cut dramatically. But the 9/11 attacks gave it a new lease of life – preventing terrorism – and the US government began pouring billions into the organisation.

Truck loads of money

“The NSA was given enormous amounts of money. It was just like dump trucks dumping money. Before 9/11, there really wasn’t much in the way of outsourcing, everything was done in-house,” he says. “They were given money that they could handle in the agency itself.”

For the first time, the agency began to outsource significant parts of its work to external contractors. Companies such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, SAIC and Booz Allen Hamilton secured lucrative contracts. That gave a vast army of security-vetted contractors access to the NSA’s secure networks and secret files – opening security risks for the organisation; Booz Allen Hamilton was later to employ Edward Snowden.

The expansion also created internal tensions. The NSA started investing hundreds of millions in developing a sophisticated surveillance programme, called Thinthread. That project was carefully designed to limit surveillance and meet the requirements of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (Fisa) and the Fourth Amendment of the US constitution.

But Bill Binney, former technical director at the NSA’s Signals Intelligence Automation Research Centre (Sarc) turned whistleblower, later revealed that those safeguards were jettisoned as the NSA poured billions of dollars into projects undertaken by external contractors that either failed or swept away the protocols built into Thinthread. The ethos appeared to move away from targeted surveillance towards gathering as much data on as many people as possible.

NSA city

Today the NSA is a vast organisation. Its headquarters in Fort Mead, Maryland, is, as Bamford describes it, like a small city, inhabited by tens of thousands of people with its own post office, fire department and police office. Hidden from view by forests, it is heavily protected by electric fences, anti-tank barriers, motion sensors and cameras. The buildings and windows are protected with copper shielding to prevent electromagnetic signals escaping.

Nearby – and nearly as well-protected – is the National Business Park, a hidden compound for the NSA’s high-tech contractors, Bamford reveals in his book, The Shadow Factory. The contractors include Booz Allen Hamilton, which occupies what Bamford describes as a 250,000ft2 “mausoleum”.

And in Bluffdale, the NSA has built its Utah Data Centre – known as the Bumblehive. The mammoth “mission data repository” cost at least $1.5bn and was designed specifically to store digital data gleaned from the internet. Bamford suggests it will be able to process all forms of communications, including the contents of private emails, mobile phone calls and personal data trails – including parking receipts and purchases at book stores.

The building will occupy over one million square feet, including 100,000ft2 of datacentre space. Forbes magazine estimates its capacity as at least 12 exabytes of data, and calculates that just 200 of its 10,000 racks of servers would be enough to store all the phone calls made in the US in a year.

Meeting Edward Snowden

The vast scale of the NSA’s interception programme became clear when Edward Snowden, a former CIA employee – then working for the NSA contractor Booz Allen Hamilton, – flew from an NSA facility in Hawaii to Hong Kong in May 2013. A few weeks later, under conditions of secrecy, he handed tens of thousands of classified documents over to journalists Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras and Ewen MacAskill.

Bamford is one of a handful of journalists to meet Edward Snowden in person. He spent three days with him in Moscow in 2014, interviewing and filming. Bamford already knew a lot about Snowden, having spoken to Glenn Greenwald and others, and through his own research. Nevertheless, he says, what most struck him was Snowden’s life story. “I didn’t know anything about him growing up, like when he was a kid,” he says.

Snowden’s family were models of respectability. His father spent his career in the military, his mother worked for the US court system, and his sister was a lawyer – not the sort of background you might expect of one of America’s most wanted fugitives.

As Snowden grew up, he spent time at his grandmother’s house and became fascinated with books about mythology.

“That sort of gave him these ideas of the good and the bad, you know, how somebody can fight against evil, fight against bad. That was all brand new to me, and that was really an interesting insight,” says Bamford.

Edward Snowden

Edward Snowden

At school, Snowden was forced to take time out for 10 months, due to illness. He missed his class year, and went to community college instead, where he developed a passionate interest in computers. “He’s like a natural born computer geek.”

Snowden wanted to follow his father’s footsteps into the military and serve his country. He aimed high, signing up for the US special forces.

“He wanted to not only join the army as an enlisted guy, but join the special forces. And, you know, he’s a slight guy. He’s smaller than me, very thin. So he’s not the kind of guy that is going in there because he’s macho,” says Bamford.

Snowden told Bamford that he was forced to leave when he broke both his legs during a training accident, and was discharged. He still wanted to serve his country, and ended up taking a job as a security guard at an NSA facility, gaining top secret security clearance along the way.

Snowden’s interest in computers and top security clearance ultimately helped him land a job in the CIA, then later Booz Allen Hamilton.

“It was there that he started seeing the video of the drones, and started meeting other people in the CIA who knew about the torture and all the bad stuff that was going on,” he says. “He started to see the darker side of what was going on, both in the military and the intelligence community.”

Collaboration between the US and Israel

One of the things Snowden was most outraged about, during his meeting with Bamford, concerned co-operation between the US and Israel.

Snowden disclosed that the NSA was passing the unredacted interceptions of the communications of Arab and Palestinian Americans to the Israeli government.

Normally, when the NSA shares such sensitive information, it removes personally identifiable information – but in this case, the NSA did not appear to be following its own rules.

“The Israelis could take that and blackmail Palestinians into going to work for them as spies, or use it to put them in jail. This is the United States giving information to another country that there’s no justification for,” says Bamford.

Bamford discovered that 43 members of a secret Israeli military organisation – known as Unit 8200 – had written to prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and to the head of the Israeli army, alerting them that Israel had wrongly used the information against innocent Palestinians for political persecution.

He wrote a critical op-ed piece about the affair for The New York Times, highlighting abuses.

“You’d think there would be a big outcry, but there wasn’t. There wasn’t any outcry at all,” says Bamford. “The public wasn’t outraged, congress wasn’t outraged. That’s the problem in doing this kind of work.”

Ultimately, it was discoveries like this that led Snowden on the path to becoming the world’s most notorious whistleblower. Remarkably, he was able to download hundreds of thousands of pages of NSA documents, and take them out of his offices, undetected.

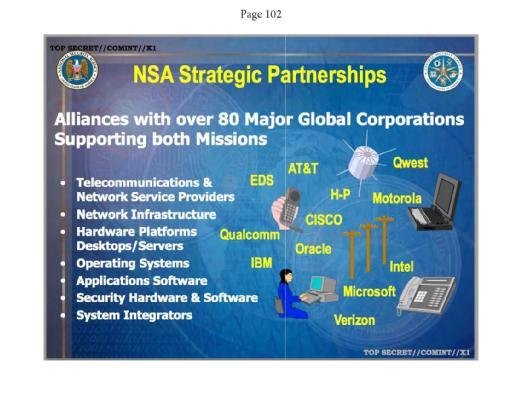

The documents Snowden handed over to journalists showed just how closely the tentacles of the NSA are entwined with US technology and communications companies. The agency relies on them – wittingly or unwittingly – to supply the electronic intelligence it gathers.

According to Bamford, it began with “Operation Shamrock”, in the 1940s and 1950s, when the US government put pressure on communications companies such as ITT, Western Union and RCA, to hand over telegrams without the judicial oversight required by law. “They used a lot of intimidation to do that,” he says.

“They set up this secret little office in New York, masquerading as a television tape company,” said Bamford, speaking at the Logan Symposium in London in 2014. Technicians collected tapes after midnight, copied them and returned them before the morning shift arrived.

Under Nixon, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the NSA expanded its operations, by supplying intelligence on US citizens involved in protests against the government. They included well-known figures such as actress Jane Fonda, singer Joan Baez and the clinician Benjamin Spock.

The NSA in numbers

5 countries; 50 partner countries 90 commercial partners; 20 major cable accesses; 20 covert cable accesses; 100 embassy interception sites; millions of computers affected by NSA malware.

Source: Duncan Campbell, investigative journalist, speaking at the Logan Symposium 2014.

Telephone calls, telegrams and telexes from thousands of innocent people were vacuumed up by the NSA, which had a policy of collecting everything, even tangentially related to their investigation, Bamford revealed in The Puzzle Palace, the first book to lift the lid on the NSA.

In the 1990s, the NSA proposed that US telecommunications companies adopt the Clipper Chip to encrypt communications. The chip contained a backdoor that would allow the NSA access – it attracted opposition from the public and telecommunications companies themselves.

It was eventually dropped but, behind the scenes, the NSA was making other secret arrangements with telecommunications and IT companies.

The reach of the NSA’s tentacles became exposed to public scrutiny when the Guardian, the Washington Post, Der Speigel and The New York Times published their analysis of the Snowden documents.

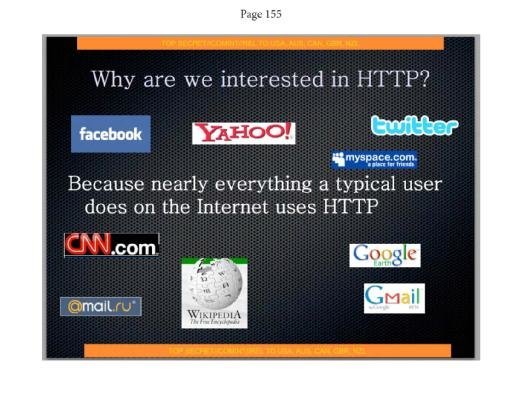

Prism, a programme which allowed judges to order the disclosure of data about customers from Microsoft (including Hotmail) Google, Facebook, Yahoo, YouTube, Paltalk, AOL and Skype, is perhaps the best-known example.

Another programme, Operation Muscular, sought to bypass the encryption Google and Yahoo use to make their customers’ emails private, allowing the NSA to hoover up data on a much larger scale.

“The fibre optic links between the companies and their datacentres, or between the datacentres themselves, were unencrypted, so they were able to access that,” says Bamford. An NSA PowerPoint of the operation shows a smiley face where the encryption is removed.

Meanwhile, the NSA’s Tailored Access Operations (TAO) unit intercepted Cisco servers, routers and network gear in transit, and installed covert interception devices before they were repacked and delivered. The operation gave the NSA backdoor access into networks around the world.

The collateral damage to technology firms

The disclosures damaged confidence in the technology companies, from both businesses and the public – and damaged them financially.

“The last figures I saw, it was costing them a huge amount of money in lost sales,” says Bamford. “Because if somebody’s going to spend a lot of money, millions of dollars, on a system, why would they buy it from a company where they know there’s a backdoor to NSA? So they’ll go to a Swiss company, or a French company or they’ll go someplace else.”

Brazil, for example is looking to build an undersea communications cable to Europe to bypass the US, and switched from buying satellites from a US company to a French company, says Bamford.

Firms such as Apple and Yahoo are now encrypting their systems so the government does not automatically have access to their customers’ metadata.

And some US cloud-based companies are starting to offer services guaranteeing customers that their data, and support and maintenance services, will be kept in Europe.

“I think they realised that that’s the only way they’re going to start getting some of their customers back,” says Bamford. “There are a lot of people losing a lot of money in Silicon Valley because of this.”

GCHQ warns technology companies

But there is little sympathy from government for the technology companies.

Robert Hannigan, then director of GCHQ, fired a shot across the bows of US internet companies in 2014, warning them not to go too far to protect their customers’ data, in the face of terrorist threats such as Daesh.

Like it or not, he argued – in remarkably strong terms in a newspaper article – US technology companies have “become the command and control networks of choice for terrorists and criminals”.

Bamford sees Hannigan’s comments as public support for the NSA’s lobbying to expand its data-gathering capabilities.

“I think that he was basically supporting the NSA’s position, which is that the NSA and GCHQ should be able to get access to that information whenever they want,” says Bamford.

It is perhaps not surprising that Hannigan should have spoken out so strongly, given the close working relationship between the two organisations. They are part of the Five Eyes network, a group that shares electronic intelligence with the US, UK, Australia and New Zealand.

The NSA’s twin brother

The relationship between the NSA and GCHQ is far closer than the relationship between the NSA and the CIA, says Bamford. “The NSA and GCHQ are like twin brothers.”

And for good reason. GCHQ has access to all the satellites across Europe and the transatlantic cables which are a rich source of intelligence for the NSA.

When workers at GCHQ’s Cheltenham headquarters went on strike for a week, the NSA took up the slack. And when the NSA’s director, Michael Hayden, received a phone call alerting him that all the NSA’s computers had crashed in 2000, GCHQ stepped in to cover.

“General Michael Hayden was at home, around seven o’clock on a Sunday night, and the guy in charge of the operation centre called up and said, ‘All the computers have crashed.’ And Hayden said something like, ‘which one?’ He said, ‘All of them.’ And then they kept it a secret for about a week. That was a big deal,” says Bamford.

Pat and Louis – the antennas

Bamford has uncovered close financial links between the two organisations. In the early 1980s, for example, he obtained documents which showed the NSA had paid for two large antennas at GCHQ’s intelligence-gathering facility near Bude in Cornwall.

The then director of GCHQ was so grateful that he wrote to his counterpart at the NSA, Pat Carter, saying the dishes should be named “Pat”, after him, and “Louis”, after his deputy director, Louis Tordella.

“They talked about how ‘our employees are in bed with each other’ and ‘should we pull the sheets up tight’. But that’s the way it’s been – GCHQ people at NSA, and NSA out here in the UK,” he says.

The relationship between GCHQ, the NSA and the other Five Eyes partners is a complex one.

Bamford had sight of one document in the Snowden archive that showed that US policy is to honour its agreements with its collaborators only if it is convenient to do so.

“It was fascinating, because it stated in black and white that the US would honour its agreements with its partners – unless there is a reason not to,” says Bamford.

“So it made no sense. If one side can unilaterally go against the nature of the agreement, then there really isn’t an agreement, right?”

US citizens protected by law

While in theory there are laws to protect US citizens from being monitored by the NSA, there are few similar protections for UK, or other non-US, citizens.

“There is nothing at all legally, or any other way, preventing the NSA from eavesdropping on non-US citizens,” says Bamford.

If anything, GCHQ has fewer legal constraints than its larger counterpart, he says. “There are things that GCHQ does that I don’t think the NSA could get away with.”

German news magazine Der Speigel, for example, exposed a “dirty tricks” unit in GCHQ, dubbed My Networks Operations Centre (MYNOC). One of its tasks was to create fake LinkedIn pages, infected with malware. It used them to target engineers working at the Belgian mobile phone company, Belgacom, opening up a gateway into the phone company’s networks, and its customers’ mobile phones for an extensive surveillance operation.

“That’s an area that I think would be a little beyond the pale for NSA. But for GCHQ and this organisation MYNOC, there’s almost no limit to what they do,” he says.

More recently, GCHQ has admitted in court that it carries out Computer Network Exploitation (CNE) – in other words hacking – in the UK and overseas.

The agency has the ability to turn on microphones and cameras on electronic devices without the owner’s knowledge, identify a person’s location and to make copies of personal documents.

The projects have fanciful names, such as Nosey Smurf, which plants malware to turn on smartphone microphones; Dreamy Smurf, for switching on smartphones; and Paranoid Smurf, for hiding malware on mobile devices.

GCHQ told the court that the measures are proportionate, and conducted under strict legal safeguards. Opponents argue that the warrants are so broad they could allow GCHQ to legally hack all the phones in a city.

Fighting terrorism – missed opportunities

The NSA has grown enormously over the past decade, in its capability, financial resources and political power. And in the 1990s, the NSA stepped up its fight against terrorism.

“They were terrible at it,” says Bamford. “I mean, the first World Trade Center attack in the early 1990s, they completely missed, even though there was a lot of planning back and forth between the Middle East and the conspirators in New York. And they missed the attack on the USS Cole in Yemen. Yemen was a big target. And they missed the attacks on the embassies in East Africa. These are really big deals. Two US embassies blew up, they didn’t have a clue.”

The 11 September 2001 attacks against the World Trade Center caught the NSA off-guard. “General Hayden [the NSA director] watched it happen on his television in his office, no clue whatsoever,” says Bamford.

Bamford lists a long list of other cases the NSA should have known about: The underwear bomber, the attempted bombing in Times Square and the Boston Marathon bombing. “Even though they’d been communicating back and forth to Chechnya, and flown back and forth, they had no clue,” he says.

After the Snowden revelations, the NSA said publicly that it had found more than 50 incidents where it was able to find clues to terrorist plots. But even that didn’t stand up, claims Bamford.

“After they were questioned by the Senate Intelligence Committee, it got down to one. And that one was a taxi driver in San Diego who sent $8,000 to some group in Somalia,” he says.

Calls for checks and balances

Following Snowden’s leaks, there has been widespread pressure to introduce checks and balances to control the workings of the NSA and GCHQ.

US technology companies are among those pressing for the US government to restrain the NSA, and bring it under greater legal control. In the UK, internet service providers (ISPs) have brought challenges in the interception of communications tribunal.

There have been some changes. The NSA has lost its legal authority to collect bulk records of phone metadata on American citizens, following the passage of the US Freedom Act. The executive branch will now have to apply to the US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to require telecommunications companies to hand over specific records. There is no such protection, however, for phone or internet traffic of non-US citizens.

But Bamford sees little sympathy for technology companies in Washington. It is simply not a vote winner.

After the Snowden revelations broke, the people who were fighting most against the NSA were the biggest losers in elections. There were only two senators fighting for reforms – Mark Udall and Ron Wyden – and Udall lost his seat.

“The critics are getting fired and the people pushing for more and more spying have basically been winning,” says Bamford.

If anything, Bamford says he has seen an appetite in the White House to ensure that technology companies co-operate more with the intelligence agencies.

“I’ve seen these proposed legislations to force these companies to give them the keys to the encryption,” he says.

In an address to the nation in December 2015, president Barak Obama hinted at plans to toughen the government’s stand against strong encryption, urging high-tech leaders to make it harder for terrorists to hide from injustice.

Hillary Clinton, the Democratic front-runner to succeed Obama in 2017, has joined the fray, saying technology companies need to join the fight against Islamic State.

The UK has seen the draft Investigatory Powers Bill, which sets out powers for the security and intelligence services to collect telephone and internet data from communications companies in bulk.

The bill will require ISPs to keep records of every website visited by the public for a year. There are powers for police and the security services to carry out hacking, and powers to demand access to encrypted communications from technology companies.

Where is the outrage?

Bamford is surprised just how little outrage there has been in the UK over the growing encroachment of the state on people’s private lives, without the strong oversight that should demand.

“You have somebody like Snowden who basically gives his life away, and then there’s only a temporary outrage and it goes away, and everything’s back to normal again,” he says.

The reaction has been stronger in Brazil, where president Dilma Rousseff cancelled a state visit to Washington, following allegations that the NSA was intercepting her emails and messages, along with those of the state oil company, Petrobras.

And in Germany, where the country’s relations with the US were shaken after it emerged that the NSA had eavesdropped on chancellor Angela Merkel’s mobile phone.

“I would think there’d be more outrage in what they’re doing domestically, but it’s far less than I would expect. And I think a lot of it is because of we have this post-9/11 attitude where, whatever the government is doing, it’s doing to protect us from the terrorists,” he says.

Still more to learn from Snowden

Bamford thinks there is still a huge amount to learn from the Snowden documents. US government estimates that the cache amounted to some 1.7 million documents, but Bamford believes 200,000 is nearer the mark.

“There’s a lot more there. And even the documents that have come out really haven’t been thoroughly analysed. One reason is because they’ve come out in so many different places, the Guardian, Der Spiegel, Dutch newspapers and Brazilian places. So, nobody’s really consolidated all that.”

After dedicating his life to researching the NSA, Bamford says his disclosures are dwarfed by the contents of the Snowden archive.

“I’ve written about the NSA for 30 years, and I couldn’t imagine most of the stuff that’s come out from Snowden,” he says.

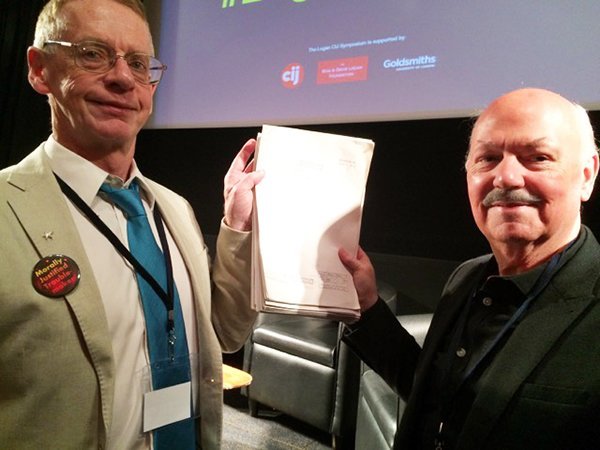

Bamford reunited with top secret document after 30 years

James Bamford risked prosecution as he researched his first book to expose the workings of the ultra-secret US National Security Agency, The Puzzle Palace.

The book had its genesis when Bamford, a serving member of the Navy who spent a holiday job working at an NSA outpost, felt outraged enough to blow the whistle about the agency to a Senate enquiry.

In 1975, the Church Committee had begun holding enquiries into the government targeting of anti-war protestors, including celebrities such as Jane Fonda and Benjamin Spock, by the intelligence services.

When the NSA told the committee that it stopped intercepting US citizens a year and a half earlier, Bamford knew from his own first-hand experience that officials were not telling the truth.

While studying for a law degree, he had spent a two-week placement at the NSA listening post of Sabana Seca, Puerto Rico, and heard for himself the sound of American voices through the headphones of one of the operators.

Bamford turns whistleblower

Bamford was allowed to testify secretly in senator Church’s private office. The committee took his testimony seriously enough to pay a surprise visit to Sabana Seca, and found – to the NSA’s embarrassment – that American citizens were indeed still being spied on.

As more revelations about the NSA emerged, Bamford put aside his law career and set out to research the first in-depth exposé of the NSA, The Puzzle Palace.

Remarkably, he was able to obtain thousands of pages of material on the NSA, using the US Freedom of Information Act, and from private library archives. He found he was able to walk into the NSA headquarters, sit in the lobby with a coffee and a paper, and listen to the conversations going on around him.

In a gripping account in The Intercept, he tells how he was working on his books with documents strewn across a table in a coffee shop, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when he picked up an alarming message on his answering machine.

It was from a senior attorney with the US Justice Department, asking him to call back extremely urgently. It did not take Bamford long to work out what the attorney wanted.

It was a copy of a 300-page criminal investigation by the Justice Department into the NSA. Bamford had obtained it quite legally under the Freedom of Information Act, and now the NSA wanted it back. The document was explosive, revealing criminal breaches at the heart of the organisation.

Bamford had already taken the precaution of making a second copy – an expensive undertaking for a struggling author, at 10c a sheet – and now he needed to get it out of the country quickly.

“I was very worried that they were going to, you know, break into my house and grab it,” he says.

He spoke to a friend and journalist at The Sunday Times in London, who told him that a colleague was flying from Boston to London that night, and could take the document with him.

“I was told he’d meet with me and take the document – but he didn’t want to know who I was or what was in the document, in case he got stopped. I met him on a street corner in Boston and he took it to London,” he says.

Threatened with prosecution

Back in the US, Bamford was threatened with prosecution under the espionage law of 1917 unless he returned the document. He was summoned to a meeting with his publisher, where NSA lawyers who had seen the document asked how many copies were in existence.

“They started threating the espionage statute, then they threatened me formally with prosecution under the espionage statute if I did not give it back,” he told the Logan Symposium in 2014.

“Well, I never gave it back, and they eventually went away. But that was when I first became familiar with the way the NSA can go after you if they really want you not to have something,” he said.

Working with a lawyer, he found a paragraph that said that, once a document had been de-classified, it cannot be re-classified.

“They said, well, forget about that, we are still going to prosecute you if you use it. Well, I did use it, and I didn’t get prosecuted. That is why I have a lot of respect for whistleblowers.”

The second document remained hidden behind a panel of a bath in Islington, London, for 18 months.

Bamford was eventually reunited with it during a conference in 2014, when it was returned by fellow investigative journalist and NSA specialist Duncan Campbell (pictured).

“That was one of the biggest surprises I’ve ever had,” says Bamford. “It brought me back to a whole different era. I mean, that was an era before there was the internet, before there were computers and I wrote The Puzzle Palace on a typewriter.”