grandeduc - stock.adobe.com

How crowd simulation modelling enables organisations to develop social distancing strategies

Crowd simulation modelling has a role to play in maximising the Covid security of offices and other buildings by facilitating social distancing to help get people back to workplaces

The Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic has created unique challenges, with remote working and social distancing measures being hastily introduced in March. However, certain sectors are keen for staff to return when possible, and are analysing crowd simulation models to develop more effective social distancing measures.

Since March 2020, many premises have been relatively empty, but the government is keen to revitalise the economy. Against a rapidly changing backdrop of rules and guidelines to curb the spread of Covid-19 is the need to ensure that public buildings and premises can either safely remain open or plan to reopen as safely as possible.

Rather than relying on a static two-dimensional image of a building layout, which can only show pinch points in terms of two dimensions and does not demonstrate how people will interact with the layout, crowd modelling more accurately reflects how people move within a building or public area.

“Every single organisation out there is working on a plan for social distancing measures,” says Shrikant Sharma, director of people movement and analytics at engineering consultancy Buro Happold. “The challenge is twofold. All those plans are dealing with the static aspect of social distancing. You can take the paper and put some dots on it, but there are so many unanswered questions there. We can map those in a static sense, but the real risk is when those dots move – that is hard to predict.”

Crowd modelling software has been used for 20 years to simulate the movement of groups of people. It can be broken down into three distinct methodologies:

- Flow-based approach – focusing on the crowd as a whole, these are mainly used to estimate the flow of movement of a large and dense crowd in a given environment.

- Entity-based approach – models implement predefined global laws that simulate social and psychological factors of a crowd. Used to research crowd dynamics.

- Agent-based approach – using autonomous individuals, each agent has a degree of intelligence, allowing them to react based on a set of decision rules.

Crowd modelling is mostly used in urban planning, for visualising how people will navigate buildings, and particularly for evacuation modelling, highlighting any possible pinch points. It has also been used by the retail sector to identify key areas where people will see products. More recently, it has been used by organisations and private companies to model social distancing measures within their premises.

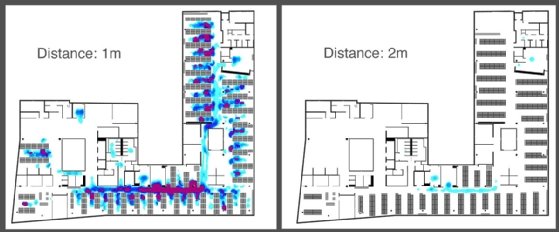

Crowd modelling software can use conflict analysis to determine whether people are likely to come into contact or close proximity with one another. Conflict analysis can be used to identify pinch points in a building. In this case, the conflict zone is set at the regional requirement for social distancing, such as two metres for the UK. The simulation then models the crowd’s movements and identifies all possible conflict zones.

The engineering consultancy Arup used MassMotion to model staff movements in its premises, as well as those of its clients, thereby allowing it to calculate how many staff it can safely have at each location.

Building a model

As with all such simulation modelling, the more complex a model, the longer it takes to build. However, the time invested in building the initial model and embedding all the necessary parameters saves time in the future.

“We then add a series of simulation parameters, such as going to the toilet,” says James Ward, associate director of architecture at Arup. “These are easier when they’re predictable. An office floorplate is a fairly predictable environment, but a lab or manufacturing facility requires a more detailed conversation to understand exactly how they use that space.”

At the very least, a 2D plan of the layout of the premises is required, the more detailed the better. This plan is adapted, using a computer-aided design (CAD) package, and then inserted into the crowd modelling analysis tool. At this point, different areas can be designated, such as printers and coffee machines (where people naturally congregate), as well as meeting rooms and reception areas.

However, acquiring sufficiently detailed layouts can be challenging, as organisations rarely have such plans readily available. Instead, these are often with third-party contractors, hence it can take time to acquire the information.

Measuring movements

The next stage is establishing the dynamics of the people in the premises. This is not just the number, but also their entrance and exit patterns, and the composition of people, in terms of age and role within the organisation.

“How a child might interact with a building will be very different to a businessman who is used to going in and out of the building all the time,” says Neil Manthorpe, associate director of landscape architecture and urban design at Atkins. “Another group that’s often referred to is the elderly, who need more time when they’re crossing a road or entering a building.”

Estimating the potential number of people within a private building, such as an office, can be quite simple, as is understanding the expected composition, because organisations will already have this information through their employee details. In a public space, the number and composition of people can be estimated, based on the environmental factors, but for more accurate results, direct observation of people within the area may be the best solution.

Gaining an understanding of entrance patterns can be difficult. In a private building, this information can be obtained by acquiring permission to record phone signal data, thereby detecting the movement patterns of people (or, at least, their phones) entering the premises.

In a public space, permission to gain people movement information can be more challenging. Traditionally, turnstiles have been used to record the numbers and patterns of people entering and leaving an area. However, due to Covid-19, this is not so viable, due to people having to touch the turnstile.

This information could be obtained by visually observing and recording the movement of people, either directly or remotely. Due to data protection, using technological solutions to process data related to movements of individuals in a public space can be challenging.

Running a simulation

With all the necessary environmental and people movement information gained, a crowd can be simulated and analysed. The time it takes to run a simulation varies, but the simpler the model and the more powerful a machine, the shorter the time will be. “It depends on the number of agents and the amount of time that you want to simulate,” says Ward. “If we were to give an example, a seven-and-a-half-hour simulation with 200 people is five minutes.”

These simulated results are presented as a series of heatmaps, identifying potential areas where people will come into close proximity with each other, where the “hotter” the area the greater the number of such incidences. These gradations of conflicts allow organisations to focus on preventing or mitigating contact in the key areas of their premises.

One of the greatest strengths of any simulation is being able to change the parameters and see what the consequences could be. This makes crowd modelling ideal for organisations developing optimum social distancing strategies, as multiple social distancing policies can be simulated in a short amount of time, without putting anybody in undue danger.

Analysing the simulations allows organisations to identify pinch points. In turn, this allows organisations to experiment with the model. For example, they may consider moving desks to change the office layout, or introducing measures such as staggered meeting times, adopting a one-way system through the building and staggering employee start and finish times.

Furthermore, presenting these findings to staff demonstrates that due diligence has been performed, restoring confidence and staff morale that all considerations have been reviewed in adapting the workplace to prevent contact.

Holistic approach

Nonetheless, there can be a danger in organisations believing that simply conducting crowd simulation modelling will suffice. “The important limitation is it’s obviously a geometric tool and we’re not health experts,” says Ward. “These tools help people understand whether the physical planning of their space facilitates people to socially distance the majority of the time, minimising the risk.”

This information should be combined with advice from healthcare experts to provide a holistic approach. This allows organisations to create the safest possible environment for employees and the public.

Research into crowd modelling is ongoing. Researchers at Trinity College Dublin recently used a crowd simulation tool, designed for the entertainment industry, to mimic the effects of social distancing in a crowd. The Smart Assets for re-Use in Creative Environments (SAUCE) tool treated each person as a walking magnet, where every other person in the scene repels depending on the strength of the magnet.

“We simply calibrated the system so that at a two-metre distance the level of repulsion was high, giving a social distancing effect while navigating,” says David Smyth a research assistant in computer science at Trinity College Dublin.

By this time next year, subject to a vaccine being available, the Covid-19 pandemic may be a painful memory. But until then, organisations need to undertake due diligence in protecting their staff and members of the public. Using crowd simulation modelling allows organisations to optimise social distancing policies, maximising the safe capacity of the premises without unduly endangering their staff, contractors or members of the public.

Read more about data modelling to combat Covid-19

- Coronavirus: Mobilising data science.

- Modelling the world of Covid-19.

- Cleveland Clinic’s Covid-19 strategy driven by data modelling.