Councils explore options for online mapping tools

Councils are drawing on Ordnance Survey, Google Maps and OpenStreet Map for online mapping. What’s the optimal mix?

All parts of the public sector in Great Britain have free access to a wide range of services from the government-owned mapping agency Ordnance Survey (OS), through the Public Sector Mapping Agreement in England and Wales or the One Scotland Mapping Agreement. Every local authority makes some use of the data available through OS.

However, a number of councils are choosing alternative options for online mapping. Several use Google Maps, which has charged high-volume users since 2012, but remains free for most. Others have adopted the wiki-mapping service OpenStreetMap (OSM), which was set up in the UK in 2004.

Meanwhile, OS has been expanding its range of online services and interfaces, including open data. The result is a range of choices for online mapping, including options requiring virtually no technical knowledge to generate and others allowing extensive customisation.

Ordnance Survey wins on accuracy, with a government mandate to include new developments and the best coverage of the countryside, but it has sometimes been slower to offer the latest services.

OpenStreetMap is considered better than Google and – in some cases – OS on a few features. Councils can add to OSM if they wish, but as a user-generated service its quality varies. Google Maps is strong on roads, can be shared easily and is familiar to the public, but it is weak on other geographical features.

Plymouth City Council

Plymouth City Council chose Google Maps to present data on roadworks and traffic, as well as the locations of sports pitches and car parks.

“Whether we love or hate Google, it’s a product people use,” says corporate web manager David Hodder.

“From our point of view, there’s almost zero maintenance after it’s created,” he says, adding that, over five years, the city has never come close to the page view limit at which Google starts charging.

Plymouth has an in-house geographical information system (GIS) from GPC, which uses Ordnance Survey mapping, with the planning department its biggest user. The city uses static extracts from this system for online planning applications, but is not able to generate live online maps.

“We had to find a plan B. We looked at Bing Maps and some Ordnance Survey maps and they’ve all got their pluses and downsides,” said Hodder.

The city is currently tendering for a revamp of its website, but expects to stick with Google Maps.

Plymouth’s outsourced highways manager Amey provides the map of roadworks and traffic on the city’s website. This also provides email updates to subscribers, with users including the local media.

“It’s the best example of online mapping we have at the moment,” says Hodder.

“It’s basically Amey’s back-end management system – it exposes part of that and it feeds the Google map. That’s how we’d like the rest of the site to work – we update back-office systems and it populates a map,” he says.

Oxford, Google Maps

According to Hodder, online mapping services are accurate enough for many purposes, but not all.

“We look at maps in two different ways. There are parks, car parks, nature reserves and so on where it doesn’t matter if the pin is five metres to the north,” says Hodder.

“Then you’ve got the operational side of things like planning, where you need to be perfect. We wouldn’t use Google Maps for the operational maps,” he says.

The city has produced a prototype map with OpenStreetMap to display tree preservation orders, uploading an Excel spreadsheet with locations and data.

“It’s currently a proof of concept, to see how easy it is to use and if it can do all the things we want it to do,” says Hodder.

“Like Google Maps, it doesn’t link to any back-office systems. We would still have two different data sets in different places, [but] it’s very simple to use, very quick to use and definitely an option for the future.”

Surrey Heath Borough Council

Surrey Heath Borough Council, which shares service provision in its area with Surrey County Council, was an early adopter of OSM. “When we started we had the M3 motorway running through the borough and that was it,” says GIS manager James Rutter.

Surrey Heath added the rest of the area’s roads to the system, as well as individual buildings in towns. Rutter also formed a syndicate with the other Surrey districts to buy the data rights to an aerial survey produced by a company that had gone into liquidation and gave it to the OSM community.

Rutter says many councils are locked into proprietary systems for their websites, but Surrey Heath has made a shift to open-source platforms, including the Postgres database, Mapserver and OpenLayers to generate maps.

“With online mapping, we’re also going down the road of consuming services already out there, instead of reinventing the wheel,” he says.

With a new website just launched, based on the open-source Drupal content management system, the council plans to use cloud-based web mapping service CartoDB with Safe Software’s FME data conversion software.

“There are still people happy to sit behind their £20,000 GIS installation and get it to do everything,” Rutter says. “Local authorities shouldn’t be paying to build their own infrastructure when there’s infrastructure out in the cloud we can use for not much money.”

One problem with using web services is the security policy of the Public Services Network, which militates against their use. As a result, Surrey Heath runs some services internally.

The council is developing the new site with maps from Here (which was recently sold by Nokia to car-makers Audi, BMW and Daimler for €2.8bn), but is looking at using Mapbox’s tiling service to move to OpenStreetMap, with another of Surrey’s district councils considering the same system.

“It’s a quick response map. We can put what we like on the map, rather than what Ordnance Survey wants to put on the map,” says Rutter. “We’re trying to balance whether we want to display OS MasterMap data on a website – I’m not sure we do.”

Oxford, OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap is produced to a “best endeavours” standard, which makes it unsuitable for uses that require complete accuracy, such as details of planning applications. But Surrey Heath and others in the county use OSM for a navigation map that helps users find planning applications of interest, through the Surrey Planning Hub.

Although OSM is run by volunteers, it is keen to encourage corporate use of its mapping and provides information on switching. Harry Wood, a volunteer for the OpenStreetMap Foundation, says it has details other maps lack. “Parks are really well mapped, as people get excited about them,” he says, while the OpenCycleMap.org project provides cycle routes and parking.

Google and OS provide users with “tiles” – squares of map image – from their own servers. OpenStreetMap asks users to download the tiles and data they want and put them on their own servers – OpenLayers and Leaflet are JavaScript libraries that can be used for this – or use a third-party provider such as MapQuest Open.

A straightforward image of a map with an option pin can be downloaded in several formats directly by using the OpenStreetMap.org site’s share function.

According to Wood, Google – which did not provide a spokesperson for this article – can claim ownership of whatever users add to its maps and is only licensed for use on freely available websites rather than intranets. As OSM uses a Creative Commons licence, it imposes no such restrictions.

“OpenStreetMap was born in the UK out of frustration with Ordnance Survey, but we’re working much more closely with them,” says Wood.

OS’s Geovation Hub hosted OSM’s London Hack Weekend on 8-9 August 2015. OSM has made some use of open OS data, although he says this is used more often for checking rather than as a primary source and OSM does sometimes spot OS mistakes.

While welcoming OS’s development of open services, saying he believes “OSM helped bring that to market”, Wood says these aim to entice people into paid-for ones. Overall, he encourages web developers to judge things on their merits, even mixing and matching by overlaying OSM’s cycle route data on OS mapping.

Oxford, OS Map Builder

Ordnance Survey has grown more comfortable with OSM too.

“There’s absolutely a place for OpenStreetMap – it blows my mind that there are so many people contributing,” says Nick Turner, head of application programming interfaces (APIs) and platforms at Ordance survey.

“But the differences between OSM, Google and OS are very clear. We have a mandate from government to map all new developments across Great Britain. The consistency of our mapping works across the country – the same can’t be said of crowdsourcing or our competitors,” he says.

The state-owned mapper was initially hostile to open data, but has gradually embraced it, with OS OpenSpace API appearing eight years ago.

“You need to have some nuance as a developer to use it, although we provide some tools,” says Ian Holt, product manager for mapping APIs at OS.

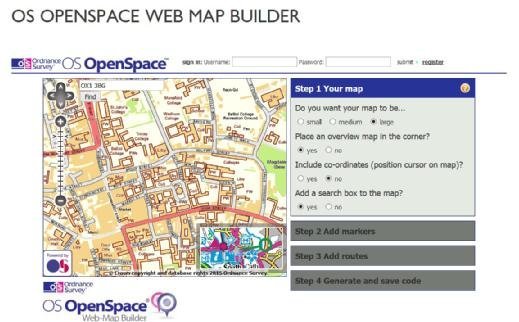

The simplest tool to use is the web map builder, which allows users to add pointers and routes to maps through a graphical interface that then generates HTML.

OS also provides open data. In March 2015, it added four new services: OS Open Map, a customisable base map; OS Open Names, a location search covering 2.5 million locations and has a free API; and open data on Great Britain’s river and road networks. The first month of availability saw 50,000 downloads.

Norwich City Council

Turner says that around 50% of local authorities use OS maps on their websites, but he believes there is room for growth. Councils can use their free access to OS data to build their own mapping services, he says, but can also use partner organisations.

One council that took the latter option is Norwich City Council. Its MyNorwich service, which lets users enter addresses and postcodes to find out about local council services, was developed by Local Government Shared Services using ESRI software, using OS’s VectorMap Local and MasterMap Topography Layer. The city believes it has already saved £15,000 by shifting queries previously made by phone and in person to the web.

Anton Bull, Norwich’s executive head of business relationship management and democracy, says quality and accuracy were the main reasons for choosing OS.

“Being a city authority, what’s happening on the ground changes on a regular basis and it is essential map and address updates are captured as quickly as possible to make sure all households are included,” says Bull.

He added that, while other options were considered, OS MasterMap provided the detail and rapid updating Norwich required. The city has also hosted the region’s meetings between OS staff and liaison officers.

“Having a one-to-one contact with an area representative is a great asset, which has made problem solving and feedback a smooth and effective procedure,” says Bull.

Read more about online mapping

- Ordnance Survey is embarking on a project to foster startups, applying its vast repository of data to solving emerging challenges around urban spaces and smart cities

- Ordnance Survey pulls 17 databases into one Oracle geospatial database management platform.

- Harnessing the power of big data presents insurers with a business opportunity, but is the industry ready for it? Ordnance Survey’s Sarah Adams believes they are.