A guide to smart home automation

Unless it is a new build, the challenge in creating a smart home is that technology must work irrespective of the age of the property

Unless it is a new build, the challenge in creating a smart home is that the technology must work irrespective of the age of the property.

While it is far from mainstream, more and more smart home technology is starting to appear in the market. Energy supplier Npower recently started offering Nest, the smart central heating controller from Google in the UK, and last year, rival British Gas launched its internet-connected central heating system, Hive.

But beyond the big energy providers, a new industry is emerging to integrate computer control into the home. In the past, companies such as Lutron were synonymous with intelligent lighting installed in high-end homes.

Like the trend in IT consumerisation, smart home technology is becoming more accessible. For instance, electronics and white goods manufacturer Philips' Hue family provides a Wi-Fi-enabled light that fits into a standard light socket and can be made to dim and change colour using a smartphone app.

Other companies, such as D-Link, are focusing on remote home security, such as its Wi-Fi-connected CCTV cameras. Motorised curtains and shutters can be controlled remotely via RS434 control boxes. Meanwhile, smart TV and stereo equipment manufacturers such as Sonus offer devices compatible with the Digital Living Network Alliance (DNLA) specification, which means they play media and can be controlled via a local area network.

What many of the newer smart home products have in common is that they are underpinned by internet connectivity and cloud services, and, collectively, they are part of what the IT industry calls the internet of things (IoT). These products offer some degree of intelligence – either built-in or via the cloud – and they may contain a sensor, such as in internet-connected CCTV cameras, fire alarms and thermostats.

Requirements for a smart home

- Every device is connected

- Every device has some level of intelligence

- The house is connected to the cloud

- Ability to split the application from the function of the device, for example a Sonus stereo could be used to broadcast an alert

- Customer can add new apps or services

Source: Martin Vesper, CEPO, digitalSTROM

Long-life devices

Unlike a smartphone, central heating systems and white goods such as fridges and washing machines generally last a fair number of years. Although some newer domestic appliances may have smart technology built in, consumers should not have to upgrade to take advantage of what a smart home can potentially offer.

But these timescales are not compatible with the six to 18-month schedules that seem to drive consumer electronics.

Past experience has shown that the computer industry does not have the appetite or the patience to support products that may be around for decade.

Last year, British Gas’s Connected Homes business ran a competition in which startups were invited to showcase smart energy technology for the home. Although there were plenty of innovative product demonstrations, a responsible home owner might question whether the technology being embedded in the home, and the companies that provide it, will last as long as the bricks and mortar.

Smart home in practice

Computer Weekly recently visited the home of Martin Vesper, CEO of digitalSTROM, a German company that has developed technology to connect up the wiring in a home to make it a smart home.

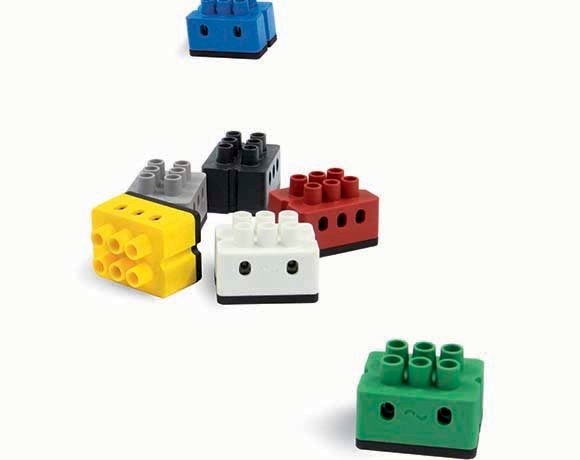

A computer built into an electrical block is used to add intelligence to devices connected to mains electricity. The terminal block is similar to the one an electrician would use to connect a light switch to the main lighting circuit, but the presence of a computer means the switch has intelligence.

According to Vesper, the technology has been engineered in such a way that a light switch can not only be dimmed and can measure electricity consumption, it can also collect data via the on-board computer.

The device communicates, using powerline Ethernet, to a mainboard located next to the house's fusebox, which avoids the need for Wi-Fi connectivity. Vesper says: “We are able to take an existing home, which may be 20 or 30 years old, and make it smart.”

Once the electrical appliances or light switches are connected to the intelligent terminal blocks, and networked over the mains, each can then be identified on the network and controlled independently. This makes the system flexible compared with the fixed wiring in a house.

“In a standard home with fixed wiring, if you want to change something, you need to make the change to the hardware,” says Vesper. “But the digitalSTROM system is software-driven. I can change how the light operates via a tablet or PC, and suddenly it will be configured to do something different.”

More articles on the internet of things

- Video interview with Martin Vesper, CEO, digitalSTROM, on smart home technology

- Business value from the internet of things

- Gaining competitive advantage in business through the internet of things

Software controlled

In Vesper's vision, a smart home should be configurable using software, which makes it flexible. It should also be possible to combine events such as a light switch being toggled to orchestrate several activities.

For instance, a single switch on the digitalSTROM system, which controls the dining room, can be reconfigured to switch on other lights, such as the hallway or kitchen. “You can also do new things and combine events such as a doorbell and a hi-fi system,” he said. Such a setup could be used to announce that someone is at the door.

The digitalSTROM system uses a central control console and Linux server, fitted in the home’s fuse box, which provides a way to share data between other intelligent terminal blocks to co-ordinate activities and monitor events, such as when a smoke detector has been tripped.

The system uses orchestration software from Tibco to link events together. This enables a light switch, a door bell or an alarm, such as a smoke detector, to fire off a number of events. Because the action of the switch (or alarm) is separate from the trigger event (such as pressing the door bell), it is possible to reconfigure its behaviour. During the demonstration, Vesper showed how his dining room switch could be reconfigured to switch on the lights in the kitchen as well as those in the dining room.

The idea of consumer-configurable services for smart homes is one of the uses for a technology called IFTTT (if this happens, then do that). The idea is that the user can trigger an action based on an event.

As consumers add individual smart products, they will realise new tasks that this combination of gadgets could addressFrank Gillett, Forrester

A new iPhone app called Manything is using IFTTT to turn an old iPhone into a CCTV monitoring system. For a monthly fee of £4.99, two old iPhones can be set up to act as motion sensors and record video if motion is detected.

In a blog post commenting on Manything, Ovum analyst Michael Philpott noted: “Home monitoring and security products can cost hundreds of dollars to set up, and then work only with proprietary software, restricting the user in terms of hardware choice and overall functionality.

“Manything’s solution of using existing technology that consumers may already have lying around, together with open software solutions such as IFTTT, shows a level of innovation that many in the industry could learn from.”

Total solutions

While some people are interested in home automation, the majority cannot justify the cost. In Forrester's European Technographics Devices and Telecom Survey 2013, 31% of adults said they were interested in remote access to all the lights in their home, based on a survey of 12,567 people in Europe. The survey found 34% were interested in remote energy management, and 31% were interested in home security. On the other hand, almost half of those surveyed were not interested in having remote access to light control.

Home automation, such as the system developed by digitalSTROM, can be hugely expensive. Something as seemingly straightforward as switching on a light remotely can involve huge upfront costs in an integrated system.

In the report The Internet Of Things Comes Home, Bit By Bit, Forrester analyst Frank Gillett notes: “When a consumer simply needs to make sure that the lights are on or the door is locked, they see an integrated connected-home solution as dramatic overkill. Instead, as consumers add individual smart products to address additional problems, they will realise new tasks that this combination of gadgets could address – if only the solutions were able to communicate and interoperate.”

Gillett thinks consumers are more likely to buy lower-cost components, rather than a complete home automation system, to meet a particular need. The challenge is that these components will need to communicate in an open way and federated services will be needed to make them work together seamlessly, like an integrated system.