Making sense of the UK Cybersecurity Skills market.

There is much talk of cybersecurity skills shortages and there are many initiatives.

Most do not relate to the skills you most need to help protect your business, your supply chain and your customers.

How do you change that?

Summary

The current UK Cybersecurity Skills workforce can be summarised, using data from the Annual DCMS/DSIT Skills and Breaches reports[1], as follows:

- 110,000 Full time professionals, technicians and support staff:

- 36,000 with Service Providers to Government and Enterprise Customers

- 21,000 with Product Suppliers

- 12,000 in the Public Sector (including GCHQ/NCSC/MoD etc)

- 40,000 in 10,000 Private Sector Enterprises (over a thousand employees)

- Under 1,000 providing services to over a million SMEs (under 250 staff)

- 75,000 Part time professionals/technicians with other roles (e.g. anti-fraud/compliance)

- 65,000 with medium to large private sector employers

- 10,000 in the public sector

- 1,000,000 Responsible for cyber in SMEs etc. with little if any training/experience

Overall demand is growing at about 15 – 20% per annum, while public sector cybersecurity outsourcing spend is growing at 50% p.a. Meanwhile supply is growing at only about 10%.

The shortfall of professionals and technicians is over 50,000, increasing at over 10,000 p.a.

Meanwhile 700,000 businesses lack the skills to implement Cyber Essentials[2] . Only 400 cyber sector firms[3] provide training on how to use their own products and services and there are only 300 in the sector provide managed security services.

As with previous intra-UK digital skills crises (from the late 1960s through the subsequent waves of technology change to Y2K), spiralling staff turnover, in the face of rising skills shortages, can only be addressed by giving priority to selecting and cross-training mature entrants, including user staff, who have good reason for corporate loyalty. The cyber skills problem is, however, global. Trying to import skills or export jobs will not help.

Contents

- Digital Skills Shortages and Merry-Go-Rounds: Decimalisation to Y2K

- Past Action Plans: e.g. for the Y2K Skills Crisis

- The Cyber Skills Diagnosis – Pre-Covid, Pre-Ukraine

- What changed? What is now different?

- What skills do you need in-house and/or on tap?

- Todays Action Plans: including local/national cyber skills partnerships

-

Digital Skills Shortages and Merry-Go-Rounds: Decimalisation to Y2K

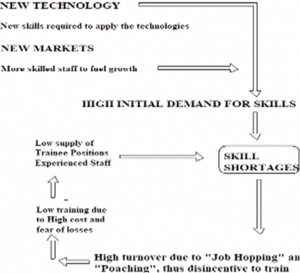

The causes of cyber skills shortages and the solutions are inherently no different to those for previous digital skills “crises”. The difference is that there is no obvious deadline, unlike the run-up to decimalisation (1970), to the financial services (“big bang” 1986) or Y2K (1996 -9).

The issues are akin to those that occurred with each wave of digital technology change until they were “cured” by the rise of outsourcing and offshoring, in the late 1990s, accelerating as users contracted out their Y2K problems. But the cyber skills shortages of today are global and many cannot be contracted out without putting the business as serious risk.

Instead of one national deadline we have individual deadlines, as sectors are hit by waves of attacks and survive or go down, according to their preparations, helped or hindered by the demands of regulators who may, or may not, know what they doing and why.

In the mid-1980s the “merry-go-round” pattern was identified and measured using the annual NCC salary and turnover surveys over previous years.

Not enough users took on trainees. This led to shortages of skilled and experienced staff in the areas of future growth. The problem was compounded by the low level of refresher and update training given to most of those already in the workforce. Employers who did not train their own staff, bid up the price for skilled staff in order to poach from those who do, whether to work as supposedly permanent staff or, more usually, as short stay contractors.

Individuals found it difficult to retrain and harder still to obtain the necessary practical experience to re-enter the workforce if they had been made redundant.

The resultant merry-go round meant that employers who had previously trained staff switched budgets into loyalty bonuses to retain staff and/or emergency recruitment.

Solutions were found. Then the 1991 recession “cured” the problem. The “solutions” were discontinued … until the next crisis … the run up to Y2K.

Those solutions required approaches to needs analysis, manpower planning, modular blended learning programmes and supervised work experience that few organisations today, outside large product and service providers, have the in-house skills to undertake.

The phenomenon can be seen and measured at its most acute whenever there is a short run demand to a finite timescale. The most recent example was the run up to GDPR.

The cyber skills situation escalated from “problem” to crisis” when Covid lockdown was followed by the Ukraine war and the rise of nation supported cybercrime as a service. It has no obvious deadline but most of the past action plans are relevant.

What is different to previous “crises” is that the pace of change has accelerated and the time scales for action are much shorter.

-

Past Action Plans: e.g. for the Y2K Skills Crisis

A comprehensive set of generic action plans (for Government, Suppliers and Users) to address the predicted Y2K Skills Crisis was assembled for the 1996 IT Skills Trends Report[4].

That report led, inter alia, to the Government funded Millennium Bugbusters Programme which gave intensive hands-on technical training to over 40,000 individuals on how to identify and fix problems in chip-controlled devices with two digit dates.

The recommendations for users included:

- Review your recruitment, training and retention strategies.

- Identify which skills are needed inhouse over what timescale.

- Start updating and reskilling the core team NOW.

- Integrate skills acquisition, development and retention.

- Manage the mobility of those you wish to recruit and retain,

- term contracts, projects bonuses and training contracts,

- local recruitment of those with family commitments and/or pastoral care needs.

- Challenge, interest and cherish those you wish to keep.

- Check your outsource suppliers have the skills they claim.

- Recognise the importance of continuity among front-line user support staff.

- Update those you wish to retain with the skills you need tomorrow as well as today.

A particular recommendation was the use of training contracts, requiring repayment of training costs to help reinforce loyalty among those whose earning capacity might be doubled or trebled after they had acquired new skills at your expense. This was accompanied by a warning that contracts, like loyalty, cut both ways, were not a panacea and needed to be reinforced by subsequent career paths and pastoral care to reduce the risk of poachers buying out the contract.

At least as important to ensuring staff retention and a return on developing the skills which others might wish to poach, was to look at the local recruitment of those with pastoral or family care needs for whom flexible working and tax efficient support packages were more important than nominal pay.

The section on diversity, including returner recruitment, included the value of looking at attracting, recruiting and updating/reskilling those wanting to return to full-time working after those for whom they had been caring moved into residential care or had died. This group could be especially valuable for key roles in emergency response teams where wide-ranging experience and people skills were at a premium.

Y2K was, however, over 20 years ago. It also accelerated the trend towards outsourcing which changed the nature of digital skills markets.

The current cybersecurity skills crisis is at least as great among those to whom to whom the problem has been outsourced as it is among the users. We need to recognise that, while needs overlap, the skills, aptitudes and attitudes sought by security vendors and outsourced service providers for response teams are significantly to those sought by user employers for the much smaller teams setting policy and negotiating linked outsource contracts, including for incident response. And for SMEs that is a part-time role for who-ever is in charge of digital as a whole … and even that may be a part-time role.

3 The Cyberskills Diagnosis: Pre-Covid, Pre-Ukraine

In 2020 DCMS studies of the Cyber Security skills pool[5] and Supply sector[6] summarised the UK Cyber Security recruitment pool as follows:

- 46,700 in core roles (professional/technical cyber-security job title) with Suppliers

- 11,800 in core roles in the public sector (GCHQ, MoD, Central/Local Govt, NHS etc.)

- 39,500 in core roles with private sector users, e.g. banks, defence, aerospace, retail etc.

- 8,700 in public sector roles that include cyber-responsibilities requiring recognised skills.

- 64,300 in private sector roles with cyber responsibilities requiring recognised skills.

- 1 million + with part-time cyber responsibilities and little by way of training/certification

It found an unsatisfied demand of about 30,000:

- 10,000 for core roles, plus demand for additional technical skills for those in post,

- 20,000 for those who had cyber as part of their responsibilities, with more focus on soft/people skills,

To that needed to be added about 17,000 p.a. to cover 12% growth and 4% attrition.

The studies found a supply pipeline of around 7,500 new entrants p.a.

- 2,000 from 3,360 cybersecurity graduates from 83 institutions,

- 2,000 from 30,886 computer science graduates from 128 institutions.

- 2,500 from current career conversion, re-training, or other routes:

- Students with relevant A Level/NVQ qualifications from HE/HEcourses.

- Retraining from other occupations, such as law enforcement

- Veterans from 15,000 leavers pa., 8,000 via the Career Transition Partnership

- MoD staff and military personnel including via the Defence Academy

- Transfers from other IT professional roles

- Alternative talent pools: neurodiverse groups, returners,rehabilitated offenders.

- 1,000 cyber-security apprenticeships (then 600 but doubling year on year).

The annual shortfall, to be added to the back log, was 10,000.

The result was an accelerating skills merry-go-round with geographic and sector hot spots in London, Thames Valley/Reading, Bath/Bristol and Manchester:

- 58% of ads for full-time “core” cyber professional roles and 51% for part-time “cyber enabled” roles requiring certificated skills also asked for 3 -5 years experience.

- 90% of job ads for “core” roles and 78% for “enabled” roles asked for graduates.

- Jobs ads for cyber staff with 3 – 5 years experience offered a 29% premium over those for mainstream IT staff with equivalent experience.

- But new graduates were being offered less for cyber training roles than for mainstream IT roles. In consequence many cybersecurity graduates did not go into cyber security jobs and few with other digital degrees did so.

- Meanwhile most large users outsourced some or all of their cybersecurity. Many fewer SMEs did so and few cyber outsource suppliers offered affordable services to SMEs.

- None of the reports mentioned the need to check credentials for fraudulent claims of competence or experience, let alone to vet candidates for probity.

Recommendation to SASIG members on how to handle the consequences included:

- Review the salaries you offer to Cybersecurity and Computer Science Graduates: unless you really were wedded to security by design as opposed to by afterthought and the absence of a premium for those going into response roles was deliberate.

- Trawl for talent among those who understand the business: whether your own users or those of your customers if you are a cyber sector supplier.

- Use the Cyber Resilience Centre programmes (e.g. Cyber PATH) to upgrade existing staff, “try before you buy” those on local training programmes and to secure your SME supply and distribution chains.

- Use wider work experience programmes with schools, colleges, universities and cyberhubs (or similar) to “try before you buy” with regard to your own recruitment and organising affordable virtual CISO support for SMEs.

Then came Covid followed by the Ukraine War.

4 What changed? What is now different?

Most of the world, including criminals went on-line during Covid. So too, did most of education, entertainment, recruitment and training. This opened up massive opportunities for fraud and abuse, leaving the cyber security industry and its customers playing catch up.

The increased scale and nature of on-line crime during Covid lockdown and afterwards is unclear, but surveys of user experience, such as that from Ofcom, indicate that most of us now routinely experience on-line fraud and have contacted our bank or internet service provider. How much or little of that got reported to law enforcement is another matter.

By 2023 according to the Ofcom On-line scams and fraud report[7]

- 51% of UK adults have experienced impersonation fraud

- 42% counterfeit goods

- 40% investment, pension, ponzi etc

- 37% software, service, ransomware etc

- 30% fake employment

- 29% romance.

Then came the mobilisation of the UK and US cyber reservists during the build up to the Russian invasion of the Ukraine. This added a stress factor to the skills market while UK Government spend on cyber security outsourcing to help protect its own systems rose by over 40% in single year. It has since been growing at 50% compound per annum.

Those outsourcing contracts helped underpinned a massive expansion of the training programmes of the 20 or so dominant suppliers who account for most of the UK private sector cyber professional work force.

But the expansion in demand for technical and professional cyber skills was even greater.

The skills gap measured by the DCMS reports[8] widened further.

- The proportion of new entrants in the cyber sector rose from 12% in 2020 to 18% in 2022 but the volume of job adverts rose by 58%.

- The annual shortfall in the technical/professional pipeline increased to 14,000.

- 73% of Cyber Sector employers provide training but

- under 20% joined their employer as first entrants

- 30% transferred in from a non-cyber role

- 50% previously worked in a cyber role elsewhere.

- Barely 20% of Cyber employers outside the supply sector provide any training, 85% have it as part of a portfolio of task and transitioned from a non-cyber role

- Outside the cyber sector 50% have only one employee responsible for cyber. Even in medium to large businesses the median team is 2 – 3. Only 20% of medium businesses and 23% of large have 4 -5 or more.

- Only 32% of cyber sector employers have more than 10 staff

The good news is the recruitment expectations in the UK are now marginally less unrealistic than those in other Western nations. According to OECD Data[9] the other 5 Eyes Nations (Canada, Australia and New Zealand) are even more reluctant to take on trainees and the EU is little better, save for Eastern Europe. UK demand for at least three years experience on the part of recruits is down to 50%, compared to 70% in the US.

Three quarters of cyber sector employers now offer training but barely a fifth of their staff joined as trainees, half were poached from elsewhere. The balance transferred in from a non-cyber role.

Meanwhile, outside the cyber sector, barely a fifth of employers offer training to those in charge of cyber. 85% of those looking after cyber for users, as opposed those working with cyber sector supplier, have cyber as part of a wider role. And most are working in teams too small to organise in-house training or supervised work experience.

Meanwhile the problems with recruitment fraud, (whether fraudulent job ads designed to harvest the credentials of applicants or fraudsters seeking to infiltrate employers) have soared as organised crime (including that linked to nation state actors seeking to fund their own operations in the face of Western sanctions) has changed its business models. We can therefore see the rise of Cybercrime as a Service, as indicated in the most recent report from Microsoft: Cyber Signals: Shifting tactics show surge in business email compromise

-

What skills do you need in-house and/or on tap?

DCMS data[10] indicates that 60% of medium to large employers, and a similar proportion of all those in Financial Services and the Public Sector are outsourcing some or all of the cybersecurity. But the proportion drops sharply, to under 17% among the SMEs least likely to have any in-house skills to start with.

The data also indicates that only those providing cyber or information and communications services to others, in financial services or otherwise large enough to be able to organise outsourcing are likely to have done a needs analysis. Most of the needs analyses done by user appear to have been organised as part of the process of agreeing an outsourcing contract or to meet the requirements of cyber insurance policies – now that cyber is routinely being excluded from mainstream business continuity policies

Most large user organisations now outsource many or all of the technical roles, leaving a small in-house team whose prime need is the skills to manage the interfaces between their outsource providers, user departments. compliance officers, auditors, insurers and board.

When needs analyses are done, other than by large cyber employers, the main obstacle to training delivery is nearly always the time of those to be trained and most delivery is self-guided downloads from on-line libraries.

The vulnerable SMEs in your supply chain, who are least likely to have any in-house technical skills, are also least likely to have done an analysis of what they need, least likely to be willing to pay for professional mentoring to help them do so and least likely to have a budget that is attractive to an outsource provider.

They are the community that the Cyber Resilience Centres are expected to assist, including by using supervised work experience students, mainly on NCSC certified courses, via the Cyber PATH programme.

The concept of using work experience students to support SMEs is excellent. The Cyberhubs are another good example. But the model will only work to scale if many more employers participate, using such programmes as part of their own skills pipeline and efforts to support the SMEs in their own supply chains.

-

Action plans including local/national cyber skills partnerships

Current national cybersecurity skills programmes will not produce results on the scale needed for several years. They are, in any case, focussed on the needs of those who plan and pay for them. Unless you are large enough to already be engaged directly, feeding in requirements from your own needs analysis and talent acquisition/development programmes, you need to join partnerships that will build reliable access to the skills you need, when and where you need them, whether in house or tap.

You also need to work with your peers to ensure your needs are reflected in skills policy and deliver at all levels, from national groups (like the Cyber Security Council or Tech Skills) to those working on locally cyber skills inputs to the Local Skills Improvement Plans and STEM Hubs. That means JOINING a local or sector co-operative to share the task of getting your voice heard alongside over the voices which currently dominate policy discussion.

What skills do you need that are not being covered already?

For most employers outside the cybersecurity sector itself the Cyber Security Generalists work stream of the UK Cybersecurity Council is the most relevant national partnership. However, its current focus on Cybok instead of NIST (more likely to be used by Financial Services employers) limits its relevance to those more concerned with demands of Financial Services Regulators or the Global payments industry (e.g PCI-DSS) than with NCSC guidance.

The best way of addressing that limitation is for more many employers to not only join the Cyber Security Council and be active on its existing working groups but also to help resource a broader range of activities. The current priorities do not include identity and access management skills, let alone assessing competence to the use the credentials checking and personal vetting and monitoring tools and services, that need to be deployed to reduce the risk of impersonation as nation state actors exploit the revenue potential of “cyber-crime as a service” .

The team looking at Cyber Skills for London on behalf of the London Cyber Resilience Centre Advisory Group is assembling a project to pilot the agreement of accreditable micro-modules. Subject to support from those wishing to use the micro-modules to upgrade the skills of their own staff they aim to begin with those in this area, building on the insider risk mitigation guidance available from the National Protective Security Authority (people) as well as the technical material from NCSC and the training programmes and vetting services organised by organisation like CIFAS and some of the Identity Service Providers

The Advisory Group of the London Cyber Resilience Centre, which I convene, is already in discussion with CIFAS and OCN London and looking for support from vendors who want training on how to use their automated tools embedded into publicly funded training programmes, as well as included in the libraries of on-line modules being used for the in-house updating programmes run by commercial training providers like QA.

There is, however, also a serious disconnect between the diversity of skills and talents that cybersecurity employers (from Vendors and Support operations to user CISOs) say they want and the wording in the job adverts agreed between their personnel departments and most recruitment agencies.

DCMS and DfE have followed the main US-based technical professional bodies (e.g. Comptia and ISC2) in commissioning analyses of demand for cyber security skills from Burning Glass (which uses the US O*NET job definitions). The Security section of SFIA (now the main global digital skills framework) maps onto the US definitions but allows for considerably more detail. Meanwhile while UK recruitment agencies are more likely to use more nuanced analyses (based on the wording job ads) from Vacancysoft to pick up local and hybrid demand. And most of the demand from user organisations is for hybrid skills sets which vary according to the sector(e.g. Financial Services, Construction, Health etc.).

If you are providing security for a regulated employer (e.g. Financial Services or Health Care) you should use the Better Hiring Institute Blueprint to improve your own recruitment processes and get your HR team to join the relevant BHI sector working group to improve theirs. You should also help set up the missing group that is needed to develop the recruitment standards we do not yet have for Cyber Security itself. Can you afford to wait for Godot while fraudsters infiltrate your organisation and its supply chain? If not …l

How do you help retain your key staff and recruit/train those likely to stay with you?

The recommendations in section 2 (above) for the Digital Skills during run up to Y2K and in Section 3 (above) for Cyber Skills before Covid, hold good but the 2022 DCMS cyber security sectoral analysis[11] found twice as many suppliers offering accreditation services (GDPR, ISO 27001, Cyber Essentials etc) as offered training or services help to meet those standards.

If you are not in a position to organise your own in-house training, supervised work experience and pastoral care programmes you need to work in partnership with your peers, locally as well as nationally, to create self-help networks. You should encourage and support staff interested in participating in such networks as volunteers with incentives (not necessarily cash) to use them to help identify those who you might wish to recruit.

Examples include:

- The Local STEM Hubs working in collaboration with Careers Hubs run by the Careers and Enterprise Company. These reach almost all local schools, as opposed to the 2% reached by current cyber programmes but they need extending to cover mature entrants. You should look at how to help them do so locally

- The CRC CYBER PATH work experience programmes. In London we aim use this as a part of a much more powerful Cyber Skills for London programme based on City University and a network of partners to meet high level global cyber skills needs as well as the local needs of London’s half a million or so small firms and micro-businesses.

- Local Cyberhub experiential learning, work experience and SOC operations. I attended the launch of the pilot (run by Bluescreen IT, now part of BIT Group) on which these are based, in Plymouth, five years ago and have blogged on progress over the years.

The Cyberhub concept is simple, trainees supervised from a variety of programmes and backgrounds gain experience by running a shared Security Operations Centre for local Businesses. But success depends on support from employers who want to use the Cyberhub to train their own staff, identify recruits from it to hire for themselves and/or buy services via the hub if they feel unable to employ, support and supervise them in-house.

- Diversity, mentoring and pastoral care support groups can greatly help employers who lack the in-house resources to arrange their own advice, guidance and support, including the clinical, education and wellbeing support as is often necessary for diverse talent.

Most are run by enthusiasts who are too busy to discover who else is seeking to address the same problems. Supporting staff who are interested in helping organise, not just participate, is an excellent motivator as well as helping handle your own pastoral care issues. It will also help identify those more interested in staying with an employer who helps meet their lifestyle and family needs than in the next challenge or pay rise.

- Those interested in working together at the policy level should join the “Security skills and Partnership sub-group” of the 21st Century Skills Working Group of the Digital Policy Alliance and help join the dots across the many groups that confuse where they should inform.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-skills-in-the-uk-labour-market-2021

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/understanding-the-cyber-security-recruitment-pool

DCMS Cybersecurity Longitudinal Survey

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-skills-in-the-uk-labour-market-2022

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-sectoral-analysis-2020

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-sectoral-analysis-2022

[4] The End is Nigh: 1996 IT Skills Trends Report; Produced for IDPM and the Computer Weekly 500 Club. Electronic copies available from the Winsafe on-line archive. E-mail [email protected] for details.

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/understanding-the-cyber-security-recruitment-pool

[6] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-sectoral-analysis-2020

[7]https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/255409/online-scams-and-fraud-summary-report.pdf

[8] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-skills-in-the-uk-labour-market-2022

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-sectoral-analysis-2022

[9]https://www.oecd.org/unitedkingdom/building-a-skilled-cyber-security-workforce-in-five-countries-5fd44e6c-en.htm

[10] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-skills-in-the-uk-labour-market-2022

[11] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-sectoral-analysis-2022