Gov dodged scrutiny of Universal Credit

The damage coalition cuts and bodge have done to Universal Credit was omitted from the National Audit Office assessment of the scheme in November.

The damage coalition cuts and bodge have done to Universal Credit was omitted from the National Audit Office assessment of the scheme in November.

The full story emerged a week after the auditor published its report. Had the NAO been able to put all the cards on the table, it may have discredited the coalition as the country entered its few months of mudslinging before the general election in May.

The ambitious Universal Credit welfare scheme was in a worse state than the Department for Work and Pensions had admitted when the auditor did its assessment. But this may have been caused more by government cuts in welfare to people in low paid jobs than its well-publicised IT problems.

The NAO assessment was incomplete because DWP had not disclosed the latest estimates the NAO used to determine if the programme’s ongoing development was financially viable.

Those numbers would be drawn from the 2014 Universal Credit business case, which the Treasury signed off in September.

“The department did not fully revise the Autumn 2014 figures,” said the NAO report on 26 November.

The shape of those figures became apparent just a week later when chancellor George Osborne made his budget statement, on 3 December.

He unveiled numbers the public auditor had not been allowed to publish: further cuts to the amount of income support Universal Credit would deliver.

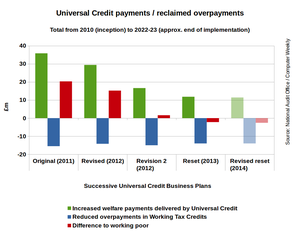

This and three other revisions the chancellor and the DWP had made to their flagship scheme’s business plan since 2011 had diminished its potency drastically.

This and three other revisions the chancellor and the DWP had made to their flagship scheme’s business plan since 2011 had diminished its potency drastically.

The chancellor’s cuts had been a primary factor in the NAO’s assessment of the programme’s diminishing success.

But there was worse to come. The scheme had also been undermined by problems the DWP and Cabinet Office had (overseen by the Treasury) with the IT system.

Those problems postponed the time when people could start receiving Universal Credit. The auditor’s second primary measure of the scheme’s success was the total amount of such payments administered in the first twelve years since work and pensions secretary Iain Duncan Smith commenced construction on Universal Credit in 2010.

By these two measures, Universal Credit’s potency had diminished by two-thirds since 2010 – a £24bn fall. It would deliver just £11.8bn of help in its first twelve years, by the most recent available numbers. That was less than the cost to build it.

The NAO said Universal Credit’s potency would shrink another £2.3bn if it was delayed even by another six months.

Lo and behold, while the chancellor was delivering his statement on 3 December, the Office for Budget Responsibility issued a forecast that Universal Credit’s development would indeed slip another six months.

With ongoing IT problems, the NAO had raised the possibility that it might even be delayed another year. Along with the chancellor’s further cuts, the original £35.8bn advantage in doing Universal Credit was diminishing to almost nothing.

More cuts than IT

The NAO and Institute for Fiscal Studies have now hinged their final judgement on Universal Credit’s success on how the implementation overcomes its IT problems.

But the NAO based its judgement on misleading calculations. A further delay would obviously lessen the amount of social security payments it administered in the twelve years that followed the day Iain Duncan Smith announced his intention to do it. That’s how the NAO predicted Universal Credit would lose £2.3bn of its value if it was delayed another six months. It reckoned Universal Credit was worth less while it was unfinished.

By the same reckoning, if Smith had put his announcement off for a single day in 2010, perhaps to savour his moment in destiny, it would have cost Universal Credit £12m in benefits not delivered: not delivered that is, until they were delivered, a day later than originally planned.

It judged the scheme by a measure that could be meaningful only once it was finished.

The final reckoning wouldn’t be whether the system was finished. It would be how much social security it delivered, how well, and with what difference to society and the poor.

The coalition’s own welfare cuts undermined Universal Credit more than its IT delays.

More damage

Yet it will cause alarm when Universal Credit’s further IT-related delays emerge officially, as they will undoubtedly continue to do after the election when the almighty bodge the coalition made of its development bears fruit. Politicians of any creed would exploit this to damage their opponents at the expense of the programme. Even the Conservatives who conceived the scheme would benefit from its collapse, and the damage it would do to big government and welfare, both of which they have vowed to diminish. The purpose of the venture, then long-forgotten, would sink under the waves with the system itself, and probably its captain.