Stuart Monk - Fotolia

How emails sent to and from Parliament are monitored

Government officials deny that emails sent by MPs are open to surveillance by GCHQ and NSA - we examine the evidence

Last week, Computer Weekly reported that Parliamentary emails and documents stored in the cloud were open to scanning and surveillance by US and British intelligence agencies. GCHQ, the Cabinet Office, and the Parliamentary Digital Service have each claimed that the report was "wrong" or "inaccurate", but have not yet substantiated any specific alleged error or inaccuracy.

Members of the House of Commons and House of Lords have said they intend to raise questions when Parliament starts sitting this week. Here, we set out the documentary evidence of email monitoring, including from highly classified GCHQ and NSA documents released by Edward Snowden.

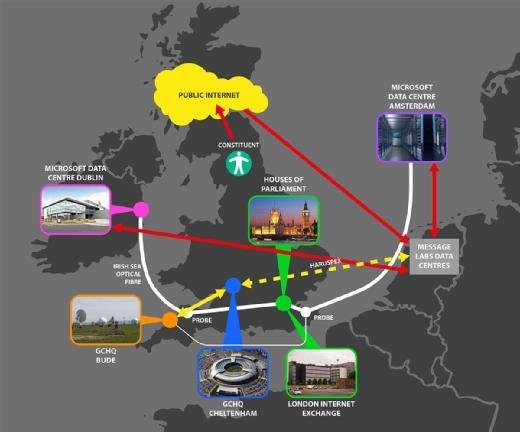

Every time an email goes to or from an MP at parliament.uk, the email domain used by MPs, peers and their staff, it is intercepted and scanned in overseas datacentres run by MessageLabs, a subsidiary of the US corporation Symantec. As it passes overseas, it automatically passes through fibre-optic cables tapped by GCHQ, through a collection system known as Tempora.

"Full take" of every message and its contents is then available to analysts from any cable "on cover" - meaning that one of GCHQ's collection of available probes has been connected to the optical fibre of interest, intercepting data at the rate of 10Gbps.

Parliamentary data held in Microsoft datacentres can also be available to the US National Security Agency (NSA) because of secret US government directions to provide access, made under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Amendment Act of 2008. Microsoft, which provides Parliament with its cloud-based Office 365 Enterprise service from datacentres in Amsterdam, Dublin and London, is prohibited under US law from revealing the surveillance service it is required to provide, which was exposed by the Guardian in 2013.

The scanning of all parliamentary email is not and cannot be concealed. Over the past six weeks, Computer Weekly has on five occasions asked the director of the Parliamentary Digital Service (PDS), Rob Greig, for an interview or for responses to detailed questions about the security of parliamentary emails and documents. The House of Commons communications office initially said: "The UK Parliament does not use the services you refer to".

After publication of our original article last week, the House of Commons communications office claimed that it "did not have the opportunity to respond in advance" to the report. Greig said, "The claims made in this article are inaccurate, misleading and irresponsible. The emails and documents of Members and staff of Parliament are private and all data in transit to the Microsoft datacentres is secured with a very high level of encryption designed to prevent data interception".

In fact, every email sent from Parliament has an automatic statement inserted at the end stating, "This email address is not secure, is not encrypted and should not be used for sensitive data." The same statement has also appeared on every email sent to Computer Weekly by the communications office.

Despite this, in a further statement issued to Computer Weekly for this article, Greig claimed that end-to-end encryption is in place for parliamentary emails "while they are in our infrastructure".

He said: “All parliamentary emails are private and are strongly encrypted end-to-end while they are in our infrastructure. Like all responsible organisations we take cyber security and information security extremely seriously. We regularly review and respond to evolving threats to ensure the integrity of the parliamentary network."

Computer Weekly has asked the House of Commons communications office to explain how its claims can be reconciled with the statement placed on all outgoing email, but has not received a reply specific to that question.

Members of both Houses say they intend to ask who in Parliament gave consent for parliamentary emails to be intercepted and scanned, and which government agencies have access to the controls of the email scanning system.

In a further message, the communications office said that Microsoft SkyDrive is a "service we do not use". But a Parliamentary Administration Committee report in November 2013, before Greig was appointed, says that as part of Office 365, "Skydrive Pro will allow documents to be shared and accessed on mobile devices”. Greig added. "In 2013 we deployed OneDrive for Business which features enterprise grade security, not the SkyDrive (now OneDrive) service."

According to Microsoft, in 2014 SkyDrive was updated to OneDrive. OneDrive for Business is an upgraded version of OneDrive, and the updated name for SkyDrive Pro.

In a 2013 statement to the Guardian about NSA and Prism access to its services, Microsoft said: "When we upgrade or update products legal obligations may in some circumstances require that we maintain the ability to provide information in response to a law enforcement or national security request."

How NSA worked with Microsoft to get inside Office 365 Enterprise

Subsequent NSA documents revealed by Edward Snowden revealed OneDrive was connected to the Prism surveillance system.

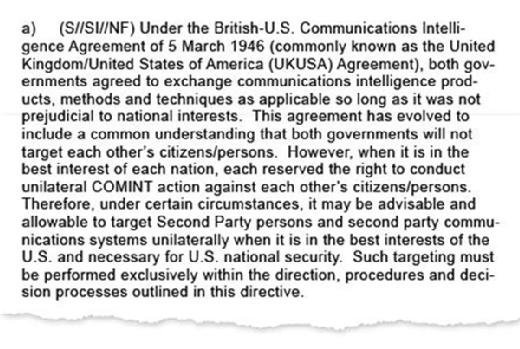

Prism was developed to exploit what NSA calls the "home field advantage" of having most of the world's large IT companies based in the US. In 2008, Congress passed the FISA Amendments Act (FAA) to enlarge the scale of NSA global surveillance and to retrospectively legalise unconstitutional internet domestic surveillance programmes begun in 2001. Section 702 of FAA (FAA 702) specifies "Procedures for targeting certain persons outside the United States other than United States persons”.

Under US law, there are no restrictions on what NSA analysts can take from the Prism system and pass to other intelligence agencies, provided the targets are foreign persons or companies outside the US. Foreign governments are a primary target, despite the US-UK special relationship. NSA documents confirm that the US targets friendly "second party" countries like Britain "when it is in the best interests of the US and necessary for US national security".

Because of the secret power of FAA 702, at the same time Microsoft was negotiating its contact with Parliament in 2012, documents from Edward Snowden released after the original Guardian revelations show, Microsoft was also arranging for the system it was selling Parliament, then called SkyDrive, to be connected to Prism for foreign intelligence surveillance purposes. At the same time, Microsoft was also working with the FBI to defeat the updated SSL encryption system it was offering Parliament as part of the Outlook email programs contained within the Office 365 Enterprise system.

According to an NSA information bulletin published in December 2012 and available to all NSA staff, on 31 July 2012 Microsoft gave NSA analysts a sudden headache by starting to encrypt the "new Outlook.com service. This ... encryption effectively cut off collection of the new service for FAA 702 ... for the Intelligence Community", NSA warned staff.

Microsoft then broke the new system, on legal orders. The NSA report states that Microsoft, "working with the FBI, developed a surveillance capability to deal with the new SSL. These solutions were successfully tested and went live on 12 December 2012". The report concluded that after defeating encryption protection on Outlook.com, "an increase in collection volume as a result of this solution has already been noted".

On 7 March 2013, another NSA information bulletin document released by Edward Snowden proclaimed the "highlight" that Microsoft's SkyDrive system had been opened up to full NSA inspection, including for Word, PowerPoint, and Excel files. The document, classified "Top Secret - No foreign dissemination", was headlined "Microsoft SkyDrive collection now part of Prism standard stored communications collection".

"Beginning on 7 March 2013, Prism now collects Microsoft SkyDrive data as part of its standard Store Communications collection package for a tasked FISA Amendments Act Section 702 (FAA702) selector," it continued. "This new capability will result in a much more complete and timely collection response ... for our Enterprise customers."

In a further statement issued to Computer Weekly for this article, a House of Commons spokesperson said: "Parliament has used, and continues to use, OneDrive for Business. While this was previously called SkyDrive Pro, it is an entirely different service from the consumer service that you refer to that happens to share similar branding. Parliament has not adopted a consumer service but rather an enterprise grade service with all the legal protections and accreditations that entails."

Even if MPs did not know that the new computer systems they were to get in 2015 would be supplied open to NSA inspection, the UK intelligence agency GCHQ already knew what Prism could do - and wanted in. On 30 April 2013, GCHQ chief Sir Iain Lobban made a two-day visit to NSA's Fort Meade headquarters, meeting with his NSA counterpart General Keith Alexander.

NSA's Foreign Affairs briefing note for the trip, leaked by Edward Snowden, revealed that "unsupervised access to FAA 702 data ... remains on GCHQ’s wish list and is something its leadership still desires. NSA and SID leadership are well aware of GCHQ’s request for this data".

Another newsletter entry stated that NSA already had pre-encryption access to Outlook email. "For Prism collection against Hotmail, Live, and Outlook.com, emails will be unaffected because Prism collects this data prior to encryption."

How email metadata is collected under GCHQ’s Tempora

Parliament’s decision to move to the enterprise cloud version of Microsoft Office in 2014, means that every email every MP or peer now sends or receives, and every file they or their staff work on in shared cloud storage, has become open to comprehensive and simple surveillance that would not have been possible if the data had been kept in Britain.

Sending Parliament's data across optical fibre cables to the Netherlands and Ireland – where Microsoft has its datacentres - means that the emails and files are automatically collected by GCHQ's bulk interception system, Tempora, which is listed in secret documents as having "probes" on commercial cables crossing the Irish Sea and English Channel.

Under existing law, GCHQ automatically stores details of the senders, recipients and headings of all emails accessed going in and out of the UK, permitting access to UK metadata without restrictions.

For over 40 years, MPs’ communications have been partially protected from interception by the so-called “Wilson doctrine”, a policy proclaimed by the former prime minister Harold Wilson in 1968 and maintained by his successors. The policy now includes email. But the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) has ruled that the "Wilson doctrine applies only to targeted, and not incidental, interception of Parliamentary communications", and that it "has no legal effect."

The government has refused to extend the Wilson doctrine to bulk interception, claiming that data is moving “too fast”. Experts say this claim is absurd, as GCHQ sorts petabytes of optical fibre data every hour. But the combined effect of the policy and the Office 365 cloud decision is that MPs’ emails can now be automatically intercepted, in bulk, and without special protection.

How parliamentary emails are scanned

The first diagram, below, shows how, when a constituent communicates to an MP, the email is routed. It is sent from the constituent's computer and internet provider to and through a network run by the US-owned company MessageLabs for spam and malware scanning. It is then passed to email servers run by Microsoft's Outlook.com service. From there, it is passed to the Parliamentary Digital Service (PDS) in Westminster, and to the receiving MP. MPs’ outgoing emails follow the same path, in reverse.

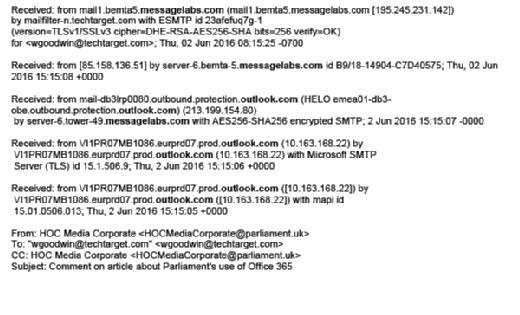

The path of every email in and out of parliament.uk is recorded in "headers" sent within every email, as shown in the illustration below. These include both MessageLabs and Microsoft email servers at overseas datacentres.

The central and essential role of MessageLabs computers in handling parliamentary email is confirmed by the public Internet Mail Exchange (MX) record for parliament.uk, registered with the Internet Domain Name System (DNS).

Every MX record is specified by the domain owner (in this case, parliament.uk), and specifies the server or servers responsible for accepting email messages. DNS and MX record lookup services are freely available to use on the internet.

As of 2 June 2016, the MX record for parliament.uk mail directed all incoming email to one of four MessageLabs datacentres, as shown above. Two are in France, one in Germany, and the other in the UK. The use of multiple datacentres allows for load sharing and balancing in handling messages. Two reserve datacentres are also listed.

In order to block malware, viruses or cyber attacks, the email messages have to be unencrypted so that their content can be scanned and recognised. This places the MessageLabs system serving Parliament in a key cyber defence role, and explains why it is connected to GCHQ and of interest to MI5.

Many businesses, and the rest of the UK government, use Symantec's Email Security.cloud service, incorporating MessageLabs scanners, to filter email messages. According to Symantec's data sheet, "The service analyses multiple email components including email body, subject, and headers, as well as text within Microsoft Office documents and PDFs that are embedded within emails or sent as attachments."

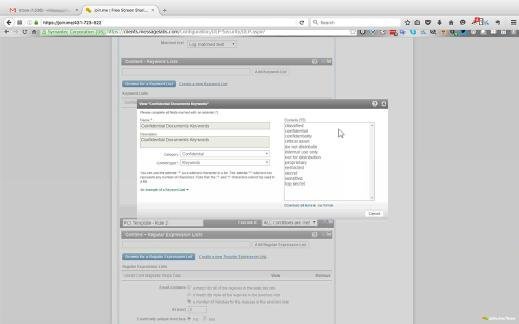

Computer Weekly has obtained copies of published user manuals for the Symantec Email Security.cloud service, and screenshots from the management console of a live installation. The first screenshot below shows how MessageLabs can use "keywords" automatically to scan for confidential or secret information being passed by email.

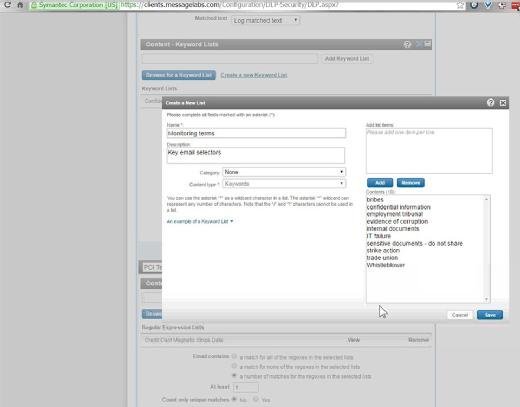

The second screenshot below shows how new checks can be added by controllers, using lists of search terms or "regular expressions".

Interception without a warrant for monitoring is legal, provided the "controller of the telecommunications system on which they are effected has made all reasonable efforts to inform potential users that interceptions may be made", according to the Lawful Business Practice Regulations.

According to the government's recently published new Code of Practice for Interception, "Regulations permit the government to protect national security, for example to test and assure the security of their own systems from cyberattack. They can also be used by the private sector for a broad range of business purposes, including the monitoring of productivity and the detection of offences by employees. The communications systems in question are private networks which the organisation concerned (whether that is a public or private body) has the right to control, and the regulations recognise that an interception warrant is not needed when the information being gathered from the network meets the criteria set out in the regulations.”

"The requirement for consent from system controllers ensures that companies are fully aware that their networks are being monitored in the interests of national security,” the Code of Practice notes.

Parliamentary Digital Service director Rob Greig said: “Parliament takes its duties very seriously in relation to this issue and complies with them in all cases.”

Ancient entrail interpreter protects Britain

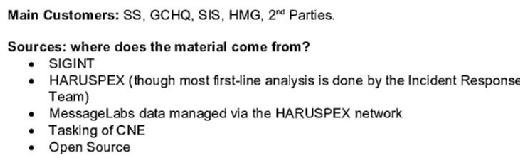

The official purpose of scanning MPs' email is to block spam and malware from getting in or out of Parliament. But GCHQ documents, classified above "Top Secret", reveal that the agency receives and analyses "MessageLabs data managed via the Haruspex network".

Historically, a Haruspex was a Roman temple official who interpreted signs and warned of omens, based on examining entrails from sacrificed animals.

GCHQ's Haruspex network is primarily part of Britain's cyber defence system, sifting communications for evidence of "intrusion analysis" and "electronic attack". But according to classified documents, the purposes for which GCHQ can use network monitoring information obtained "by consent" has secretly been enlarged beyond "the detection, analysis and prevention of network-based attacks against HM government computer systems".

According to GCHQ's standing instructions on "Cyber Defence Operation Legal and Policy": "Advice has already been given that some activities which do not constitute network-based attack may be reported from Haruspex, provided that to do so is in the interests of national security".

Responding to last week’s Computer Weekly article, GCHQ and the Cabinet Office said, "The suggestion that GCHQ routinely collects and reads the emails of parliamentarians is simply wrong." They did not deny that parliamentary email data was collected by GCHQ, that parliamentary emails were scanned, nor that GCHQ had access to the MessageLabs scanning system.

The Cabinet Office added, "The Wilson doctrine, which strictly controls any access to parliamentarians communications, applies in full to GCHQ." Prime minister David Cameron has said that the Wilson doctrine does not apply to bulk collection by GCHQ. Nor does it apply to the interception of email by the MessageLabs system, which is claimed to operate with the consent of MPs and peers.

The Cabinet Office also said, "The UK's intelligence and security agencies operate under one of the strictest legal regimes in the world with oversight from independent commissioners and Parliament itself through the Intelligence and Security Committee."

Rob Greig, director of the Parliamentary Digital Service, has also said, "Like all responsible organisations we take cyber security and information security extremely seriously. We regularly review and respond to evolving threats to ensure the integrity of the parliamentary network."

GCHQ was approached for further comment on this article, but the agency said it had nothing to add.

Serjeant at Arms resigned over "security risk" to MPs' email

Controversy still surrounds the pre-announced resignation two months ago of long-serving MI5 official Paul Martin, who was appointed Parliament's first security director in 2013, and given responsibility for cyber security. Martin, who will stand down this September, was accused last year by friends of the former Commons' Serjeant at Arms, Lawrence Ward (pictured), of placing MPs under surveillance. Ward then resigned, after serving for three years.

Serjeant at Arms Lawrence Ward, who resigned in 2014 because of security concerns. Photo: House of Commons

Serjeant at Arms Lawrence Ward, who resigned in 2014 because of security concerns. Photo: House of Commons

'Lawrence was angry about the apparently untrammelled power being given to Mr Martin", the Daily Mail reported. "Instead of protecting MPs, Mr Martin seems to think the MPs are the ones presenting the threat."

"The House has to decide whether it wants to continue to manage its own security or whether it hands that over to the state via an agent who, while employed by Parliament, remains a pass-holding member of the security services", the source added.

Commenting on Ward's sudden resignation, Labour MP Keith Vaz, who formerly chaired the Home Affairs Committee, said: "'If people are in a position where they are reading MPs' emails, we should be told. Many people come to MPs in confidence and there's no point having 'this email is confidential' on the bottom of our messages if anyone can read them."